Soul mates and science: Here, he found 2 loves

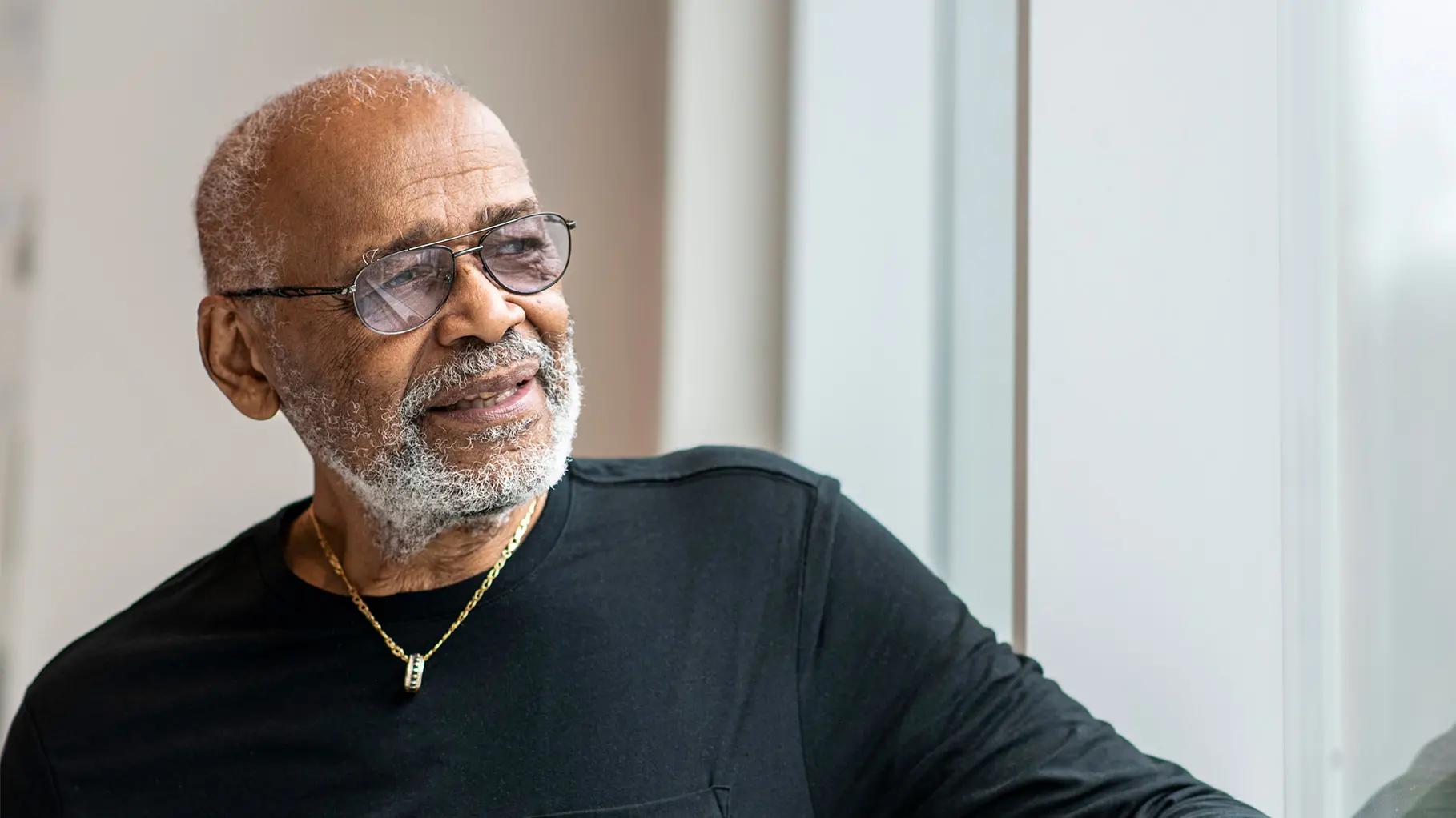

On a campus hundreds of miles from the world he had known, Howard M. Johnson found the path to a bright future. Now, he and his late wife, Nancy Elaine Byrd, are lighting the way for others.

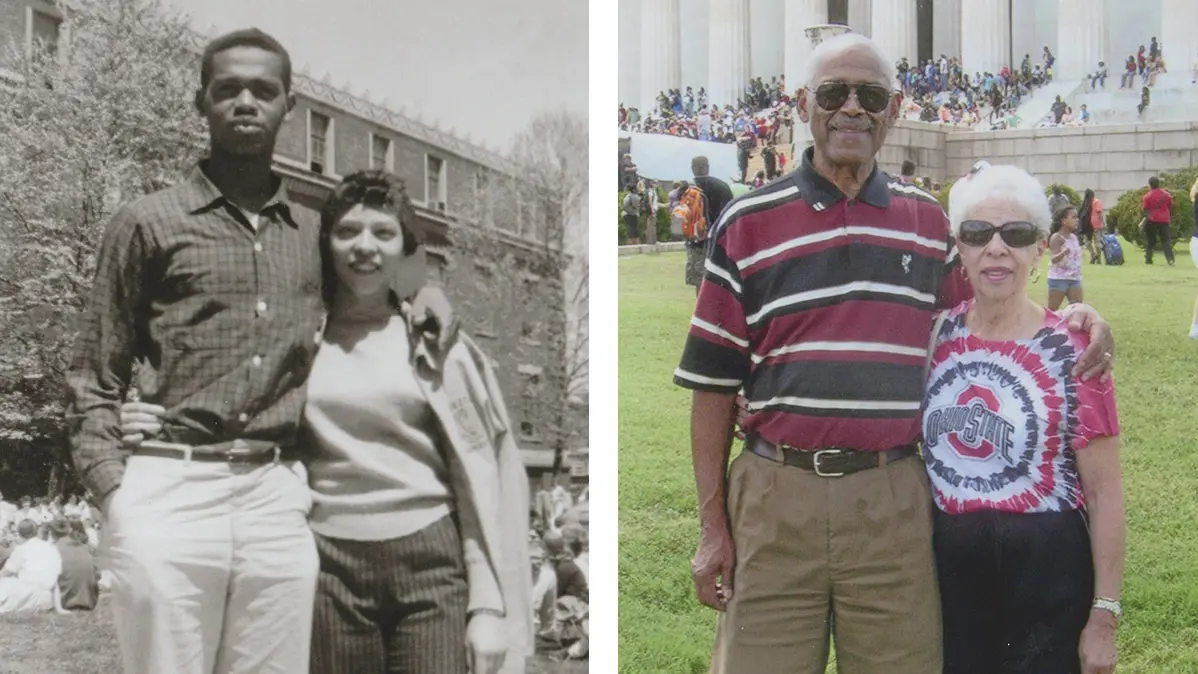

Johnson and Nancy Elaine Byrd met in 1958 — when he was a cash-strapped student and she’d pay for their dinners out — and married soon after. They went everywhere together, including hometown events and scientific conferences around the world. “We were each other’s best friends,” Johnson says. (Photos courtesy of Johnson)

Tears fill his eyes at a mention of his wife’s death from leukemia in June 2019. To honor her, he created the Nancy Byrd Johnson and Howard M. Johnson endowment at Ohio State to support students’ research in fields such as biophysics, molecular genetics and gene activation.

“I hope to spark and support a student who is brimming with curiosity and creativity,” Johnson says. “The main thing is to add a little juice to their creativity and facilitate bringing that out.”

Bold ideas, Johnson attests, aren’t enough. We all need helping partners — in labs and in life.

Friends and colleagues describe Johnson as a fearless, focused and hardworking mentor who cut through the clutter of nonsense, be it bureaucratic morass, extraneous scientific information or worse. His resoluteness, peers say, powered through barriers not faced by white scientists.

“Howard was able to make significant contributions to science in the face of a lot of prejudice,” says friend Bruce Zwilling, an Ohio State professor emeritus of microbiology. “He was able to overcome all of that because he’s very smart and he persevered. His tenacity helped him get funding and also gain recognition for the seminal observations that he made.”

Johnson recalls sometimes feeling angry and bitter about the racism he faced as a professional, but he says he didn’t encounter animosity tied to race as an Ohio State student. Rather, he developed lifelong friends, such as Nancy Bigley, a laboratory partner when both were graduate assistants in the late 1950s.

“Nancy really had an effect on me in terms of her creativity, her animation, her wonder,” he says.

Johnson, in turn, influenced Bigley ’55 MS, ’57 PhD throughout their interconnected careers. She credits him for teaching her to be firm in defending her work — which, remarkably, she is still doing at age 90 as a professor of neuroscience, cell biology and physiology at Wright State University.

“Some of the problems that a Black man has faced in science and education, white women have also faced,” Bigley says. “People don’t take you as seriously. You couldn’t be as good as anybody, you had to be better. Howard was very, very helpful in me developing a spine.”

Ed Blalock is another researcher who benefited in ways beyond science from collaborating with Johnson. They co-authored many seminal research studies at Florida and the University of Texas Medical Branch, and Blalock says their work together also taught him to recognize discrimination and how to respond.

“We couldn’t be from more disparate backgrounds,” says Blalock, an endowed chair in pulmonary disease at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “My family has lived in the same place in north Florida for 200 years, and we were plantation owners, with all the baggage that comes with that. And here’s Howard, great-grandson of a slave. That we became colleagues and such friends has always interested me.

“It became apparent to me that Howard wasn’t accorded certain things [in the scientific community] that would have been accorded to him had he been white. He opened my eyes to that, and he also made it pretty clear to me that I, as a gay man, had to stand up for myself.”

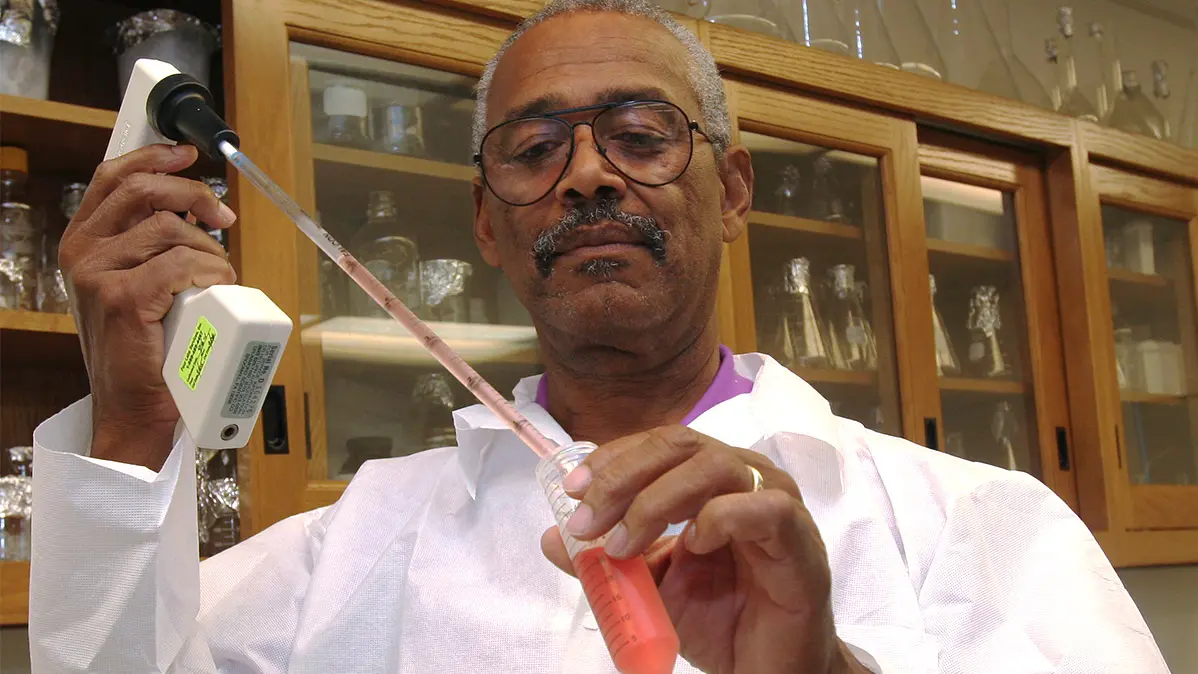

Johnson’s research in microbiology and immunology earned him the respect of peers, including Dr. Anthony Fauci. (Photo courtesy of the University of Florida)

Johnson’s lab work through the years not only inspired his colleagues, but improved treatments for cancer and multiple sclerosis. (Photo courtesy of the University of Florida)

Johnson has constantly stood up for others, helping them see how to do so for themselves. As a professor at Florida, he served on committees for 47 PhD students and eight master’s students, and he trained 14 postdocs. He called his lab “the United Nations.”

“It was the most diverse lab I’ve ever worked in,” says Prem Subramaniam, now an associate research scientist at Columbia University. “We had students from Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan and Lebanon, and someone from India, a couple of African Americans and me, an American from India.

“A lot of that filters from the top down. Dr. Johnson said to the students, ‘OK, you guys are capable, and I don’t care what your background is if you promise me that you’ll do the necessary work.’ He had a way of looking at students that was quite different. He became a father figure to some of us.”

Those Johnson mentored say he empowered them. “He was confident enough in his own ability that he could easily hand off praise to someone else,” says Lindsey Jager, a laboratory manager at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Johnson’s former students say he made certain their names appeared before his own on published research papers whenever their work warranted. He’d share his grant proposals as examples to help them write their own. He demonstrated empathy.

“Dr. Johnson is not very verbal, but he actually shows his kindness by doing things,” says Janet Yamamoto, a professor of immunology in the University of Florida’s College of Veterinary Medicine. “You don’t even realize it until later on. He doesn’t want anybody to face the obstacles he faced, and that’s why he came to the rescue a lot, especially for his students. To me, that kind of mentoring is everlasting.”

The sense of togetherness that existed in Johnson’s laboratory was an extension of his most beloved partnership: his marriage to Nancy. “She was the engine that drove us,” he says.

When they were together, the hard world softened. Possibilities burned bright.

“Nancy was a very warm, open person,” Bigley says. “Howard was always so serious, thinking about what he was doing. They were a great match. They were the love story of the century.”

Nancy Bigley and Johnson reconnect at Wright State University, where she continues to serve as a professor of neuroscience, cell biology and physiology. (Photo by Erin N. Pence)

As her aggressive leukemia progressed in 2019, Nancy made a recurring late-night request as Howard prepared to leave her bedside: “I want Johnny Mathis to put me to sleep.”

Howard would play songs by his wife’s favorite singer in the stillness of the hospital room — and it was 1958 again. Mathis tunes played in Charbert’s Sandwich Shop along High Street during their Sunday dates in that magical year. “I had no money,” Howard says, and so Nancy bought their dinner.

The love that bloomed at Ohio State never faded. Today, he wears her wedding ring on a necklace, and he ponders the disease that took her from him.

Did you fall in love on campus?

Nancy Elaine Byrd said yes to Howard M. Johnson’s marriage proposal alongside Mirror Lake about three months after the Buckeyes found each other, leading to 61 happy years together and two sons. Email AlumniMagazine@osu.edu to tell us your love story.

“We don’t know how the gene mutations involved in my wife’s leukemia were activated,” Johnson says. “The cells of the immune system will kill anything if they recognize it as foreign, but they have trouble recognizing cancer cells as foreign. Cancer cells are very good at disguising themselves as being part of our normal cell makeup.

“In my mind, the future of significant progress in treating cancers is immunotherapeutic. We need creative thinking about how those immune cells deal with mechanisms. It’s like putting together a puzzle.”

Johnson hopes the bold ideas of future problem-solvers can flourish with help from his Ohio State endowment. In February, Kristin Chesnutt, a graduate student in biochemistry, was named the first recipient of the endowment’s scholarship.

“As someone who benefited from the generosity of his time,” Jager says, “it doesn’t surprise me at all that this endowment is something that he and Nancy would want to do. They were always invested in helping others get to where they wanted to go, and in helping people take those first steps.”

Those first steps Johnson took at Ohio State 68 years ago began a journey that amazes his family.

“I go by campus all the time,” says his 95-year-old uncle, Warren Gregory, who lives in Central Ohio, as he did in 1954. “Every time I go by there, I think, How did Howard achieve what he achieved coming from where he came from? It’s mind-boggling.”

Today, Johnson holds fast to another vision, one in which the young scientists who benefit from the endowment make breakthroughs that help generations to come. In that, his own past will serve the future and keep Howard and Nancy present at Ohio State.

“We’ll always be here,” he says.