‘You give it all you have,’ says Dr. P

Inspired by family and faith, Patrice Palmer ’09, ’10 MSW is a nonprofit CEO, the National Social Worker of 2022 and a former inmate with one mission: breaking the cycle of self-abuse one soul at a time.

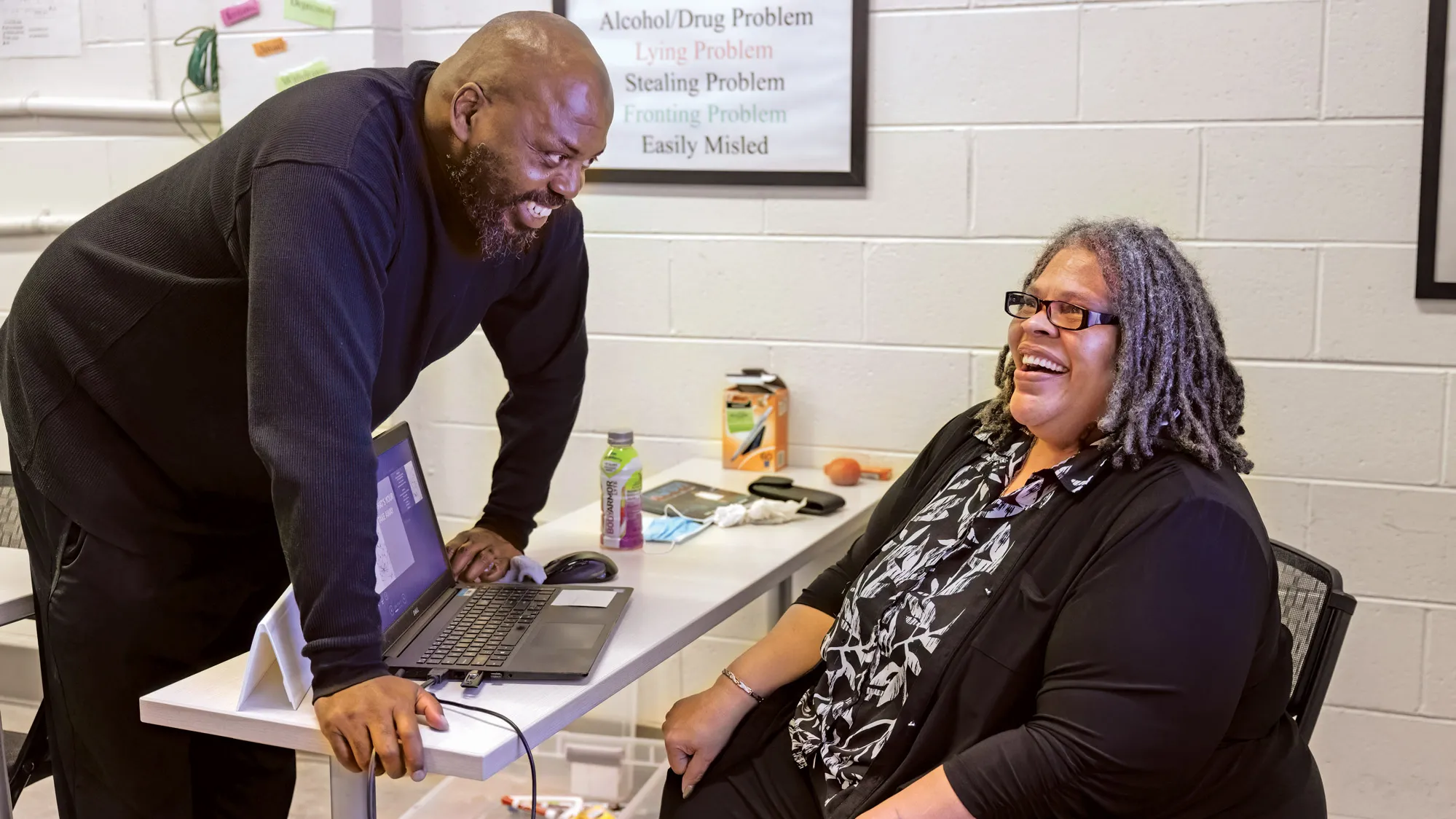

In a weeklong class that is part of the mayor’s EDGE (Empower Development by Gaining Employment) Program, Patrice Palmer teaches people to succeed after prison by finding their authentic selves.

Twice a year, Palmer leads one-week cohorts, sharing her own experience and expertise. She says it’s about “helping people to remember their past, embrace their present and envision their future.”

This class is one commitment in a jam-packed schedule that follows a particularly trying year: Palmer broke her wrist and battled COVID-19, then dealt with ensuing depression. But today, it seems like she hasn’t lost a step.

Palmer commands the room with charisma and raw authenticity. Her face is expressive, her voice electric. Under buzzing fluorescent lights, she speaks without a script — asking questions, absorbing people’s answers and riffing off them, constantly in motion even though she’s seated.

“You got to commit,” Palmer tells her students. “Accountability. Determination. It all starts with self-care, self-love. If you don’t love yourself, you won’t change. If you don’t feel worthy, whatcha gonna do?”

Bam! She slaps her palms together.

“Self-destruct!”

Palmer has walked this path herself. Former U.S. Sen. Rob Portman ’22 HON, who invited Palmer to be his guest at the 2020 State of the Union address, calls her “a shining example, a living embodiment that recovery is possible.”

“I have a criminal record longer than Cleveland Avenue,” Palmer tells the class. “I was Bonnie and Clyde all by myself. But since then, I’ve been to the White House. I spoke to congressional staff. I have two degrees from The Ohio State University.”

Palmer, who many call Dr. P, helps her students feel heard, and she closes her EDGE classes with a simple but sincere statement: “It has been my honor to serve you guys.”

People call her Dr. P, as she has a doctorate in divinity and theology. Faith is her foundation, she says.

Keeping track of her accomplishments and affiliations is daunting. She’s a member of Ohio State’s College of Social Work Alumni Hall of Fame. She was Franklin County’s 2018 Employee of the Year. She’s been honored by the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction, Cincinnati State Technical and Community College and many others.

All that recognition stems from meaningful contributions at both the macro and micro levels. Palmer has worked on initiatives for the city, county and state. Testifying before the full Ohio Senate, she helped get legislation passed to remove the criminal history question from public employment job applications.

That’s important because it had long been one roadblock for people trying to find good jobs that can help fuel better decision-making and a better life — and almost a million Ohioans have felony convictions. Include misdemeanor convictions and the number doubles.

Even as Palmer has gained allies among the powerful, she’s continued to make an impact in classrooms and by personally investing in people.

In the two years since retiring from her job as a reentry support specialist with Franklin County, Palmer has ramped up Chosen4Change, the nonprofit she co-founded in 2010. It’s a small organization, mostly run out of Palmer’s Canal Winchester home. She is CEO and has two part-time staffers, including daughter Ozsha’leek Palmer-Martin ’11.

But Chosen4Change accomplishes a lot because the woman at its center is a whirlwind.

“She doesn’t have a normal day,” says Ozsha’leek, who also works as a postmaster and real estate agent. “I would say a normal day is probably a plethora of things going on. You can’t really pinpoint. The way the wind is blowing is where we’re headed.”

Chosen4Change is one of six organizations partnering with the Ohio Governor’s Expedited Pardon Project, which accelerates the pardon application process for people with nonviolent felonies who’ve demonstrated reform in their lives.

“It helps to remove that scarlet letter so that people can get better jobs — sustainable jobs — and live in different places,” Palmer says.

Tom Jenkins came into the EDGE class without expecting much but finished it impressed by how much Palmer understands and cares. “She wants to work with you. She wants to see you succeed,” he says.

The project is close to Palmer’s heart, as she went through a tedious process to have her own record cleared by Gov. John Kasich ’74 in 2017, but it’s just one of her many professional endeavors. Under the banner of Chosen4Change, Palmer also has worked with RI International, a mental health crisis program.

Palmer’s approach has drawn support from philanthropists and officials alike. Buckeyes such as Jane Grote Abell ’88 and Tom Krouse of Donatos, and John Spayde ’94 and his companies are among them. Former Franklin County Commissioner Marilyn Brown, who knows Palmer from her work for the county and supported the effort to get her record cleared, admires her work with students.

“I saw it many times where she would be in a class with the women in jail,” Brown says. “She would start with a lesson, and somebody would have something they needed to say and work on. And Patrice would just take it and go with them wherever they needed. It was very impactful. People respond in a very positive way because they know they’re being listened to.”

Those responding today include Tom Jenkins, 51, who says he came into the class feeling hopeless.

“At first, I kept thinking, ‘Ah, it’s another one of these. It’s just someone hyped up to try to get some money,’” Jenkins says. “But no, that woman, she’s really out here. She advocates. She wants to work with you. She wants to see you succeed.”

Monique Smith, 26, says Palmer’s example helped her realize she, too, can overcome barriers and choose a new path.

“I got a home vibe from her, so I was able to let my hair down,” Smith says, comparing the feeling in Palmer’s class to good feng shui. “When she came in here, literally it just felt like you could talk to her about any and everything, no judgment, no nothing. She listens. I just love her spirit.”

After an hour, the first class departs, with students fist-bumping or shaking Palmer’s hand on their way out. A second group immediately arrives, and Palmer does it all again, drawing lessons from her life story with matter-of-fact sincerity and a fervor that reflects her background as an ordained minister.

At 5:20 p.m., after leading back-to-back classes, Palmer leans against her car outside the building, dabbing her damp forehead with a handkerchief.

“When you pour out so much from yourself for so many people, it makes you tired,” she says. She describes her effort to pull something from everyone in the classes, making sure those who aren’t speaking up are still heard.

“It’s draining,” she says. “I’m totally wiped out. You give all you have.”

Palmer and Marilyn Brown, collaborators and friends, meet at a Panera to plan their next project. “She has a way of connecting with people,” says the former county commissioner.

Palmer faced heavy challenges from an impossibly young age.

She grew up the Columbus neighborhood of Linden, the youngest of three children. Her mother died when Palmer was just 4 years old, and after that a family friend started sexually abusing her.

“That kind of shattered me, set me on the course of self-sabotage,” Palmer says.

Her family didn’t recognize her abuser’s impact because they interpreted it as grief. At age 9, she started drinking alcohol to cope with the pain. Soon after, she began using and selling drugs. At 13, she attempted suicide via overdose.

Her drug use would lead her to crack cocaine in the ’80s and “forgery, writing checks, stealing, whatever.” In 1989, that lifestyle led her to prison.

All Palmer learned during that first six-month term was “how to be a better criminal.” When she got out, she went right back to crime and substance use but stayed under the radar. Her relatives often stepped in to care for her four children.

“I began to deteriorate as an individual,” she remembers. “My stepmother would say, ‘You look like death on a lonely highway.’ In my mind, I was looking great. I didn’t see what they saw.”

After a decade, Palmer did a second prison stint, then a third. When a judge sentenced her to a fourth term in 2003, he said he wished he could send her away for life because he was tired of seeing her in court. She was humiliated.

Several eureka moments followed. First came a prayer on the morning her bus approached the facility. “The fog lifted, and I had an epiphany: The barbed wire is there to keep me out, not keep me in,” she says. “I went in with a different mindset.”

The sincere way Palmer listens encourages people to feel at ease, which is true in her social and professional lives. Here, she chats with Peggy Hardiman at church.

As she began to seriously pursue the prison’s rehabilitation programs, her brother visited. Normally he brought her kids along, but this time he refused. He said her children deserved better, and the family was cutting her off until she turned things around.

“For the first time, I thought about what this looks like to them,” Palmer says. “I was devastated.”

She went back to her cell, got on her knees and offered up a tearful cry for help. “That was my moment of surrender,” she says, recounting how she asked God to empower her to make the life change she desperately needed.

Upon her release later that year, Palmer started over. She entered an inpatient treatment program in Cincinnati, got two jobs and enrolled at Cincinnati State Technical and Community College. In 2007, she was accepted at Ohio State and awarded a College of Social Work scholarship. She participated in the ACCESS program, which assists parents pursuing their education, and landed jobs with University Libraries and Recreational Sports.

While pursuing her master’s degree, Palmer interned at the nonprofit NISRE (Nothing Into Something Real Estate), which focuses on helping people make positive changes; she eventually joined the staff. Later, while working at Chillicothe Correctional Institution, Palmer founded the therapeutic community Conquest. In 2015, she was hired by Franklin County’s Office of Homeland Security & Justice Programs, where she developed Pathways for Women’s Healthy Living, an award-winning program that reduced the recidivism rate for participants by more than 70 percentage points.

In her role as a social justice advocate, Palmer worked closely with Roni Burkes of the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction.

“I look to her for so much,” says Burkes, a former warden of the Ohio Reformatory for Women in Marysville. “Her insight about the things we should offer and the opportunities for women has been really, really invaluable.”

They serve together on the 21-member Ohio Ex-Offender Reentry Coalition, a group of lawmakers and cabinet-level officials who brainstorm ways to reintegrate offenders into society. Palmer is the only “civilian” member, and she’s there to bring her experience to the conversation.

Burkes often invites Palmer to speak to groups of incarcerated women and notices “literally not a dry eye in the room, including staff.”

Other times, she’s reached out to Palmer for help in individual situations. When a former inmate was seeing all her rental applications denied, Palmer found her family a home and organized donations of housewares and appliances.

“Dr. Palmer is the epitome of redemption and transformation. Her compassion for humanity’s restoration is driven by God’s grace and divine purpose for her life,” says Bishop Sherman S. Watkins, who leads her church, Higher Ground Always Abounding Assemblies. “She is a blessing to those she encounters, and it is my honor to counsel and cover her in prayer for over 40 years.”

Similarly, Frank Carl, lead pastor at Genoa Church in Westerville, recounts how he met Palmer by chance at the county courthouse while seeking to reactivate utilities for a family he’d been serving. When he explained the situation, “Dr. Palmer smacked her hand down on the table and said, ‘Glory to God, I’m now your guardian angel.’” She put in a call and had the water and electricity turned back on within 30 minutes, he says.

Palmer, who belongs to Higher Ground Always Abounding Assemblies and became an ordained elder of ministry in 2014, has since preached several times at Genoa. At one memorable women’s conference there, she threw coins on the floor and encouraged those seeking change in their lives to take them home as a reminder.

Carl says his church savors Palmer’s visits and has worked with Chosen4Change on projects such as an annual Christmas event for families in need. Palmer even provided helpful counsel to Carl’s daughter.

As for Palmer’s own family, it took time for relationships to mend.

“Nobody ever gave up on her, but people got tired of excuses and the repetitive nature of that behavior,” says one of her sons, Navy Cmdr. Brandon Palmer. “As a family, we have to hold each other accountable. Accountable doesn’t mean we care less about you.

“Our love for her was critical in her transformation,” he says, “and that love is stronger today than ever before. She is our unsung hero.”

Nothing about Palmer’s transformation has been easy. “I still cry sometimes when I think or talk about it,” she says. “My kids — at that time, I was getting high or in jail — damn, I should have been there. All I got is pictures. I want memories.”

As evidence of her transformation piled up — she’s now been sober 21 years — Palmer rebuilt trust with her children. She’s writing a book that will include her kids’ input about how her choices affected them.

“She turned the bad things that she experienced in life into good,” says Ozsha’leek. “I think her grandkids are getting the best version of her.”

A week after teaching the EDGE course, Palmer is again holding court at an intimate gathering, this time at the “I Am Not a Victim Anymore” conference in Columbus. She preaches from a wooden lectern, often stepping out from behind it as if she can’t be contained.

The constant motion is back. So is the impassioned telling of her life story. This time, Palmer recounts the sexual abuse she suffered as a child and its psychological effects.

At the “I Am Not a Victim Anymore” event, Palmer shared her story of being abused. Because of fear and guilt, she kept it secret for decades, using it as “my excuse to use drugs and not become my best self,” she says. “But now, I’m not afraid to talk about anything.”

“I was too busy trying to see if somebody else was about to hurt me,” she tells a group of women, mostly about her age. They listen with rapt attention.

Palmer has realized that presenting her life from this angle is one way she can empower more people. For the past year, she’s been thinking about how to expand her reach, ever since she found herself unexpectedly in one of the darkest phases of her life.

In October 2022, a few months after Palmer was named National Social Worker of the Year, she fell at home and broke her wrist. On her first day recovering at a rehab center, she caught COVID. She spent the next two weeks in isolation at the facility, an experience that made her feel like she was back in jail.

In quarantine, Palmer considered her future, sketching out ideas for new programming. A lot of people her age would be slowing down. But in that rehab center, Palmer decided she wanted to widen the scope of her work and find new ways to serve. In particular, she decided to do more to reconnect and rebuild families after trauma.

But as Palmer recovered, depression got in the way. Her broken wrist meant she couldn’t drive. She had to curtail her community involvement. Her family grew concerned.

“I went through about two months of total depression because I just felt useless,” she says.

She’s now back up to about 75%, she says. She found aid for a weary soul through a daily morning routine of prayer, meditation and journaling followed by swimming and working out at a gym. But nothing has been as essential as family.

Palmer started publicly sharing her story of being sexually abused after she realized that many people who have similarly suffered could use her help and support finding the hope that they can reclaim their lives.

“My children and grandchildren are the most important thing to me,” she says. “Their love, respect and trust are the heart of who I am and the work I do.”

Palmer is making time to paint, as she has for years been a trainer with PeaceLove, created by Jeff Sparr ’85. She has a plan to introduce the therapeutic art program at the Franklin County Crisis Care Center once it opens, as well as in several local schools and universities.

More projects are in the queue, helping Palmer stay motivated. She recently collaborated with Gretchen Clark-Hammond ’00 MSW, ’11 PhD on a new curriculum module for peer support and facilitator training for the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services.

Clark-Hammond wrote Palmer’s recommendation for the College of Social Work Hall of Fame and also has worked as a lecturer for the college. She recently saw Palmer deliver an electric keynote address to several hundred people at the Ohio Recovery Housing Conference. “It was inspirational — people were standing up, moved by the spirit of her message,” Clark-Hammond says.

Such is the vibe at the “I Am Not a Victim Anymore” conference as Palmer dabs her brow and connects the dots between guilt, shame, confusion and the destructive behavior that derailed her life for so long. Watching her attempt to guide others toward peace of mind, it’s easy to see why Clark-Hammond says Palmer is making the most of her life.

“At the end of the day,” Palmer says, “our work is amazing because we get to use the principles and foundation of social work to restore the value, the dignity and the worth of a person.

“Every day, I get to help somebody. Every day, I get to give somebody hope. Every single day, I see miracles.”