Illustration by Rebecca Sampson

Meet an icon: The man who designed our ’Shoe

Dedicated to the university and inspired by Europe’s ancient landmarks, 1907 graduate Howard Dwight Smith created Ohio Stadium, an architectural marvel that has served for 100 years.

Illustration by Rebecca Sampson

By Tom Reed

The stone marker sits beside an overgrown shrub in Section 87 of Columbus’ Green Lawn Cemetery. Its bronze plaque bears only Howard Dwight Smith’s name and the dates his life spanned: February 21, 1886, to April 27, 1958.

There is no posh headstone or obelisk to commemorate the architect and Ohio State alumnus buried here. The final resting place of the man who designed mansions for millionaires and an iconic football stadium for Ohio State is in keeping with how he lived. Smith valued modesty; it was his unshakable foundation.

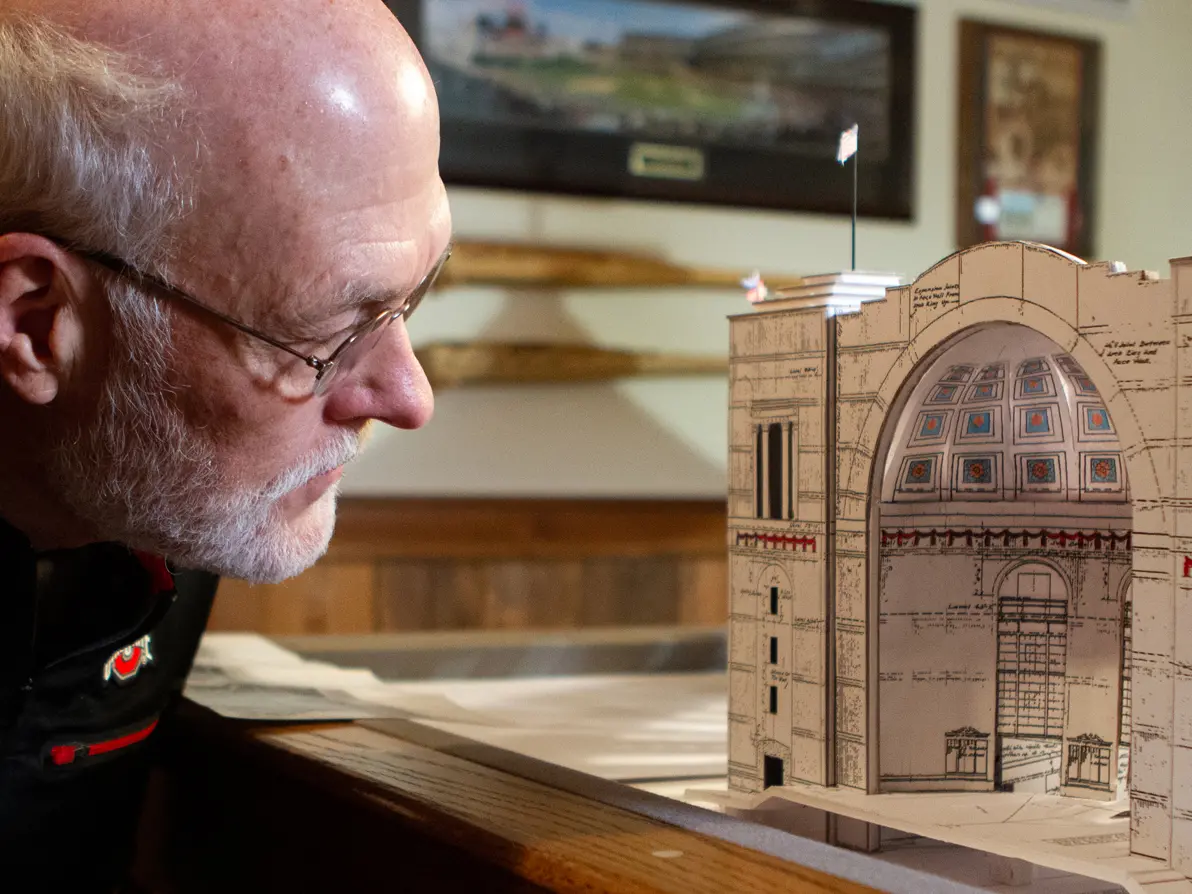

“Humility was important to Howard Dwight Smith, in himself and in those who served the university,” says Jamie Greene ’84, architect and founder of Columbus-based Planning NEXT. “According to his son-in-law Gene [D’Angelo], Howard Dwight Smith would not allow architects to put their names on signs where construction was happening. He didn’t think it was necessary. Let the work speak for itself.”

Greene is well-versed in the legacy of Smith, a prolific architect who designed more than 30 Ohio State structures and additional local landmarks from 1918 to 1956, the most active years of his career. He believes Smith’s gravestone epitomizes a man who constructed monuments to others while choosing a modest life himself.

“My fondness for Howard Dwight Smith lies at the intersection of his incredible contributions to the built environment of Central Ohio and his profound humility,” Greene says. “Green Lawn Cemetery is known for large and, in some cases, elaborate markers and mausoleums honoring city leaders. Howard Dwight Smith designed his own marker. It is about 3 feet wide and barely protrudes from the ground.”

In contrast, the project for which he is best known could be seen as audacious. Borrowing from the architectural wonders that captivated him in Europe and planning for 63,000 fans, Smith transformed the art of stadium building.

His horseshoe-shaped stadium was dubbed “The House that Harley Built” in recognition of All-American Chic Harley, whose prodigious talent brought renown to the university’s football program and drew overflow crowds to Ohio Field that elevated the need for a new venue. And while President William Oxley Thompson and Thomas French, president of the Athletic Board, are seen as the visionaries behind Ohio Stadium, and Director of Athletics Lynn St. John as the vanguard of a growing sports program, it was Smith who had the nous and fortitude to give shape to their aspirations.

While many consider the ’Shoe Smith’s most glittering accomplishment — it earned him a 1921 gold medal for public building design from the American Institute of Architects — admirers hope the centennial will shed light on his other projects and the altruism that ran through all of his work.

A professor of architecture, a mentor, an administrator, a father of five — Smith was all of these. So, too, was he a resourceful designer who could conceive a dream home for a burgeoning college football program, an open-air school for children at risk of tuberculosis and a welcoming neighborhood for less fortunate people in his city.

“He has to be considered one of the most versatile architects of his time,” Greene says. “He designed all these different types of structures, and he did them well. He was a capable, humble guy who did amazing things without fanfare.”

Over the course of an hourlong conversation, actress Beverly D’Angelo calls Smith “Grandpa” just twice. Almost every other reference is to “Howard Dwight Smith.” When asked why, she doesn’t pause.

“He was always spoken of with a combination of profound respect and reverence,” says D’Angelo, one of four Smith grandchildren who spoke for this story. “Even as a young child, I was made aware of his importance.”

D’Angelo doesn’t have many memories of her grandfather from her childhood in Upper Arlington, Ohio — he died when she was 6 — but the ones she has are vivid. She recalls swinging from a giant elm tree in his backyard and watching Smith solemnly read from a large Bible during family gatherings. Her creative life began on the auditorium stage of Jones Middle School, which her grandfather designed, and in the choir at First Community Church, where he was a towering presence.

“The word ‘patriarch’ was part of my vocabulary at a very young age,” says D’Angelo, an Emmy and Golden Globe nominee and costar of “National Lampoon’s Vacation” and its sequels. “There was a reverence for school, an importance placed on education.”

D’Angelo also sheds light on Smith’s career arc, which saw him pass up the likelihood of big-city fame for a life of service to society and students.

“I remember that my mother [Priscilla Smith D’Angelo] told me that Grandpa always believed every professional owed it to the community to teach,” she says. “She referred to herself as a professor’s daughter with great pride.”

That commitment to education was a Smith family value. Born in Dayton, Ohio, Howard Dwight Smith was the son of Andrew and Nancy Smith. His father, a member of the Dayton school board, believed strongly in God, civic responsibility and education as “the path to citizenship,” says granddaughter Cyndi Starr.

After earning two bachelor’s degrees, Howard Dwight Smith (second from left) studied in Europe in 1911 on a Perkins Traveling Fellowship. His scrapbook identifies his peers as (from left) Antonio DiNardo, Ernest Prestwich and Frank Robinson, who shared the field of architecture. (Photo courtesy of Kathie Roig)

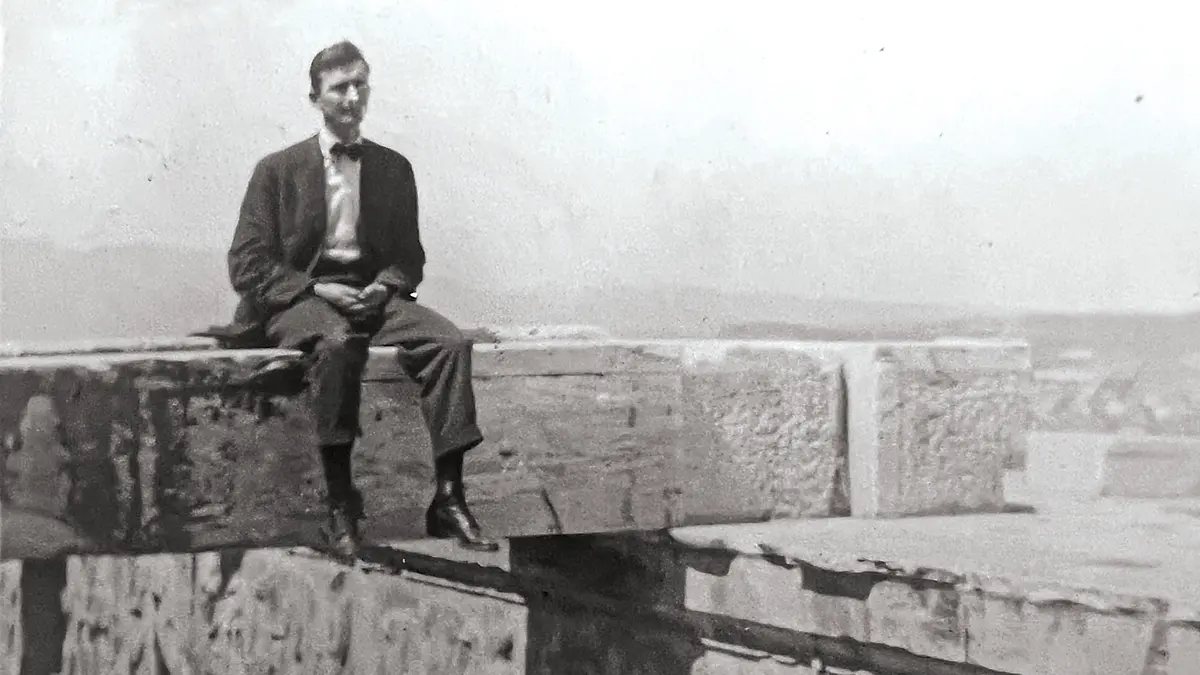

Smith found a prime location for a friend to photograph him when they visited the Parthenon in Athens, Greece. The temple was constructed from 447 to 438 B.C. (Photo courtesy of Kathie Roig)

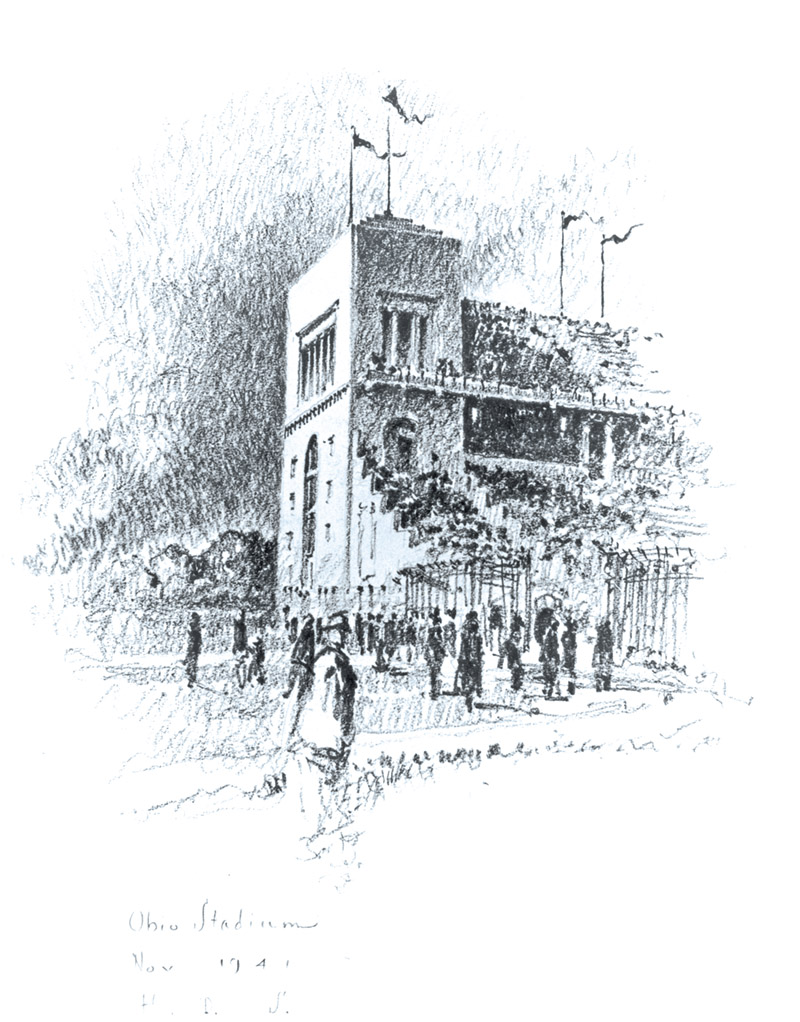

Smith created this sketch of the Pantheon during his fellowship. Built between A.D. 118 and 128, the structure is known for its magnificent rotunda, which Smith later reflected in his design of Ohio Stadium. (Photo courtesy of Kathie Roig)

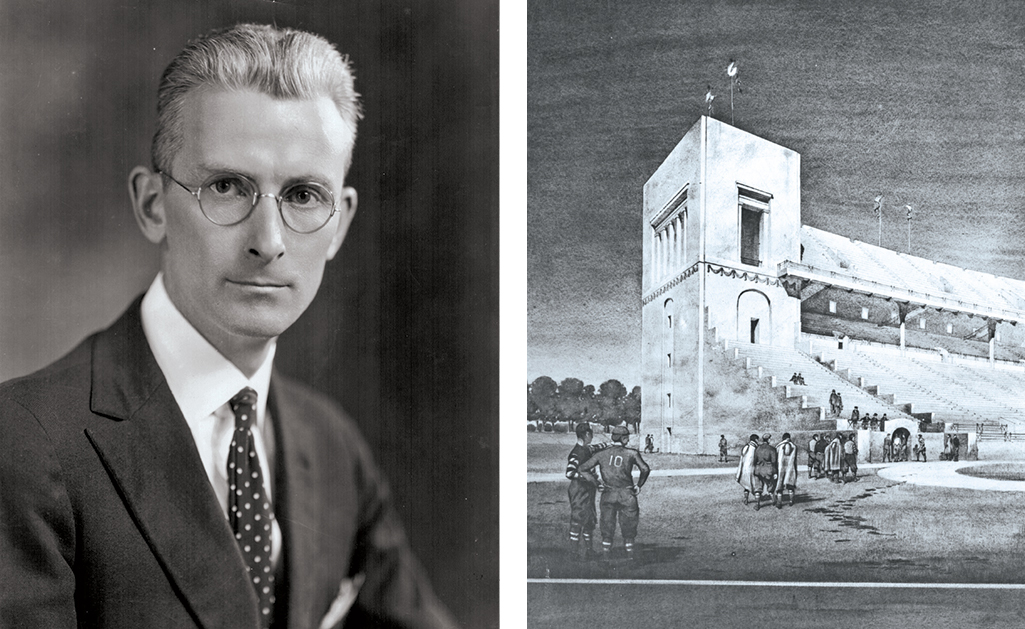

Howard Dwight Smith was an Ohio State scholarship student and worked as an assistant in the Department of Architecture as a senior. He earned his bachelor’s degree in civil engineering in 1907 and a bachelor’s in architecture from Columbia University three years later. In 1911, he was awarded a Perkins Traveling Fellowship that enabled him to spend a year in Europe, where he was captivated by architectural marvels that would inspire his career.

Smith was an artist at heart, and he depicted some of Europe’s seminal landmarks in watercolor paintings and charcoal drawings, granddaughter Kathie Roig says. When it came time to imagine Ohio Stadium, Smith’s fascination with the built wonders of Rome led him to reflect in its design the archways of the Colosseum and the rotunda of the Pantheon.

“Taking his paints out on location or working from sketches later, he painted places that inspired him,” says Roig, who is organizing her grandfather’s work for an Upper Arlington Historical Society exhibit in October.

Smith returned from Europe in 1912 and married Myrna Cott. The couple made their home in New York, where Smith worked for John Russell Pope, an acclaimed architect of the time.

Over a six-year span, Smith was first a draftsman and then a designer of mansions for wealthy industrialists. There’s no telling how much fame and money he could have earned had he remained tethered to Pope, whose firm designed the Jefferson Memorial, the National Archives and Records Administration, and the National Gallery of Art’s West Building.

But Smith, who supported Socialist Party candidates for president, was not driven by income. A biography accompanying his 2009 induction to the Upper Arlington Wall of Honor reads: “He believed that money did not signify a person’s worth and that no one needs more than a certain amount of money to live comfortably.”

An offer to serve his land-grant alma mater as an architect and professor of architecture drew Smith back to Ohio State in 1918. Soon he was tapped to design Ohio Stadium.

“He could have made much more money working in New York City, but he had strong connections to Ohio State,” says Bob Long ’73, a retired civil engineer and Horseshoe historian. “He gave up a pile of money, came back to Columbus and designed a stadium like the one he saw in Rome.”

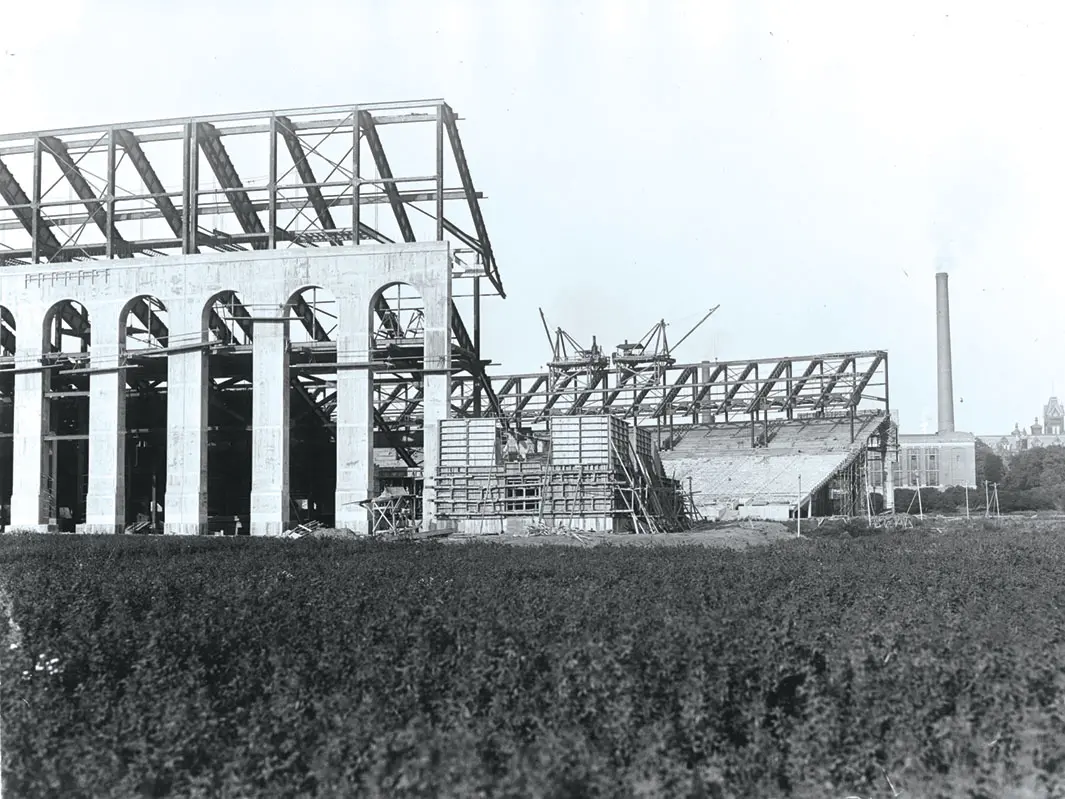

A watershed year in America, 1920 was the first in which more than half of the population was urban. Ohio State enrollment for 1919–20 was listed at 7,817 students, and Long believes university leaders wanted to change the narrative.

“Ohio State had a reputation it wanted to shake,” Long says. “It was known as ‘the college in the cornfield.’”

The Buckeyes had joined the Western Conference, a forerunner to the Big Ten, in 1912. That, along with Harley’s prowess, was raising the profile of Ohio State football. Plus, French was able to facilitate change. An 1895 graduate, he was president of the Athletic Board and an esteemed professor of mechanical engineering.

French knew that Ohio Field, built in 1898 with a seating capacity of about 14,000, could no longer accommodate the huge crowds coming to see Harley and his teammates. As early as 1915, he told the Columbus Chamber of Commerce he envisioned a new venue that could hold 50,000 fans. French and Thompson believed a new stadium — the likes of which only schools such as Harvard, Yale and Princeton had — could raise the university’s stature.

When the time came to select an architecture team for the ambitious project, the obvious choice was up the road in Cleveland. Osborn Engineering already had designed Detroit’s Tiger Stadium and had started work on the original Yankee Stadium. French opted to keep the job in-house, demonstrating his faith in Smith and civil engineer Clyde T. Morris, an 1898 graduate.

“They wanted to show Ohio State had technical degrees as well as agricultural degrees,” Long says. “The company to hire would have been Osborn, but French felt he already had his dream team.”

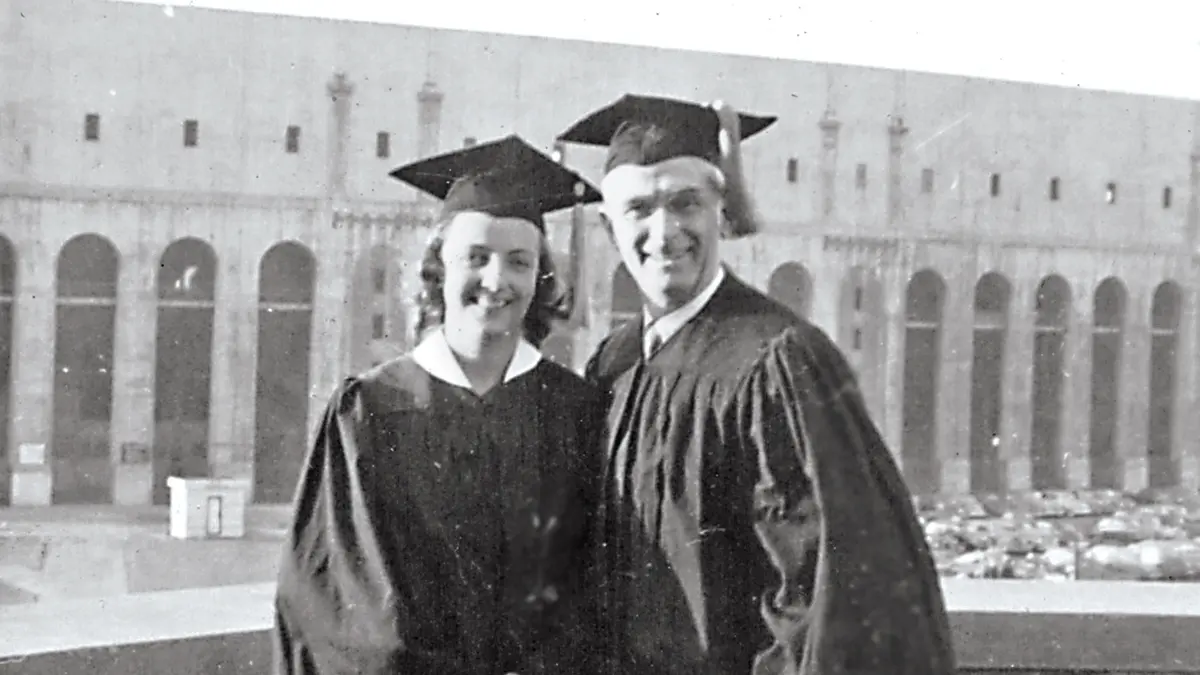

With the ’Shoe as a backdrop, Smith and his daughter Myrna Smith Dupler ’43, ’67, ’74 MA document her graduation day in 1943. Smith had five children with his first wife, Myrna Cott Smith, who died 13 years before this photo was taken. (Photo courtesy of Kathie Roig)

Adopting Thompson’s “think big” mentality, French and St. John prodded Smith to expand his double-deck horseshoe composition until it could hold 63,000 seats. Laid in a line, the wooden bleachers would have stretched 21 miles.

Critics said stadium planners overreached and complained that a 40,000-seat venue would have been sufficient. It wasn’t until after World War II that the Buckeyes regularly sold out, leading some to mock the structure as “Smith’s Folly.” While it took several decades for stadium visionaries to be vindicated, few offered a cross word about the architect’s award-winning design.

“At the time, most stadium projects were done by structural engineers,” says Jack Krebs, Osborn’s director of sports engineering, who worked on the 2019–21 renovation of Ohio Stadium. “Mr. Smith was an architect, and being an architect, he utilized concepts that weren’t really being used at the time in stadium venues.”

In the hands of a lesser architect, all that concrete could have led to an uninspiring design, Greene says, but Smith’s stunning archways and rotunda added artistry. “The Horseshoe remains beloved in large part because of its physical presence,” Greene adds. “This is unique in our culture, which favors new over the enduring.”

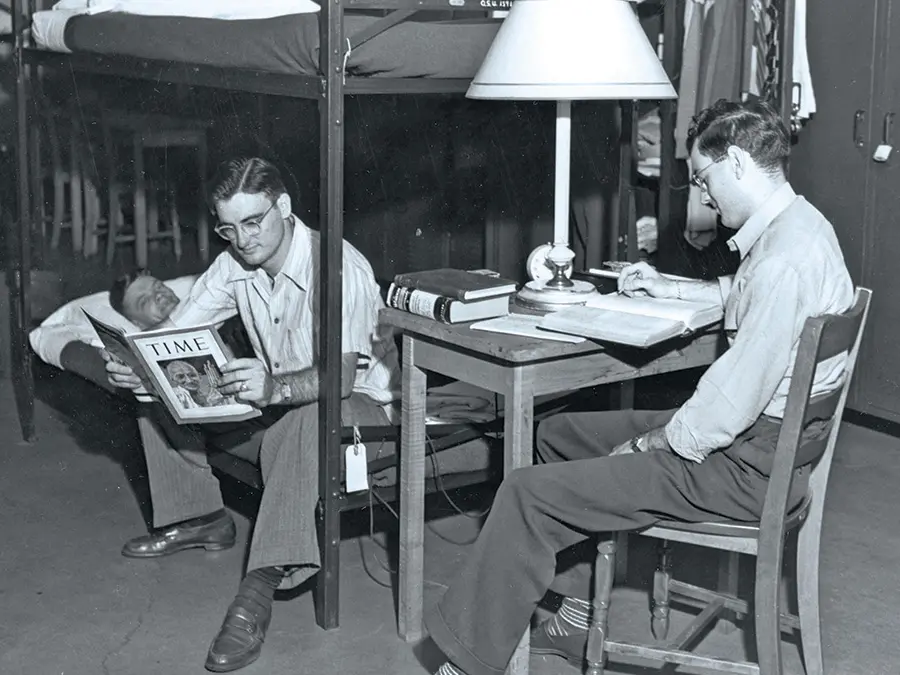

Smith, the man, reflected none of the grandeur evident in his most widely known design. Ever the teacher, he served Ohio State as a professor of architecture during two stretches: from 1918 to 1921 and again from 1929 to 1956, when he was university architect.

Smith immersed students in the work of his office. In a faculty report he wrote in the ’40s, he states: “By placing three qualified students from the Department of Architecture on the drafting room staff in the University Architect’s Office (at regular hourly wages for part-time staff), practical experience is afforded these students during their university course.”

The late Dan Milosevich ’51 was a student of Smith’s, and he recalled his professor as a taskmaster, albeit a generous and humble one.

“He did have very high expectations of his students, but there’s no doubt we all learned a lot because of it,” said Milosevich, who passed away in late August at age 99. “He assigned quite a bit of homework. In fact, I remember one classmate complaining about that to Professor Smith and his reply was, ‘There are 24 hours in a day and how you choose to use them is entirely up to you.’

“One thing I really appreciated was the in-depth feedback he gave his students. It was obvious he spent a lot of time grading our work,” Milosevich added. “Although he was renowned, he did not have an ego and seemed to genuinely enjoy helping us prepare for our own careers.”

Smith maintained his duties as a professor and architect even in the face of family tragedy. In 1930, his wife died unexpectedly at age 44.

“The death of Myrna Cott was a very instrumental moment in his life,” Beverly D’Angelo says. “Think about that for a moment. He’s suddenly a widower with five kids to raise.”

Smith arranged for his sister, Minnie, to come from Dayton to help with the children. In 1936, he married Mary Edith Gramlich, a widow with two daughters.

Family members describe Smith as stern but attentive. Jeff D’Angelo recalls his grandfather taking him to campus in the 1950s to watch the construction of French Field House.

The humility that was so important to him manifested in many ways, including in his practice of never taking more than four tickets for a football game in the stadium he designed, according to a Columbus Dispatch report. His idea of celebrity was sitting near his old family friend from Dayton, Orville Wright.

“I don’t think a lot of people recognize Smith’s [altruism],” says historian Doreen Uhas Sauer, co-author of Forgotten Landmarks of Columbus. “He’s not shouting his name from the rooftops.”

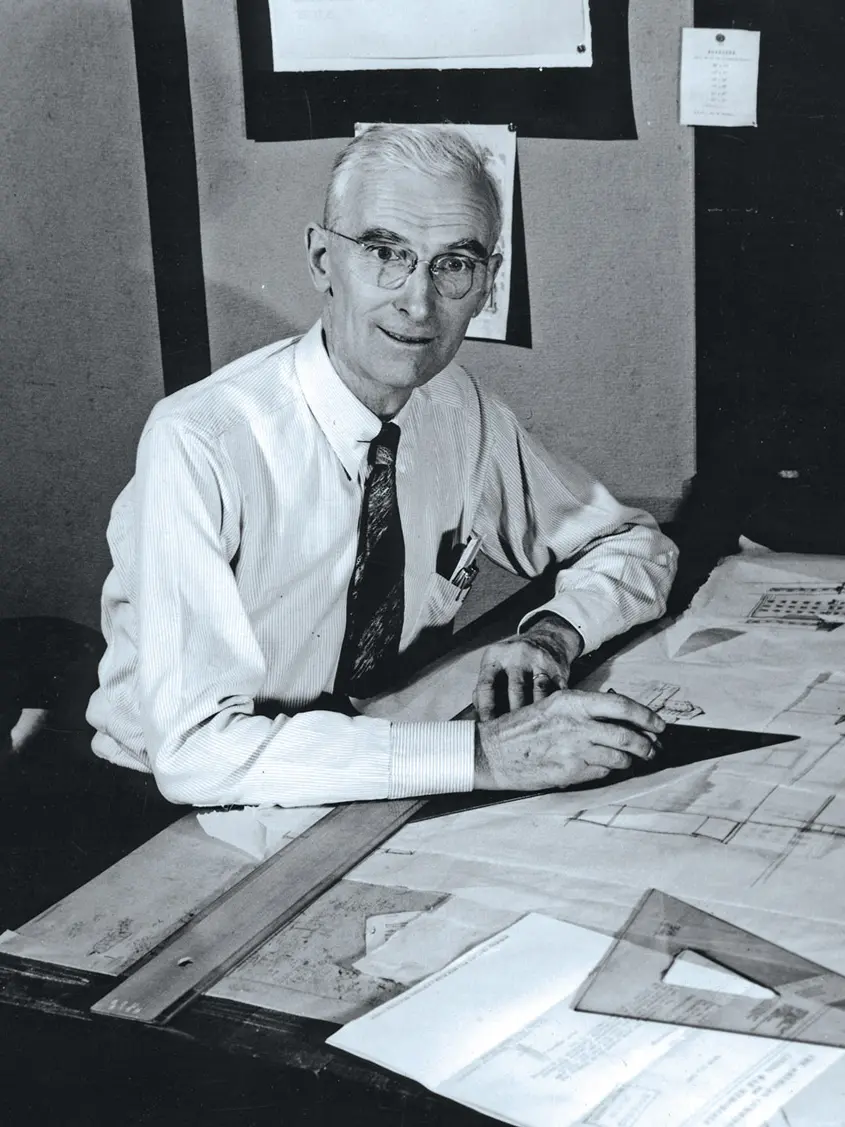

Smith is 72 in this photo, taken shortly before his death in 1958. Besides Ohio Stadium, he designed more than 100 structures during his career, including Poindexter Village and schools throughout Columbus. (Photo from University Archives)

Sauer cites Smith as a key figure in the building boom that transformed Columbus in the 1920s, when he served as architect for Columbus City Schools. Armed with a $10 million budget for an eight-year building project, Smith conceived schools and learning centers throughout the city. He designed an open-air school with heated floors to help combat tuberculosis outbreaks. Indianola Junior High School, another Smith project, became one of the first schools of its kind in America, offering a bridge between elementary and high schools.

He was especially pleased to be associated with Poindexter Village, for which he served as consulting architect. Named for the Rev. James Poindexter, a 19th century abolitionist and Columbus leader, the Near East Side neighborhood was one of the nation’s first public housing developments.

“I’m super proud of Poindexter Village,” granddaughter Roig says. “In a way, that says so much more about him than a lot of things. You know how they say ‘the dignity of work’? His motto was ‘the dignity of where you live and your surroundings.’ Service to others was an important part of his being.”

On Ohio State’s Columbus campus, dozens of building projects owe their success to Smith. He designed Pomerene Hall, the Faculty Club, Baker Hall, Smith Laboratory, Hughes Hall and on and on. Three of his buildings were named for the influential men who risked their reputations to back him as architect on the stadium project: William Oxley Thompson Memorial Library’s 11-story tower and two of his last projects, French Field House and St. John Arena.

In September 1958, shortly after Smith’s death following a stroke, the Board of Trustees named a new residence hall for him. In 2013, a renovation project connected Smith Hall and Steeb Hall, named for Smith’s friend and longtime campus administrator Carl Steeb, who was treasurer of the Ohio Stadium Committee.

By the time Smith retired in 1956, Ohio State enrollment had grown to 22,470 and the football program was on its way to becoming the juggernaut it is today. Ohio Stadium’s seating capacity is now listed at 102,780. One hundred years after critics deemed a 63,000-seat venue folly, the work — as Smith might say — speaks for itself.

“His structures are a reflection of his value system,” Beverly D’Angelo says. “His structures have historical references; they have a reverence for the past. They have a solidity and aspirations within them. They have a perspective that isn’t temporary, which speaks to who he was as a person. Things that you do and things that you leave behind are of value simply because that’s what one should do.”

Leaders who made it happen

William Oxley Thompson

Ohio State’s fifth president believed athletics could raise an institution’s reputation, leading to his firm support for sports teams and facilities, including Ohio Stadium. He encouraged faculty to guide teams along ethical principles. During his 26-year presidency, enrollment grew more than ninefold, an increase attributed in part to Ohio State’s growing prowess in athletics.

Thomas French

The first to envision Ohio Stadium, French served on the Athletic Board from 1912 until his death in 1944. He had earned a mechanical engineering degree from Ohio State in 1895 and joined the faculty three years later, rising to full professor and chair of engineering drawing. French Field House, one of the last buildings Howard Dwight Smith designed, is named for him.

Lynn St. John

St. John joined Ohio State in 1912 as manager of athletics, head basketball and baseball coach, and football line coach. He became director of athletics and head football coach the next year. His football teams won Western Conference championships in 1916, 1917 and 1920, fueling enthusiasm for Ohio Stadium. St. John Arena is named in his honor.

Clyde T. Morris

Having earned his Ohio State degree in civil engineering in 1898, Morris joined the faculty in 1906. He rose to full professor and chair of civil engineering in 41 years with the university, which later awarded him an honorary doctorate of science. Morris served as the stadium project’s structural engineer and also was a member of the Athletic Board.

Let’s all celebrate

The university will mark Ohio Stadium’s 100 years at homecoming October 1. The football game kicks off at 3:30 p.m.

To two-time graduate Sam Rosenthal, CEO of architecture firm Schooley Caldwell, designing spaces is creating great experiences for people.

Nurse Esther Flores ’01 gave up her day job to provide victims of human trafficking with safe spaces and food for mind, body and spirit.

The Thompsons have braved a fraught path to delve into Earth’s climate history and prepare future scientists.