Inside the world of a servant on the streets

Nurse Esther Flores ’01 gave up her day job to care for victims of human trafficking. Now she helps them meet basic needs by providing safe spaces and food for mind, body and spirit.

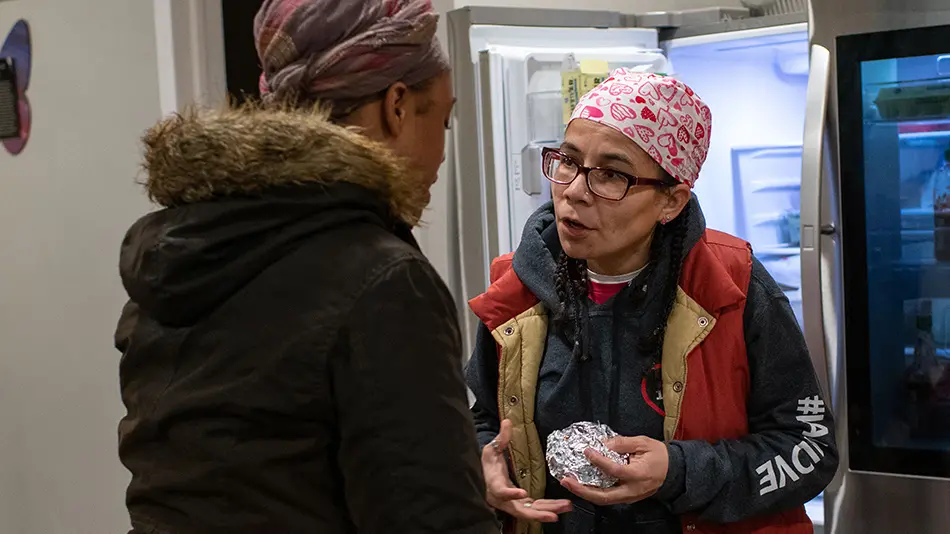

Flores, shown listening to a woman at her charity’s Love Drop-In Center, always wears bandannas so people on the street who might not know her name can recognize her.

Challenging the norm

Flores, who has an MBA in health care administration from the University of Phoenix and two undergraduate degrees, walked away from a day job in nursing to focus on her charity.

That courage to change course grew from a familiarity — a comfort level even — with hardship.

A native of the Bronx, New York, Flores was raised in the projects by a single mother. She grew up watching many of her friends’ lives ruined by drugs and sexual exploitation, and she witnessed the inequities of a health care system that provides the most vulnerable with the least care.

“I grew up in poverty,” Flores says. “I know poverty, what it does to people and how it can drive you to do things you never thought you would, to survive.”

Flores moved to Ohio after completing a bachelor’s degree in physical anthropology and biochemistry at Lehman College, part of the City University of New York system. She eventually enrolled at Ohio State, where she earned a second Bachelor of Science, this one in nursing.

“Ohio State ignited a fire to my critical thinking,” she says. “I’m that person who always asks questions and if I don’t get an answer, I try to find one.”

For years now, Flores has been asking why society demonizes the women it labels prostitutes. Throwing them in jail hasn’t worked, and it’s still not working, she says. “We need to get the word ‘prostitute’ out of our vocabulary. I see broken souls that need healing, not incarceration.”

Molly, a peer supporter and survivor of human trafficking, cares for the women alongside Flores.

Her reasoning is grounded in how society defines prostitution and sex trafficking, and what it means to be a victim. In prostitution, a usually desperate woman sells herself; in human trafficking, someone else, such as a boyfriend, pimp or cartel boss, pushes her into it and then profits from it. Ohio law codifies that distinction, but in Flores’ experience, trying to pinpoint the difference feels pointless.

Every single woman she meets through her charity is being trafficked.

“They are being coerced into selling sex and someone else is benefiting from their pain,” Flores says.

Fighting trafficking

Flores sees it all the time: girls or women threatened with harm or manipulated with hollow promises of a safe place to live and money for their kids. Others forced into silence to safeguard their immigration status. Or groomed from a young age by family members to sell sex as a means of income.

Columbus Police Sgt. Fred Brophy ’00, who has worked with Flores since 2018, observed the same thing in his more than 20 years working on the city’s west side. “This is not an issue of free choice,” he says. “These are women who society has forgotten, and what Esther is doing is bringing a layer of humanity to the problem.”

Those Flores serves come from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds; some dropped out of school, others hold college degrees. They range in age from 67 to young teens. Many have aged out of foster care.

What unites these victims is the tremendous burdens they carry: homelessness, addiction, a history of physical and sexual abuse, mental health disorders and overwhelming feelings of isolation and fear — vulnerabilities that traffickers eagerly take advantage of.

“Human trafficking is very real, and it’s impacting every city and county in the state,” says Jennifer Rausch ’99, ’02 JD, legal director of the Human Trafficking Initiative in the office of Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost ’84. In fact, Ohio has ranked among the worst six states in the nation for number of calls to the National Human Trafficking Hotline for five years.

The situation can feel hopeless, but people throughout the state and around the globe are working to raise awareness and help victims restore their lives.

Rausch leads a team whose goals include strengthening state laws used to prosecute traffickers and johns. The team hosts an annual Human Trafficking Summit to educate service providers.

At the Love Drop-In Center, Flores makes sure a woman who came in from the cold gets food to take with her.

Flores works in the trenches, where she tends to the physical, spiritual and emotional wounds borne by women who are trafficked.

Her commitment has inspired support from city officials and private citizens alike. For example, in July 2021, Columbus City Council awarded Flores’ charity a grant of more than $100,000 to increase outreach to victims of trafficking.

A chance meeting inspired Doug Sheffield ’75 JD to help. He sat next to Flores at a seminar for victims of trauma, which he attended as a Court Appointed Special Advocate (CASA) volunteer for abused children.

“Esther had a level of passion for her charity that I wanted to help foster,” he says.

The accountant and financial advisor admired how she navigated the complicated process to secure 501(c)(3) status for 1DL2H. He went on to donate the house that would become the Love Drop-In Center.

There was special meaning behind the gift: Sheffield’s wife, Tracy Williams Sheffield ’77, ’85 MBA, had recently died of acute myeloid leukemia.

“I wanted Tracy’s legacy of love and care to continue,” he says, and in Flores’ work, he found that nurturing spirit thriving.

Supporting 24/7

The Love Drop-In Center serves as a haven for women, their children and transgender individuals trapped in sex trafficking. “I am proud to say that we are the first in Franklin County to open a full-time center for human trafficking victims,” Flores says.

Her charity, which she founded in 2015, also operates two safe houses where survivors of human trafficking, domestic violence and substance abuse can stay overnight, one on the northeast side of Columbus and one in the Hilltop neighborhood on the west side.

After Flores finishes working at those locations, she goes out on the streets in one of the organization’s two Love Bugs, vans stuffed with food, clothing, first-aid supplies and Narcan. In the darkness, she scours sidewalks, alleys, abandoned houses and homeless camps, helping 40 to 50 people a night.

“What is unique about us,” Flores says, “is we are trauma responsive with a nursing and a harm-reduction approach, meaning we meet people where they are.”

A registered nurse, Flores treats wounds and other injuries for those who stop in.

The streets are where Flores first came across a homeless woman named Keara, who requested anonymity so she could candidly share her story. Addicted to drugs and selling sex to survive, she had lost custody of her children and had zero expectations for a future off the streets.

“I had never experienced love until I experienced Esther,” Keara says. “She literally chased me down the street in one of her Love Bugs to help me. … She told me she would connect me with services to get me off the street, but I just wasn’t ready.”

Then, one evening after a drug-induced blackout, Keara found her way to the only place open, the Love Drop-In Center. Flores tended to her wounds and gave her food for body and spirit.

That night, Keara found the hope she needed to see a way forward.

“People don’t understand that it’s a split-second decision to get clean, to get off the streets,” she says.

“And if you have no place to go, no one to take you in, you lose.”

Keara’s been clean for two years. She works two jobs, has her children back and plans to pursue a degree in mortuary science.

Believing fiercely

Today, Flores describes herself as “a nurse who carries a nursing bag, taser, pepper spray, brass knuckles and a knife to protect myself and those I care for.” She wouldn’t have it any other way.

Still, she acknowledges that if she gave herself time to stop and think about what she might face every night, she wouldn’t get out of bed.

It can feel like there are never enough resources to mend the bodies and spirits of the girls and women she encounters. And the need for her kind of humanity grows each year as the number of victims of human trafficking and domestic violence increases.

Flores comforts a woman in crisis. Her charity helps women cover basic needs, but it also offers them solace and hope.

In 2021, Flores’ charity served close to 6,000 women, and the problem isn’t going away.

Despite that, Flores doesn’t see giving up, or sleeping in, as a choice. She pushes forward every day because of her faith in God and her belief that love is transformative.

“These women have become my family,” Flores says. “They see me as a mother, a sister, and they trust me. I am honored to serve them.”

She’s not finished growing her charity to make that happen. Flores’ wish list includes starting drop-in centers elsewhere in Columbus, opening a safe house for pregnant trafficking victims where their children also can stay and adding more employees, so no woman who needs help is turned away.

As a trafficking survivor and a Love Drop-In Center staff member who continually sees Flores’ mission in action, Molly believes in the work and the women. A state-certified peer recovery supporter, she is now studying for a degree in addiction and recovery services at Clark State College in Springfield.

“These women are me, and they desperately need our love and compassion,” Molly says. “With each small act of kindness, with each act of love, Esther gives someone hope.

“And maybe one day it’s enough to spark a change.”