This Grammy finalist’s job: Teach music, spread joy!

Katie Paulson Silcott ’02, ’10 MA spends every day sharing with her middle school students the power of music to build confidence and unite people.

In this 2 minute video, Katie Silcott explains why music matters for her students — and everyone — as her classes happily practice some songs. (Video by Daniel Combs)

Silcott never wavered from that choice, and her choir teacher at Solon High School, Dave Curtiss ’72, encouraged her to audition at Ohio State. Silcott liked that Columbus was only about two hours from home but worried about the size of the university. “I thought it would be overwhelming. But when I went to tour the School of Music, it felt so much smaller, like a family,” she says.

“It was obvious Silcott relished her education, recalls former Ohio State Professor and Director of Choral Activities Hilary Apfelstadt. A member of the Women’s Glee Club, Ohio State Chorale (formerly Symphonic Choir) and University Chorus, Silcott and friends petitioned Apfelstadt for an independent study to work on building their repertoire and conducting. “They were doing this on top of 18 or 20 credit hours,” Apfelstadt says, “and they weren’t getting a grade.”

After graduating, Silcott took a job expanding the vocal music program at Marysville High School in Central Ohio. Three years into her career, she returned to Ohio State to pursue her master’s degree, also in music education, and attended classes for five summers while working full time. During that period, she transitioned from the high school to the middle school in Marysville.

“I know people say, ‘Middle school? That’s crazy! How do you do that?’ But I just love it,” Silcott says. “I think it’s because that’s when I first discovered choir and how awesome it was.”

Apfelstadt says choosing to teach middle school choir has been a rare act among her former students.

“Especially with those young tenors and basses, their voices are changing. They never really know what’s going to come out,” she says. “They’ve got to have somebody who’s constantly encouraging them. Katie has to find a piece that will not only be interesting for them but will be technically possible for them.”

Apfelstadt visited Silcott and her classes in the spring. “She is in her element,” Apfelstadt says. “Engaging that 12-year-old mind is a challenge, and it takes a teacher with a lot of passion and this relentless sense of enthusiasm.”

As a former student of Silcott’s, Grace Sowers ’12 can attest that Silcott brims with those qualities. She observed it from the instant they met, when she was an incoming freshman at Marysville High School.

“We found out there was a new choir teacher and she wanted to see the new students,” Sowers says. “I vividly remember her coming in. Literally, when she walked through the room it was like sunshine. I thought, ‘I have to be in this choir.’”

While at Ohio State, Silcott says, she looked up to Professors Hilary Apfelstadt, David Frego, James Gallagher and C. Patrick Woliver, and that made returning mid-career to pursue her master’s a natural decision.

It was a fateful meeting for both women, who spent the next several years growing up together in a way, one through adolescence and the other through young adulthood. “She was just able to connect with us. She was very professional, but very relatable,” Sowers says. “She was able to laugh at herself. She made us quirky freshmen comfortable with ourselves.”

Sowers joined Silcott’s show choir, a close-knit traveling performance group, and Silcott joined community theater productions organized by Sowers’ dad, Scott Underwood ’81. Silcott — still Katie Paulson then — played Marian Paroo in “The Music Man” one summer. “This young high school teacher completely wrapped her arms around all Marysville,” Sowers says.

Sowers went to Ohio State to become a special education teacher, worked in Indianapolis for three years, then moved back to Ohio. That’s when she reconnected with Silcott and her husband, Jason Silcott ’05, who were starting to raise their sons, Jack and Charlie, who are now 11 and 9.

Sowers was working at Shanahan Middle School when the choir teacher position opened in 2018. Josh McDaniels, the school principal, recalls: “Grace came to me and said, ‘You think I’m a positive person and I’m energetic? You ought to meet my friend Katie. She is why I am who I am today.’

“Katie is one of the best hires I ever made,” he says. “That’s not an exaggeration.”

The hard stuff

These days, Silcott finds herself telling students: “If we lived through these past couple years, you’re gonna be OK for sure. You can do hard stuff.”

Silcott’s school district, Olentangy Local Schools, closed in March 2020 when COVID-19 was spreading and at its most unknowable. “We felt like we were building the plane while we were flying it, but we were doing it together with a lot of grace and patience,” Silcott says.

She created a plan for remote learning — Musical Monday, Technique Tuesday, Wellness Wednesday, Theory Thursday and musical grab-bag Fri-Yay — that struck a balance between nurturing individual students and preserving the sense of community they’d created in the classroom. But when students started needing something different — especially the eighth graders, whose expectations for end-of-year rituals were fizzling — she evolved her approach.

When classes began the next year, the school had yet another new model: Half of students stayed home while the other half met in person, and then the cohorts rotated. The same teachers taught both groups. Yet some members of the community, angered by the hybrid approach, called for pay cuts.

“I had teachers in tears regularly in my office wondering if they were going to make it through,” McDaniels says. “Our teachers are passionate about what they do. They weren’t willing to say, ‘Do problems 1 through 20 at home.’ They wanted to do something meaningful for the kids.”

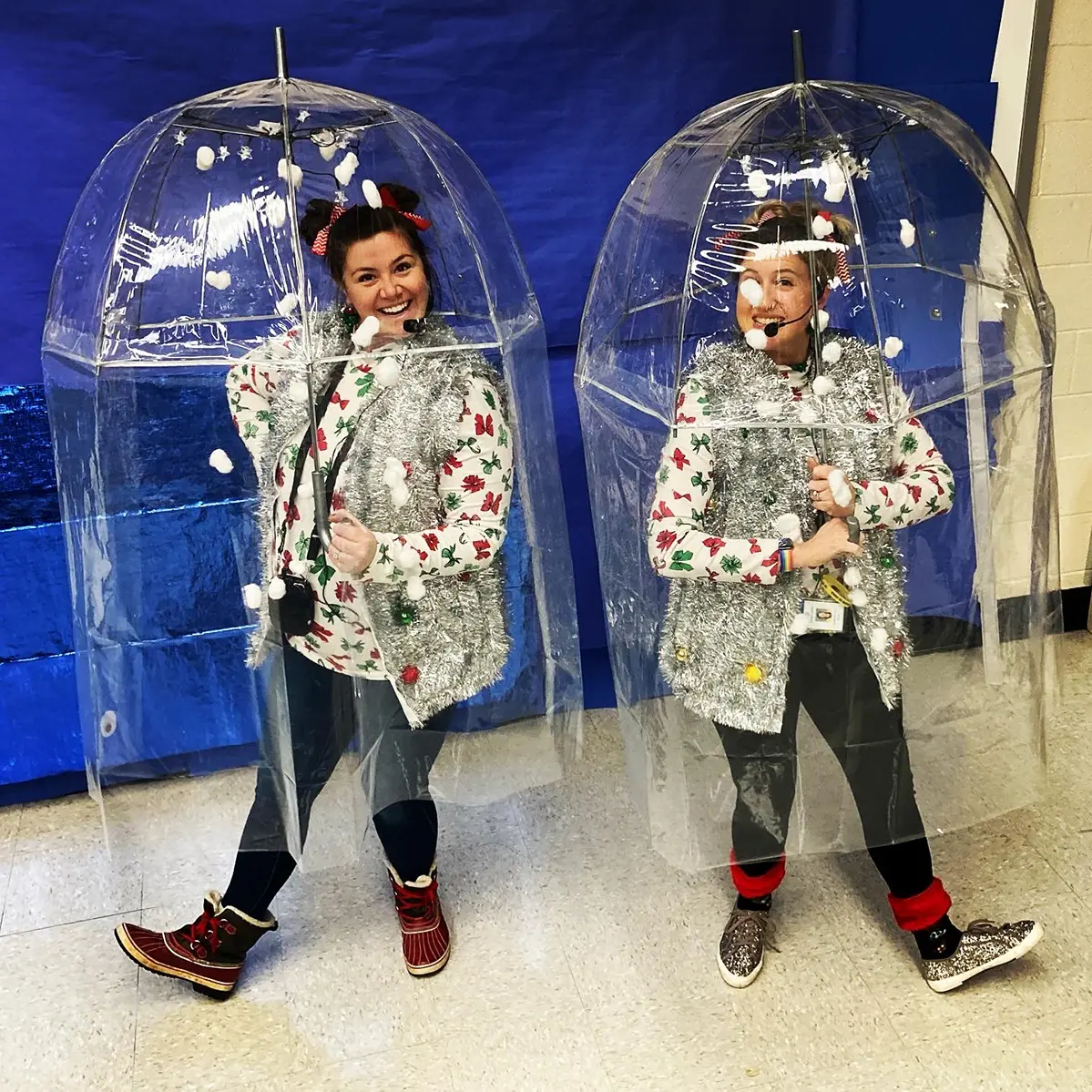

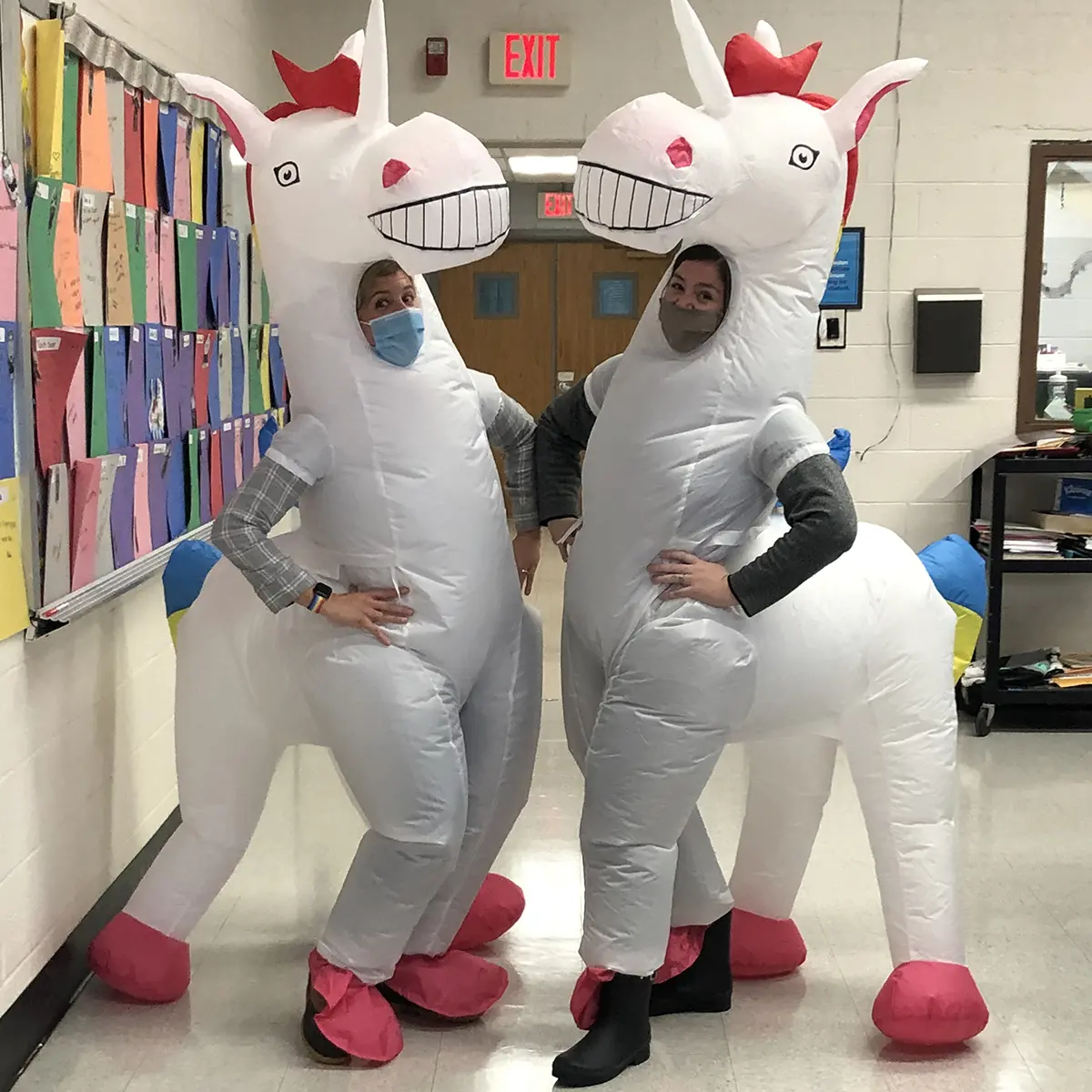

Silcott and fellow teacher Grace Sowers delight in bringing fun to their students, as Silcott’s camera roll illustrates.

Sometimes Sowers and Silcott — both Ohio State alumni — dress up as funny characters. Sometimes they stage little performances.

But all of the time, these middle school teachers have an important lesson for their students: Laughing at yourself is a good thing.

Karen Stansberry Beard ’83, ’89 MA, ’08 PhD, an associate professor of educational studies at Ohio State, has conducted research into how teachers fared during this period of upheaval. If teachers aren’t doing well, she reasons, students won’t do well.

“It’s like you’re asking educators to be social workers when they aren’t trained to be social workers or even counselors,” says Beard, who observed the domino effects of the pandemic on students, teachers and administrators. “While they were trying to engage children in the learning experience online, [teachers] were also very frustrated and taxed.”

Layer on top of the pandemic’s educational repercussions the social justice re-ignition sparked by the murder of George Floyd, which played out repeatedly online and on television while children were schooling from home. “The timing of the two forced children to reconcile injustice when it was at its most raw and they were at their most vulnerable” Beard says.

As was true everywhere, those two years were difficult at Shanahan Middle School, McDaniels says. Students lost hard-won daily habits, including social-emotional progress, which Beard describes as self-awareness and interpersonal skills. When the school returned to normal operations this past year, everyone had a lot of relearning to do. “For literally the first half of the year, we were reteaching kids how to do school,” the principal says.

Administrators created monthly mindfulness gatherings, and McDaniels and Assistant Principal Christina Zeller set up coffee makers in their offices so staff members could “fill their cups” literally and figuratively any time. McDaniels says he can’t overstate Silcott’s part in setting a cultural, emotional and mental tone for teachers and students.

“The way she has been able to maintain that positive spirit throughout all this and never shown a crack is just unbelievable,” he says. “She is one of those people, when you first meet her, you’re like, ‘There’s no way she can be this positive.’ But then you continue to meet with her and you’re like, ‘She doesn’t have the ability to be any other way.’”

The good stuff

Silcott and Sowers are goofy peas in a pod. They create intentionally awkward videos and social media posts to brighten standardized testing weeks, holidays, breaks, the occasional any day. Sometimes they set up an elaborate performance tableau at the school entrance and serenade students as they stream in, welcoming the groans, eye rolls and smiles they inspire.

“We’re so passionate about school morale and climate,” Sowers says. “We want to get kids to laugh at us and promote positivity.”

“If we lived through these past couple years, you’re gonna be OK for sure. You can do hard stuff.”

But it’s not just about the theatrics. Early in the pandemic, Silcott sent her students a heartfelt video message with her plan for what at-home choir would look like. “First and foremost, I miss you so much,” she tells them, seated at one of her pianos at home. “I miss our room. I miss how the sun would come in every time we would make music, no matter what time of day it was.”

She conveys that their spring concert — a cherished and anticipated event — has been canceled. She doesn’t mask her disappointment, but she also doesn’t linger. “I have a plan for each day of the week that I think will follow our idea of having choir always be a place where you are comfortable and letting your emotions out and loving music.”

With her students, she often reaches back to her own childhood. When a girl confided that a boy was bothering her on the bus, Silcott knew the feeling. “I remember the bus. I remember this boy who made fun of me because I didn’t run fast in middle school. He was so mean,” she says. “I try to make sure they know that it’s gonna be OK.”

The feeling of belonging in middle school choir is a core memory for Silcott — she can recall it instantaneously and arrives at work every day wanting to create that feeling for students. “Your inhibitions go away. You don’t have to care about what other people think,” she says. “You learn to be your own person and feel supported.

“It’s so cool that all different kinds of kids can be part of choir. You don’t have to have a certain ability level. You could be the star baseball player or the mathlete or the student council leader, and then you’re all together making music,” Silcott says.

She chooses music that students can project themselves into, lyrics that blend sadness with joy, beginnings with endings. During the hybrid school year, eighth graders singing “Let It Be” explored the heartbreak that inspired Paul McCartney’s writing. When he knew his band, his best friends, were breaking up, his mother assured him in a dream that it would be OK. The song’s message was deeply personal to McCartney, but it endures because it is universal.

That kind of thoughtful song selection almost certainly played into Silcott’s nomination for the Grammy Music Educator Award — the notice came in spring 2020, just after the world had turned upside down — but she still doesn’t know who submitted her name.

Though her middle schoolers love her for it, Silcott’s choice to teach them isn’t common, her former teacher says. It takes extra considerations to create successful experiences.

Unlike other Grammys, nominees submit interviews, videos and written answers and advance through stages of competition. (They also can be nominated multiple times.) After the shock subsided, Silcott saw the nomination as a gift. “I was home and not doing any in-person teaching, so I was like, ‘This is the perfect time to reflect,’” she says. “It was a good outlet. I had been teaching 18 years and I could look at how things had evolved, and I celebrated the good stuff.”

Because 2020 was complicated, the award was shelved for a year and nominees were invited to reapply in 2021. Silcott did, and she kept advancing in the competition. “I was like, ‘This is crazy!’ And then, I didn’t win this year, but through the process I was able to connect with the other finalists and celebrate the journey.” She revels in meeting these people who share her passion for music and teaching, who have fresh ideas and perspectives to share.

Of the publicity surrounding Silcott’s nomination, Apfelstadt says: “It’s probably made people in that community, in the larger Columbus area, understand that they’ve got a real jewel there. She’ll talk with her kids about that, too, because some of them will wonder, ‘Well, if you didn’t win, what’s the point?’ That’s a good lesson for them.”

Moving, advancing, trying

Silcott hands out sheet music for Shakira’s song “Try Everything,” from the “Zootopia” soundtrack. Shakira makes singing sound easy, something the sixth graders figure out quickly. Silcott plays the recording and they sing along “Carpool Karaoke” style. She talks through most of the song’s three minutes and 16 seconds, pointing out the soaring harmony, wondering what kind of band they could assemble for the class concert.

Then she cuts the recording and just the students’ voices, piano and sheet music are doing the lifting. It’s tricky. The music on the sheet doesn’t match what they heard on the recording. Silcott talks them through all of this, instructing them to trust the sheet music. They piece it together as a team, breaking down phrasing, then splitting into two groups to sing the melody and harmony.

I messed up tonight

I lost another fight

Lost to myself, but I’ll just start again

I keep falling down

I keep on hitting the ground

But I always get up now to see what’s next

Birds don’t just fly

They fall down and get up

Nobody learns without getting it wrong

Silcott bounds across the risers, singing melody, harmony, then melody again, her entire body conducting the students’ voices, holding their attention, which had seemed so gnat-like.

Learning the song is fast and slow — slow because even the word “I’ll” is difficult to sing in this song and will take repeated attempts to polish. Fast because Silcott keeps them thinking, moving, advancing, trying. Before class ends, they are running through the song coherently, in distinct parts. They are creating something in real time, and you can feel the joy.

The bell breaks the spell. The time has evaporated, and the singers are carried away on their chattering energy, out into the hallway and into the soup of middle school, a song in their hearts.

Silcott is quite deliberate when choosing songs for her students to sing or showcase. They must be ones the students can succeed at, but also songs that send a message, often of encouragement or inspiration.

Silcott-isms

Katie Silcott lives by a lot of good ideas. Here are some of them.

Marigolds

Silcott continues to find power in the message of “Find Your Marigold: The One Essential Rule for New Teachers,” a 2013 article by Jennifer Gonzalez. Marigolds, the flowers, shield other plants from harm and help them grow. Lesson: Find the people in your life who will do the same for you. Extra credit: Be one of those people.

Sunshine ratio

“For every one yucky thing, find two good things,” Silcott says. If something has gone totally haywire, acknowledge it, then think of two aspects of your life, your week, heck, your year that are going well. Lesson: Your negative business won’t disappear, but you can gain some perspective on it.

Buffalo vs. cows

There’s a leadership story about how cows and buffalo react differently to approaching storms. Cows run away as fast as possible. They avoid the storm, but they’re exhausted. Buffalo group and make a sort of plan to stand together through the storm. They have a tough time, but they are not exhausted by the end. Lesson: Learn to withstand hard stuff and you will become more resilient.