Dodging thieves and taking on gender discrimination

Ellen Mosley-Thompson and Lonnie Thompson reflect on the value of personal identity, facing your fears and forging paths for others.

By Laura Arenschield

Ellen reclaims her maiden name — for keeps

I arrived at Ohio State as “Ellen M. Thompson,” and my first couple of scientific papers were published under that name, too. But when Lonnie and I started going to professional conferences, I had a wakeup call. We went to the same conference, for which I had registered as “Ellen M. Thompson.” Lonnie and I went to the registration table, and he went first. When I asked for my name tag, they said, “Oh, honey, you’re at the wrong table. The table for accompanying spouses is down that way.” And that infuriated me. I was nice to the lady, but inside I was on fire. And I said, “No, I’m sorry, but I’m actually a registrant. Could you please look up my name so I can get my materials?” She felt badly, but that was just the way it was then: The assumption was if a woman was with a man, the man was the one attending the conference and the woman was just along for the trip. I came back and I changed my name to “Ellen Mosley-Thompson” on everything. I never published another paper or registered for another conference without “Mosley” again.

Lonnie weathers being unplugged in the 1970s

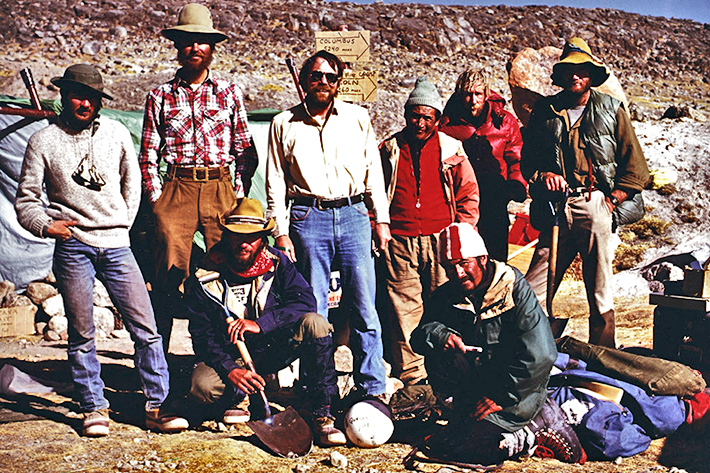

In 1976, there was no GPS, no maps into the area of the Quelccaya ice cap. There was a road that ended near the mountain, and the police told us: “If you go beyond here, we can’t do anything for you: That’s where the robbers and murderers go.” It was a wild place. We left the end of the road and walked for two days to get to the ice cap. We took three shallow ice cores, and you could see the annual dust record was perfectly preserved on the summit. But there was no communication, so we’d made arrangements with our truck driver to come to the end of the road on a certain day months in the future. When we came out on that day, the driver was nowhere to be seen. One of arrieros who was helping our team transport equipment lived in a hut nearby, so he and I went down to his home. Because of robbers along the route in the evening, we waited until the middle of the night to go the rest of the way down the mountain on horseback, carrying guns to protect us. We found the truck driver and had him come back to help us get the rest of the team and the ice core samples down the mountain, too. It was a different world.

Ellen advocates for the women who follow her

In 1985, I led a team of six to the Siple research station in Antarctica. It was a turnaround flight, meaning conditions weren’t good for landing and we stopped only for fuel. No one could exit the plane. It was an excruciating 10 or 11 hours. In those days, the bathroom facilities on the C-130 transport planes we used were a urinal in the front of a plane with a curtain around it and an open bucket in the back. I was the only woman on the plane. Since I couldn’t climb up on the urinal, I had no suitable bathroom options for the whole flight. I voiced my view that the facilities were not amenable for women, and that ticked off the load master who told me, “Sorry lady, you just have to light a candle and pray [that you don’t need a bathroom].” That was the way things worked in Antarctica then. But within a few years, I was put on the advisory board for the Division of Polar Programs at the National Science Foundation, and there I had a voice. The next year, I was promoted to the position of board chair. Within two years, we had a portable toilet module (or head module, as they called it in Navy lingo) at the back of the plane that anyone could use in private. I saw making things easier for future female researchers as part of my job. That’s why I was so particular about my deportment and made sure I never did anything to make it harder for the women who would follow me.

Dale Gelter ’89 built decades of safety and service at Don Scott Field, mentoring crews and tending details few travelers ever see

Linda Kass ’78 MA didn’t plan to be a novelist, bookstore owner and community leader. She just followed her curiosity—and the stories that shaped her.

Sister M. Xavier Schulze ’11 discovered life was more than basketball while at Ohio State. Today, she lives with total commitment — faith, love and joy in full measure.