This expert built a mini ’Shoe in his basement

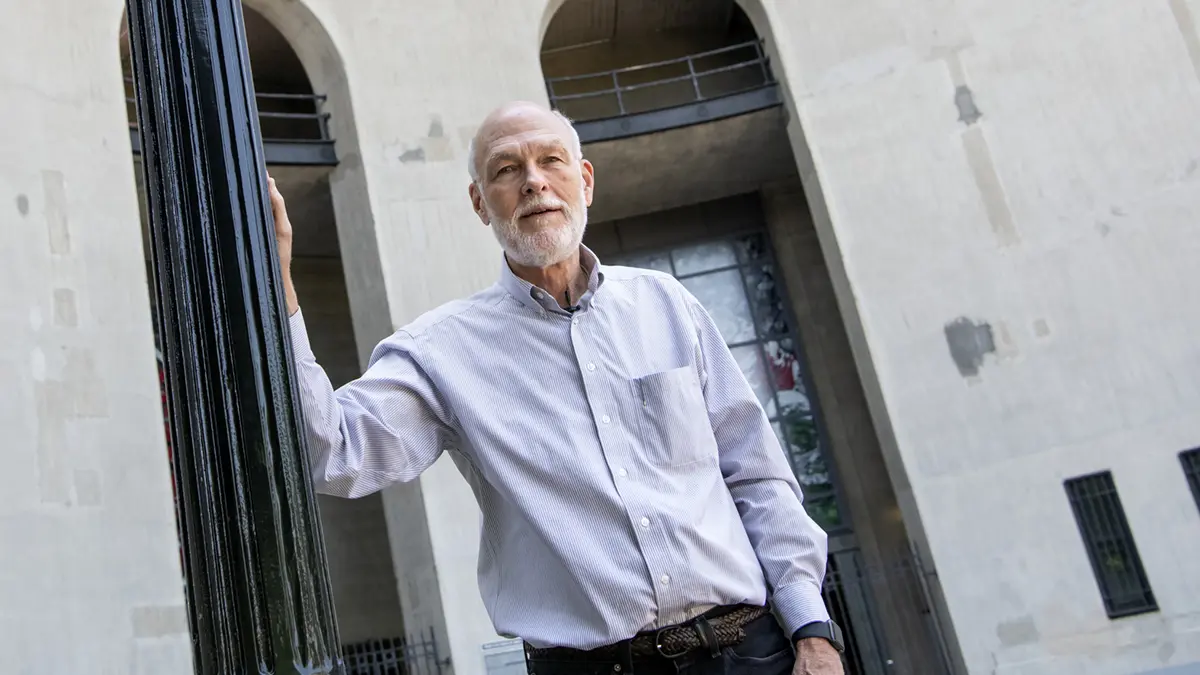

Civil Engineer Bob Long ’73, who worked on the 1999–2001 renovation of Ohio Stadium, has spent a lifetime being awed by “the cathedral of football” and more than 1,000 hours re-creating it.

As a civil engineer and super fan, Bob Long has an appreciation for Ohio Stadium that runs deep. (Photo by Logan Wallace)

Video: ‘The cathedral of football’

In this video, Bob Long shares the origin story of Ohio Stadium, including the bold decision to build a 66,000-seat structure at a time when football game attendance was at 10,000. Run time is 2 minutes 46 seconds. (Video by Daniel Combs and Matt Stoessner)

A devoted fan of Buckeye football, Long had season tickets for more than 20 years, and at games he’d always notice and ponder stadium details — especially in the rotunda, his favorite part. Eighty-five feet high and 70 feet in diameter, the rotunda was so complex in design that it and the two adjoining north towers were still under construction for the first game, a 5-0 victory over Ohio Wesleyan, on October 7, 1922.

The details, history and grandeur of the stadium make it more than just a sporting venue to Long. “It’s the cathedral of football,” he says. “I think it’s the most important structure in the state of Ohio.”

Today, the ’Shoe is in the basement of his Canton, Ohio, home.

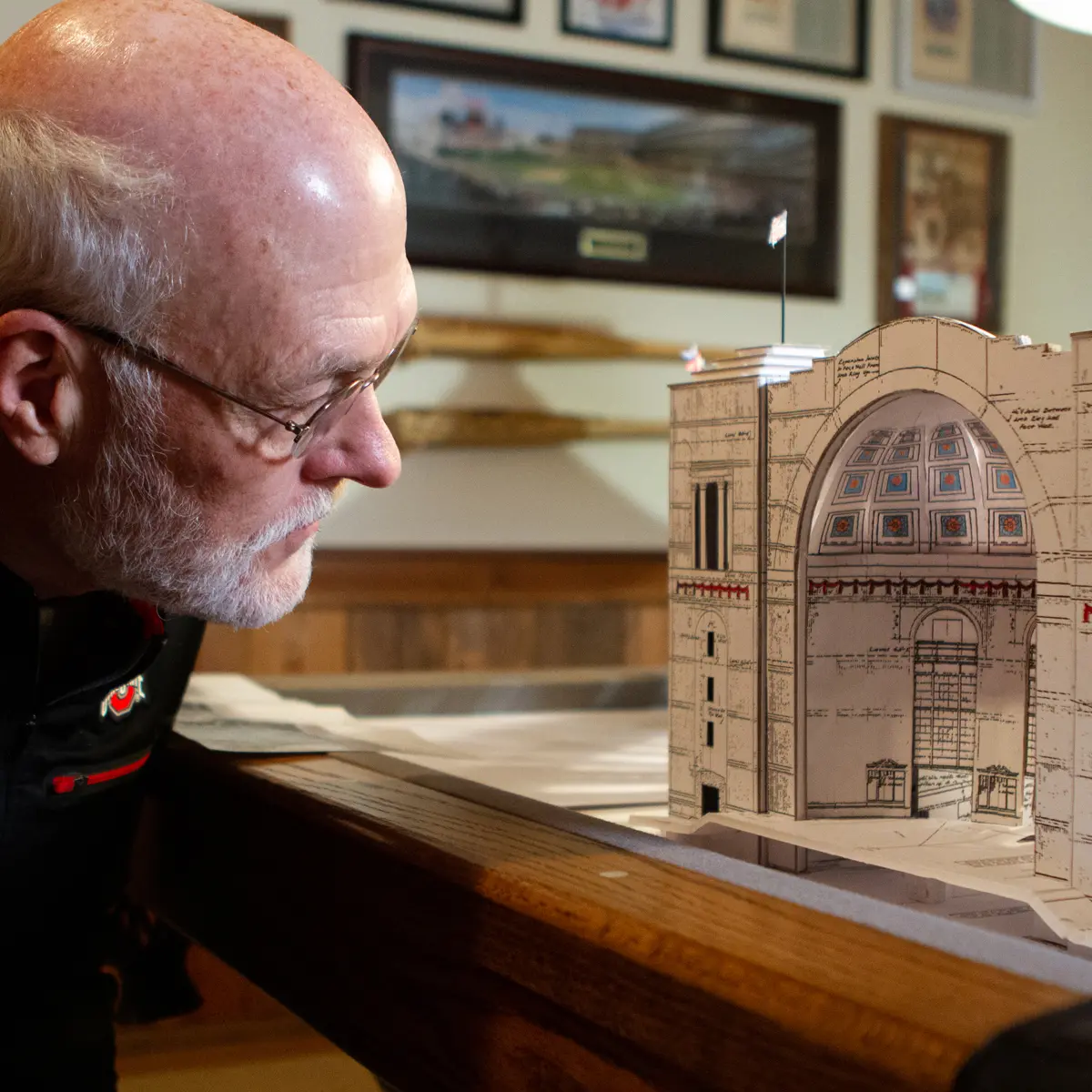

Now retired, Long has constructed a model of Ohio Stadium — 6 feet wide, 7 feet long and 18 inches high — based on copies of the original architectural drawings. One model inch equals 10 feet, 8 inches of the actual stadium.

“I built it because I wanted to know for myself how they did it,” Long says, estimating he spent more than 1,000 hours on the project. Using the original plans gave him a keen understanding of the challenges met and conquered by architect Howard Dwight Smith, structural engineer Clyde T. Morris, general contractor E.H. Latham, their colleagues and construction crews.

With strengthened appreciation, Long took his first full tour of the stadium in May. He and tour guide Don Patko ’92, an associate athletic director who has overseen the ’Shoe for 30 years, fascinated companions with details only experts would know.

Long could hardly contain himself. Singling out one of the steel support members, which allowed for the upper deck to be positioned close to the field, he gasped. “Wow! Now there it is — the mother of all girders. All that C Deck load is being transferred into those columns.”

As the tour ended, Long confided the obvious: “It’s impossible for me to come to this place and not get excited.”

Using Howard Dwight Smith’s architectural drawings of the ’Shoe from the 1920s, Long captured every detail of the iconic venue in a 6- by 7-foot replica he spent more than two years building. (Photo by Daniel Combs)

The crucial choices that set Ohio Stadium apart

Thousands of decisions went into the Horseshoe’s design and construction. To understand the most important ones, we consulted Bob Long, a civil engineer with vast experience in stadium projects and past recipient of the College of Engineering’s Distinguished Alumni Award.

The location

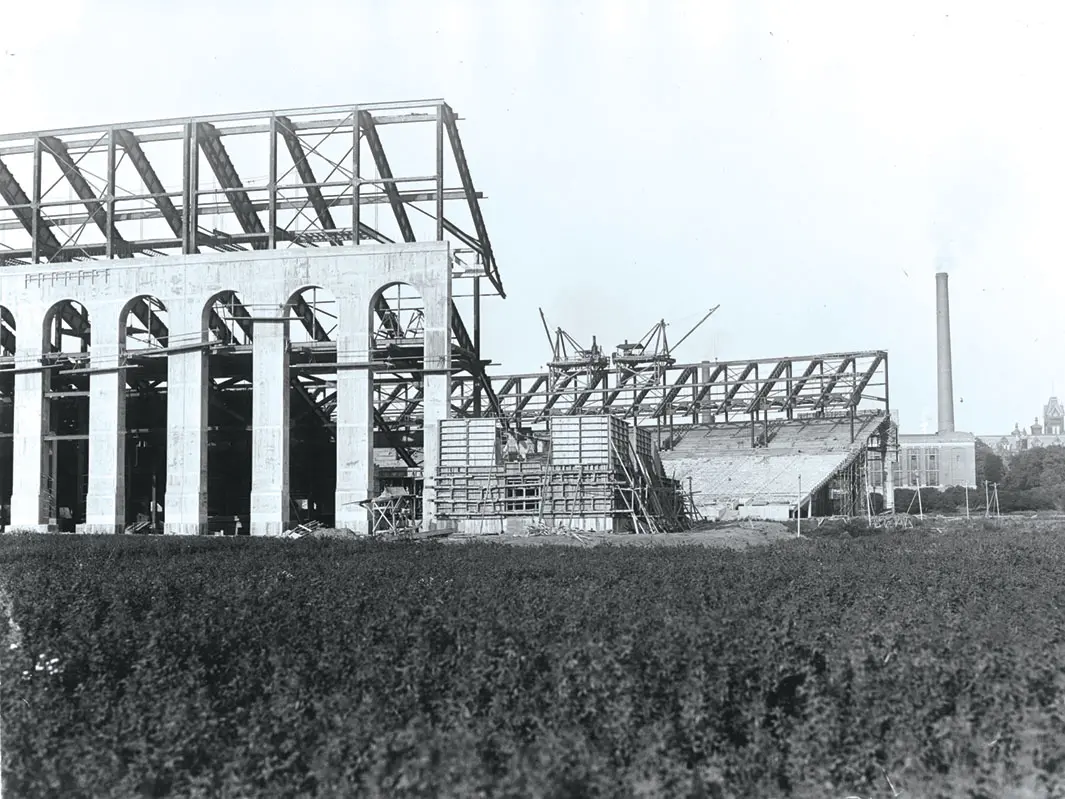

After originally considering a location north of the Oval, the university chose to build Ohio Stadium on 92 acres of cheaper land next to the Olentangy River. However, that marshy floodplain of cornfields meant the stadium needed to be elevated because they couldn’t dig into the ground for a bowl shape. That posed structural challenges. “When you put things in the air, it’s a different story,” Long says. Building above ground required 42,000 cubic yards of poured concrete (weighing 85,000 tons), 4,500 tons of structural steel and 1,300 tons of reinforcing steel.

The shape

This design was chosen to give fans good sightlines and close proximity to the field, improvements over the U-shaped Harvard Stadium that opened in 1903 and the circular Yale Bowl that came along in 1914. Says Long: “What did Ohio State do? They said, what’s kind of like a circle and kind of like a U? A horseshoe — a curved U.”

The materials

Ohio Stadium’s four towers, rotunda and exterior perimeter wall consist of reinforced concrete, while the frame was constructed with structural steel. “That’s the skeleton,” Long says, and those steel girders then were encased in concrete. Many wooden stadiums of the era burned. Ohio Stadium’s steel frame was protected by concrete to negate the risk of structural damage should there be a fire. However, using concrete to encase steel and rebar was rare at the time, drawing cynicism that threatened to derail the approach.

The second deck

Designers realized that one deck to meet the desired seating capacity of 63,000 would leave fans in the top rows too far from the field. The solution: Add a second deck of bleachers. At that time, professional baseball’s Polo Grounds, which opened in New York City in 1911, was the nation’s only double-deck stadium. The upper deck of Ohio Stadium was built with an innovative use of beams, girders and double columns, which allowed more open sightlines for fans sitting below the top deck. “They didn’t have computers; everything was done on a slide rule,” Long says. “It’s kind of mind-boggling.”

The segments

Besides the rotunda and four towers, the stadium is made up of 26 individual sections laid side by side. Those puzzle-piece segments are uniform in nature (except for the greater curvature of those at the closed end) and are slightly separated by expansion joints. The similarity allowed for repetition in construction, speeding up the work pace.