Journey with courageous climate scientists

Lonnie Thompson and Ellen Mosley-Thompson are among the most revered paleoclimatologists on Earth, and their careers at Ohio State have grown in tandem with humans’ understanding of climate change. Paramount for them now is ensuring future scientists are prepared for this vital work.

It was July 2019, and Lonnie Thompson, then 71, was leading a research team that drilled ice cores from the highest peak in the tropics and hauled down 471 meters of glacier ice. The team had spent nearly a month at more than 20,000 feet above sea level on the mountain Huascarán in Peru, where scant oxygen makes breathing difficult, where winds whip at high speeds, where snow falls year-round.

Thompson ’73 MS, ’76 PhD, a distinguished professor of earth sciences at Ohio State and senior research scientist at the university’s Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center, had been leading expeditions to recover ice from the world’s tropical glaciers for the past four decades in order to understand how the world’s climate has changed over thousands of years. He understood the conditions, and he knew how to help his team manage them. They had traversed crevasses, skirted an avalanche and brought the ice to a refugio operated by priests partway up the mountain. They needed to get the ice the rest of the way down the mountain, then to Lima, where it would be placed in freezers aboard a cargo plane and flown to the United States.

But there was one more hurdle: The people who lived nearby were gathering. They were angry. Thompson and his crew did not fully understand their reasons, but one thing was clear: The crowd wanted Thompson and his team gone, and they wanted them gone now.

Lonnie Thompson leads his research team up Peru’s Huascarán, the highest peak in the tropics.

Video: Ice Sages

In this video, the Thompsons and colleagues share the impact of their work, both now and for future generations.

The next couple of years were a blur: Mosley-Thompson earned her master’s. Both finished PhDs. Their daughter was born — they named her Regina, for Lonnie’s sister.

Then, Thompson got another chance at Quelccaya, this time with funding to drill. He assembled a team, packed equipment typically used in Antarctica and headed to Peru. But the team quickly realized conditions were vastly different from those on the world’s southernmost continent. Helicopters couldn’t fly to the mountaintops to drop off their drill and generator. The equipment was too heavy for porters or horses. The trip was, by almost every measure, a failure.

“I could either give up and do what everybody was telling me to do, which was go back to the polar regions, or I could find another way,” Thompson says.

The team had an engineer, Bruce Koci, who designed a lightweight, solar-powered drill that could be carried up a mountain. They built it, then brought in big blocks of ice and piled them high next to a parking garage on West Campus. Carefully, they lowered the drill to the column of ice. It worked flawlessly.

Thompson returned to Quelccaya with the drill, worrying about his professional future. “I figured if I failed twice, my science career was probably over,” he says.

But the trip was a wild success: The team drilled the first cores ever collected from a tropical glacier. They sent samples to the scientist who had declared it impossible to drill on high-elevation glaciers. He later wrote that the isotope records — indicators of the climate present when ice forms — were among the best he’d ever seen.

Mosley-Thompson was building her own career. She drilled her first ice cores in Antarctica, at South Pole Station, in 1982, then returned in 1985. Each time, she was one of few women at the research stations. The men treated her respectfully, she says, but there was a clear divide: The buildings had no facilities for women, because women had rarely been permitted to work in Antarctica. At South Pole Station, while the other scientists shared sleeping quarters, bonding over their adventures and work, Mosley-Thompson was relegated to a separate area.

At the time, the agencies that funded ice core research only supported work near established bases on Antarctica. Mosley-Thompson knew focusing on the same places would only yield the same results. She wanted to go farther into Antarctica to see what the ice there held.

In 1986, she got her shot. Mosley-Thompson chose a site in East Antarctica, near the Pole of Inaccessibility. She named the camp Plateau Remote, after Plateau Station, a tiny American research station that had existed nearby in the 1960s. She was the first woman to lead a remote Antarctic expedition. The other team members were men.

All of Antarctica is cold; Plateau Remote is exceptionally so. Scientists at Plateau Station logged what had been the world’s coldest recorded temperature at the time: -99.8 degrees Fahrenheit.

“It was a surreal place,” Mosley-Thompson says. “The sky is very blue, and the ice and snow are very white, and the sun doesn’t really set, but just circles around 24 hours a day.”

The plane that dropped her and her team off was supposed to return in two weeks with more food and to start taking ice cores back to the South Pole. But when the appointed time arrived, the pilots radioed Mosley-Thompson to say they couldn’t find her camp.

“We could see them circling in the distance,” she says, “but we had no way to direct them to us. Eventually, they left. And that’s how I got ‘lost’ in Antarctica.”

The team was in the middle of one of the coldest and most isolated places on the planet, with nothing but ice and snow for hundreds of miles. Mosley-Thompson knew the South Pole station managers wouldn’t leave her team there, and she had prepared by packing extra food and fuel. So, while waiting for the plane’s return, the team kept drilling.

They collected two 200-meter ice cores that provided a 4,000-year record. Once analyzed, they would show the first evidence of a volcanic eruption that spurred a cold period in the 1800s. The discovery solved a climatology mystery and cemented Mosley-Thompson’s place in the annals of ice core science. She would go on to lead another 13 expeditions throughout Greenland and Antarctica and serve on and lead NSF groups overseeing Antarctic research. Her scientific contributions were so important that a valley in Antarctica is named for her.

On Huascarán, local police had warned Thompson that if he chose to talk with the community, they could not protect him. But Thompson felt he had to meet with the villagers. So, while Mosley-Thompson called in favors across Peru and negotiated with the Peruvian government, Thompson headed down to face the crowd.

In video from that day, villagers stand with crossed arms; some speak in raised voices. One waves a dead fish, accusing the researchers of poisoning the water. Others insist the team was mining for gold.

“If you’re working in a remote area, and an area where indigenous people have lived for thousands of years, you are the outsider,” Thompson says. “And you don’t judge what they believe. Your job is to try the best you can to get them to understand what you’re doing and why you’re doing it.”

Thompson and his team stood before the crowd. He noted the melting glacier, the warming planet, the effect both were having on the community. Then, he listened.

Field seasons in Antarctica occur during the North American winter; those in the tropics are during our summers. For the Thompsons, who were raising a daughter, choosing regions with opposite field seasons made sense.

“I really came to appreciate that as I got older, when I was trying to balance my life and my career, that the decisions they made were deliberate, to try to have the family life balance with the science,” says their daughter, Regina Thompson. “And I didn’t really understand what they did until I was older. I just thought my dad was like Indiana Jones.”

Support this critical work

Ensuring future scientists are prepared to carry on work the Thompsons have dedicated their lives to is a priority for Byrd Climate and Polar Research Center. You can support high school, undergraduate and graduate students who aspire to help the world understand and adapt to climate change.

By the time Mosley-Thompson got “lost” in Antarctica, Regina was 10 years old. Her dad was home with her. There were no cellphones, GPS or satellite phones. At that time, too, the scientific community was sounding the alarm on climate change. But in the mid-1980s, much of the general public did not accept that humans were responsible.

As they traveled through the world chasing ice, the Thompsons became more alarmed. The ice was melting; the glaciers were shrinking. Sea levels were rising, storms becoming more intense. They knew the world was on a dangerous path.

By 1992, they had seen enough. That February, Thompson testified before a U.S. Senate committee about the changing climate and melting glaciers. It was the first time he spoke publicly about climate change. It would be far from the last.

“After that hearing, I got hate mail from people who didn’t believe that climate change was happening or didn’t believe that we humans were the cause of it,” he says. “And the thing I thought then is the same thing I think now: The climate doesn’t care if you believe it is warming or not. It’s happening.”

Over the next decades, as the couple traversed the globe gathering ice, the planet’s atmosphere warmed more rapidly. Deep ice cores from Antarctica confirmed the increasing levels of carbon dioxide after the start of the Industrial Revolution, and it was already well-known that carbon dioxide warms the atmosphere. So, the Antarctic ice showed without a doubt that human activity was to blame.

“It began to feel like we were racing against time, both because the glaciers were clearly melting — and so we had to get to that ice before it was gone — and because we were getting older,” Thompson says

Aging is a great equalizer: If we are lucky, it happens to us all — even Indiana Jones. Thompson was 61 years old in 2009, leading another trip to Peru, when his leg swelled so badly he could barely walk. A doctor there diagnosed him with congestive heart failure

Back at the Ross Heart Hospital at Ohio State, his cardiologist had more bad news: Thompson needed a heart transplant. “I told him, ‘You’ve got to be kidding. This heart has taken me to the top of some of the highest mountains in the world, and you want me to give it up?’

The next year, still fighting the idea of a transplant, Thompson led an expedition to a glacier in New Guinea — ice that was melting rapidly — and encountered four tribes of indigenous people whose religion positioned the mountain as their god, and who thought he was drilling into that god’s skull to steal its memories.

“They were right,” he says. “I was taking the memories — the history — that the ice held. And I told them that the ice was disappearing, that there was no way to prevent that from happening, but that I could save these small parts of the ice in our freezers. I knew that one day soon, the only ice from this glacier that would remain on the planet would be here at Ohio State.”

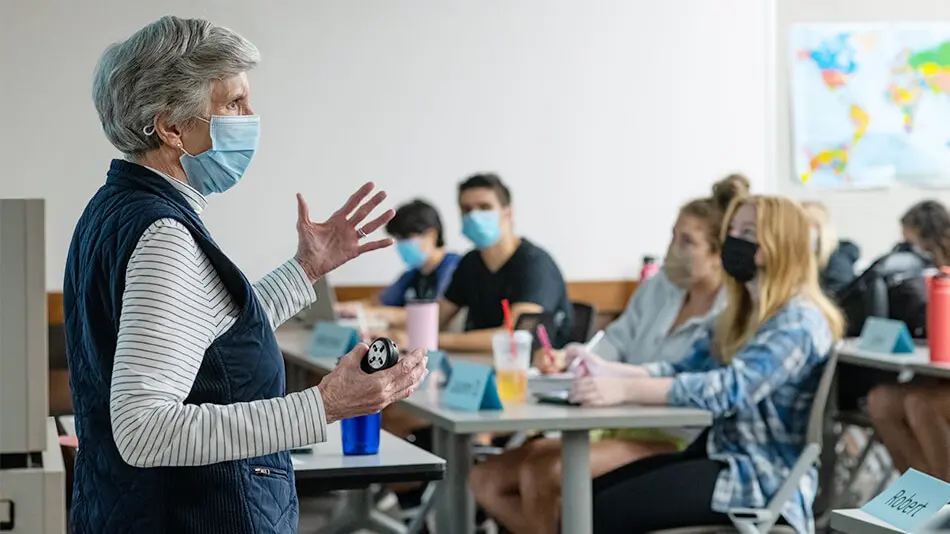

Mosley-Thompson teaches Global Climate and Environmental Change, an undergraduate honors class in the Department of Geography. (Jo McCulty)

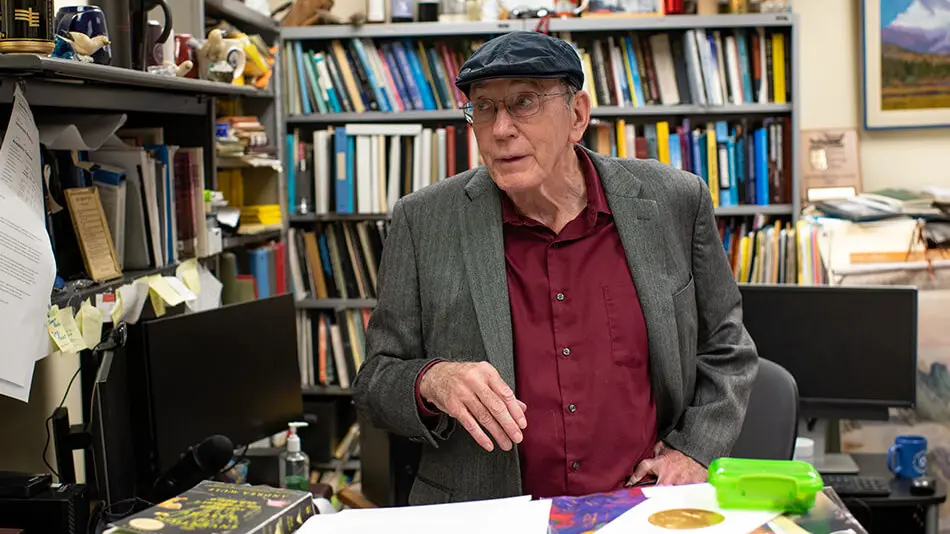

Thompson talks with a colleague in his Byrd Center office, surrounded by mementos from his 48-year career at Ohio State. (Jo McCulty)

For Thompson, the experience crystallized the importance of working with indigenous people near the glaciers. “They have done nothing to induce climate change, and yet they are suffering the worst effects of it.”

Thompson came home resolving to tell the stories of those most affected by climate change and to collect as much ice as he could before it disappeared. But then, while working in the Italian Alps, his heart all but gave out.

He had faced bandits on horseback in the Andes, lived for months at a time at the highest elevations in temperatures well below freezing, negotiated with the Chinese government and tribes in New Guinea. But his heart was out of time.

“He was dying,” Mosley-Thompson says. “His heart was just failing.”

Doctors at the Ross implanted devices to keep his heart working. They added him to the heart transplant registry. But he developed an infection, and the doctors told Mosley-Thompson it was unlikely he would survive.

But survive he did. It felt like a miracle. Yet it would be months before he could walk normally or return home.

Then, on May 1, 2012, while working in his office at the Byrd Center, his phone rang. A matching heart was available. The donor, a 22-year-old man from Coshocton, Ohio, had been an adventurer, too. Thompson underwent the heart transplant that would save his life.

The very next year, he led an expedition to Tibet. Then he went back to New Guinea, where the ice was

all but gone. He traveled to Peru four times. He drilled ice cores in China that have shown some of the most important discoveries of his career, including the fact that microbes and viruses can persist in ice for tens of thousands of years.

“Their work, in a word, has been transformational: The perfect tag team scientist couple, with Lonnie working the tropics and Ellen working the poles,” says Michael Mann, a renowned climate scientist and distinguished professor at Penn State. “And somehow, they still had time to teach, advise graduate students, testify to Congress and write groundbreaking paper after groundbreaking paper.”

In the Musho town square, facing angry and concerned villagers, Thompson continued to listen. One scientist on his team, Roxana Sierra-Hernandez ’05 MS, ’10 PhD, who is fluent in Spanish, translated and negotiated. After several hours, the community agreed to give the team five days to leave — with the ice. Thompson breathed a sigh of relief.

Those cores, he says now, are some of the best records of climate change he’s drilled to date. Both Thompson and Mosley-Thompson believe that in 10 years, the ice atop Huascarán likely will be melting. And while they and other researchers are now analyzing the ice Thompson’s team collected, parts of those cores will remain preserved in the Byrd Center freezers for future generations.

Both are 73 now, and while their work is far from over, they also know that future scientists will find things in the ice that they haven’t yet considered. And they continue to speak out, despite the anger climate researchers often face.

“I have watched their careers evolve, and I see the change that they’re making right now to make themselves more available to media and to interviews,” Regina Thompson says. “They believe it is important to tell the story of climate change.

“They have so much to offer in the way of inspiration: My mom, a successful scientist, had a child and all the things that come with that; she’s nuclear-powered. And my dad’s superpower is that he is so creative, and his power of positivity is unlike almost anything I have ever seen. He is always convinced that it’s going to get better, and he’s convinced that it’s just around the corner. And today could be the day.”

Help preserve discovery

The Byrd Center freezer for ice cores has exhausted its capacity. You can help with the purchase of new freezer equipment to store ice cores gathered on future expeditions.