Everybody loves Archie

Archie Griffin ’76 could have used his football fame to be anything. What he chose to be: himself, a Buckeye at heart. And that’s why we still adore him 50 years after he won his first Heisman.

(Photo by Jodi Miller)

Likewise, Griffin’s off-field actions have made him known for more than football. They’ve occurred daily, big and small, all rooted in values of decency and respect for others. “His humanity is his defining characteristic,” Trethewey says.

Griffin is more than a trophy, statue or jersey number to Buckeyes. “What he stands for is a real person,” says Cornelius Green, his college roommate and the starting quarterback on their four Big Ten championship teams together. “Archie is loyal, honest, humble. That’s what Ohio State loves.”

Diante Griffin, now in his third year at Ohio State, grew to appreciate that by watching his grandfather always treat people, including strangers, with patience and kindness, whether in public or not. “How I carry myself is really passed down through him,” says the Ohio State cornerback and seventh Griffin family member to play for the Buckeyes. “How can you go 50 years and still be thought of as a great person? Everybody who talks about him—whether they know him personally or came across him once or twice—all have great things to say about him as a man. It’s astonishing.”

Not that grandpa is ever impressed with himself. To Archie Griffin, everything is about others, about teamwork. “You can’t do it alone,” he says.

The joy on young faces still moves Griffin five decades later. “It was something to behold,” he says.

Such is Griffin’s sweet memory of patients at then-Children’s Hospital just south of downtown being thrilled to see him and other Ohio State players visit each week during football season. “I found out then that I loved paying forward,” he says. “I wanted to do things to help others.”

Griffin heard his coach, Woody Hayes, preach daily that “you can’t pay people back for being good to you, but you can always pay forward.”

The concept dates to a 317 B.C. mention in a Greek play, and the ancient idea has since had many cultural references, including in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1841 essay, “Compensation.” That’s the one Hayes paraphrased when he popularized paying forward. “Not only did Woody talk about it,” Griffin says, “he did it. He lived it.”

For example: making Griffin and other players get into Hayes’ Chevrolet El Camino after every Thursday practice so he could drive them to the hospital. There, a secret entrance kept their good deed from public view.

Such actions became an ethos lived by Griffin. He paid forward often as an Ohio State employee for nearly 40 years and, now retired, remains a committed and engaged alum. His lifelong university advocacy spilled into supporting charity and special causes and spending time on business and organization boards. “Ohio State really gave me an opportunity to have a platform to serve people,” Griffin says.

Ohio State student-athletes have benefited from his Archie Griffin Scholarship Fund, established in 2002 to aid undergraduates in Olympic sports. In 2018, he and his wife, Bonita, founded the Archie and Bonita Griffin Master of Sport Coaching Scholarship, annually awarding pursuers of a sports coaching degree in the College of Education and Human Ecology.

“I wanted to make sure these young people have the opportunity to get a college education, same as I did,” Griffin says. “I didn’t go to college just to play football. Football was my vehicle to get my education.”

Archie Griffin shows a replica of one of his two Heisman Trophies to sousaphone player Sean Bauman ’24 and other members of the Ohio State Marching Band. “When I look at this, I think of all the guys I played with,” Griffin says. (Photo by Jodi Miller)

Griffin graduated from Ohio State a quarter early with a bachelor’s in industrial relations, which he says made his parents prouder than his two Heismans did. Margaret and James Griffin Sr. never went to college, but all eight of their children earned degrees from athletic scholarships.

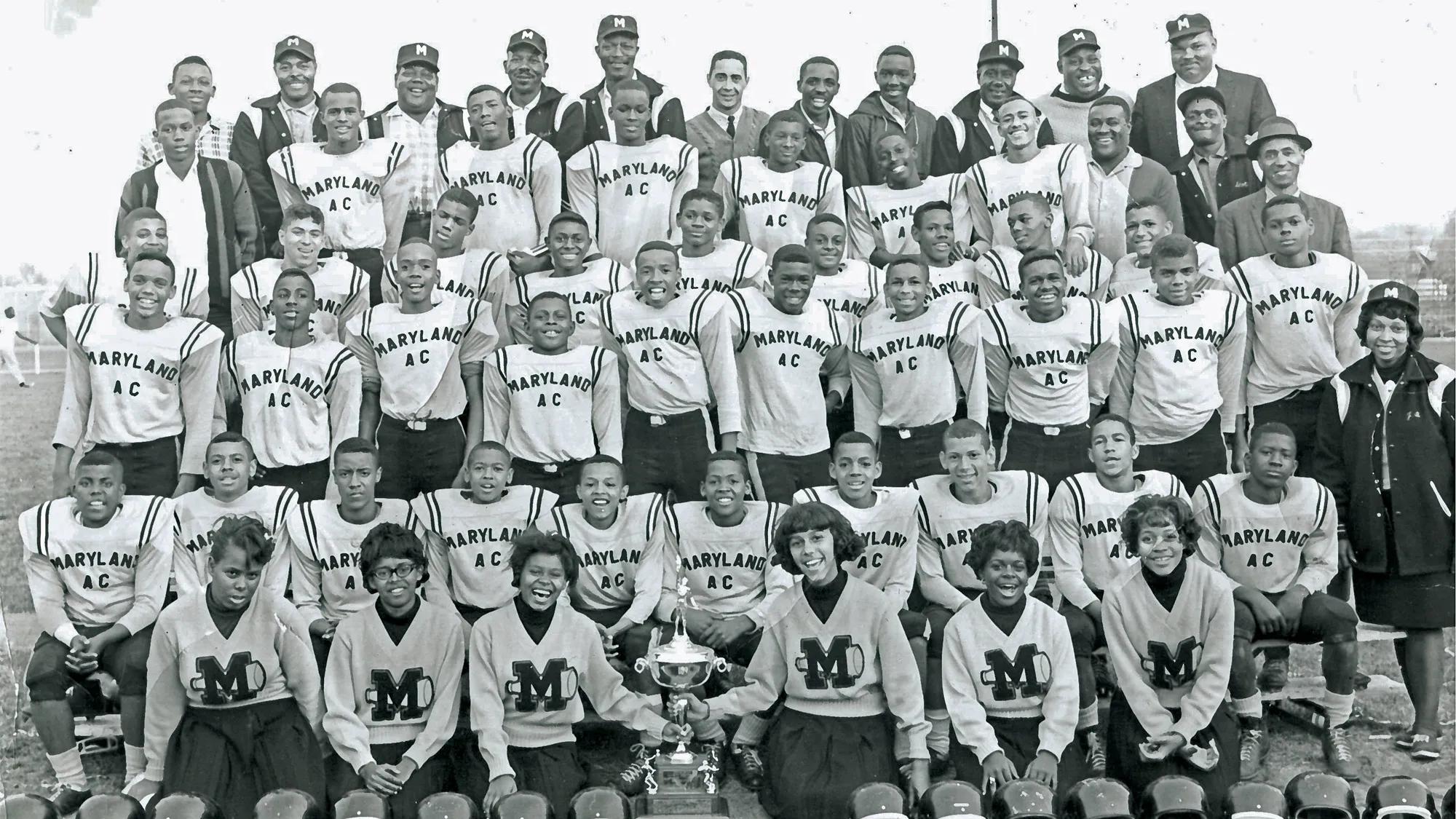

“My parents felt an education would be the best way for us to have success in life,” Griffin says. “They wanted their kids to have a better situation than they did. They were always trying to move us forward.”

The Griffins moved to Columbus from West Virginia, where James had worked as a coal miner, shortly before middle-child Archie was born. Dad worked for Columbus City Sanitation and Ohio Malleable Steel Casting Co. and did janitorial jobs—all three at the same time, sunrise to midnight. Mom ran a small market on Rich Street located inside the front of their first Columbus home on the Near East Side.

Besides the market, the first floor rented by the Griffins had a kitchen, a room where the family watched TV and parents slept, and a bedroom where the kids shared two sets of bunk beds. “There were a lot of foot battles with my brothers at night—a lot of closeness,” Archie says.

The Griffins eventually moved to Linden, across Interstate 71 from Ohio State and a little north, then to Berwick, about a 15-minute drive southeast of campus, before Archie’s first year at Eastmoor High School (now Academy). Each stop, the family felt swaddled by neighborhood togetherness. “Everything wasn’t great all the time, but everybody helped each other out,” Griffin says. “That’s the type of community we had.”

Griffin says he found the same closeness at Ohio State, and not just in football. Professors, classmates and Hayes supported his academic goals. Buckeyes look outward, not inward. “That’s what makes this place special,” he says.

Hayes fostered teamwork in football, imploring everyone to hold one another accountable for their specific responsibilities. Teammates saw how Griffin thrived in that tight atmosphere so similar to how he was raised. “He had the attitude of being a servant leader, and he has always had it—that spirit of a champion,” says Randy Gradishar ’74, a two-time All-America linebacker and member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Green recalls being a homesick freshman, anxious in unfamiliar Columbus, unsettled on a predominantly white campus after growing up in a Black neighborhood in Washington, D.C. His roommate and teammate helped.

“Archie would take me to his parents’ house for Sunday dinner,” recalls Green (who spelled his name “Greene” during his time on campus but chose to drop that last e). “His mom would call my mom, and she’d be like a surrogate mom. His father stepped in and became a dad for me. He said, ‘We’ve got seven boys; eight won’t be a problem.’ Archie added me to his family.”

The idea of family and togetherness never stopped growing for Griffin.

“My path,” he says, “has been surrounded by community.”

Quickness, balance and peripheral vision made Griffin one of college football’s all-time greatest running backs. He doesn’t pinpoint a particular play or game for his fame. “I don’t know that I really ever had a ‘Heisman moment,’” he says. “When you look at the reasons that I won the Heisman, I think most people say it was my consistency.”

Griffin ran for 100 yards in an NCAA-record 31 consecutive games, and such dependability also defines his off-field self. Buckeyes see reliability in how he lives privately and handles public demands. “It’s not like there’s two different Archies—there’s one Archie,” Trethewey says.

Green saw it on Sunday mornings after his Ohio State games. Each week, he wanted to sleep in, only to see roommate Griffin up at 7 a.m., putting on his church clothes. “Next thing you know, I’m getting up and going to church with Archie,” he says. “My whole life changed. I became a spiritual person. I owe that to how he lived.”

Griffin’s encouragement led Green and other Ohio State teammates to join the Fellowship of Christian Athletes. “We’d meet once a week and study the Bible,” Gradishar says. “Archie was very, very influential in my life, pointing me in that direction.”

Faith remains a cornerstone of Griffin’s life. Every day, he prays and reads a Bible verse on a cellphone app. “It keeps me focused,” he says, “and gives me something to think about all the time.”

Green thinks often about how Griffin—while winning his second Heisman—voted for him as Ohio State’s most valuable player. That broke the team’s tied ballot, leading to Green being awarded the Silver Football trophy as the Big Ten Conference’s MVP.

“I’m forever known for that, and it’s because of Archie’s vote,” Green says. “It meant the world to me. That shows the greatness of him.”

Griffin still says he voted for Green because the quarterback was the one player the team couldn’t afford to lose in ’75. To him, it was a simple decision: Do the right thing.

“Archie has strong principles,” Trethewey says. “He doesn’t have to remind himself what they are because he lives them all the time. He doesn’t tell you how to live your life; he just demonstrates it.”

Griffin says he’s never been one to talk much, which aligns with Eastmoor High classmates’ memories of him as a shy teenager. “Oh my goodness, you couldn’t get a word out of him,” Carla Curtis says.

Curtis was reacquainted with Griffin years after high school when she moved back to Columbus for an Ohio State faculty position in the College of Social Work, where she’s associate professor emeritus. “He was still very humble, unassuming,” Curtis says. “I am very encouraged, especially in these days and times, that an individual who is as accomplished and who has experienced as much in this world as he has remains approachable.

“Archie’s ego has never been the biggest part of who he is. It’s the man, the person and the quality of the character. The recognitions make his name bigger than life, but he remains committed to what he sees as his calling. As someone raised in a community and who has done well, he intends to give back to that community.”

Griffin credits Ohio State’s caring community for fitting his post-football aspirations after a seven-season NFL career with the Cincinnati Bengals. In 1984, Griffin joined the university’s human resources department (then personnel services), moved a year later to the Department of Athletics—staying 19 years in various director roles—and retired in 2017 as a special advisor in the Office of Advancement.

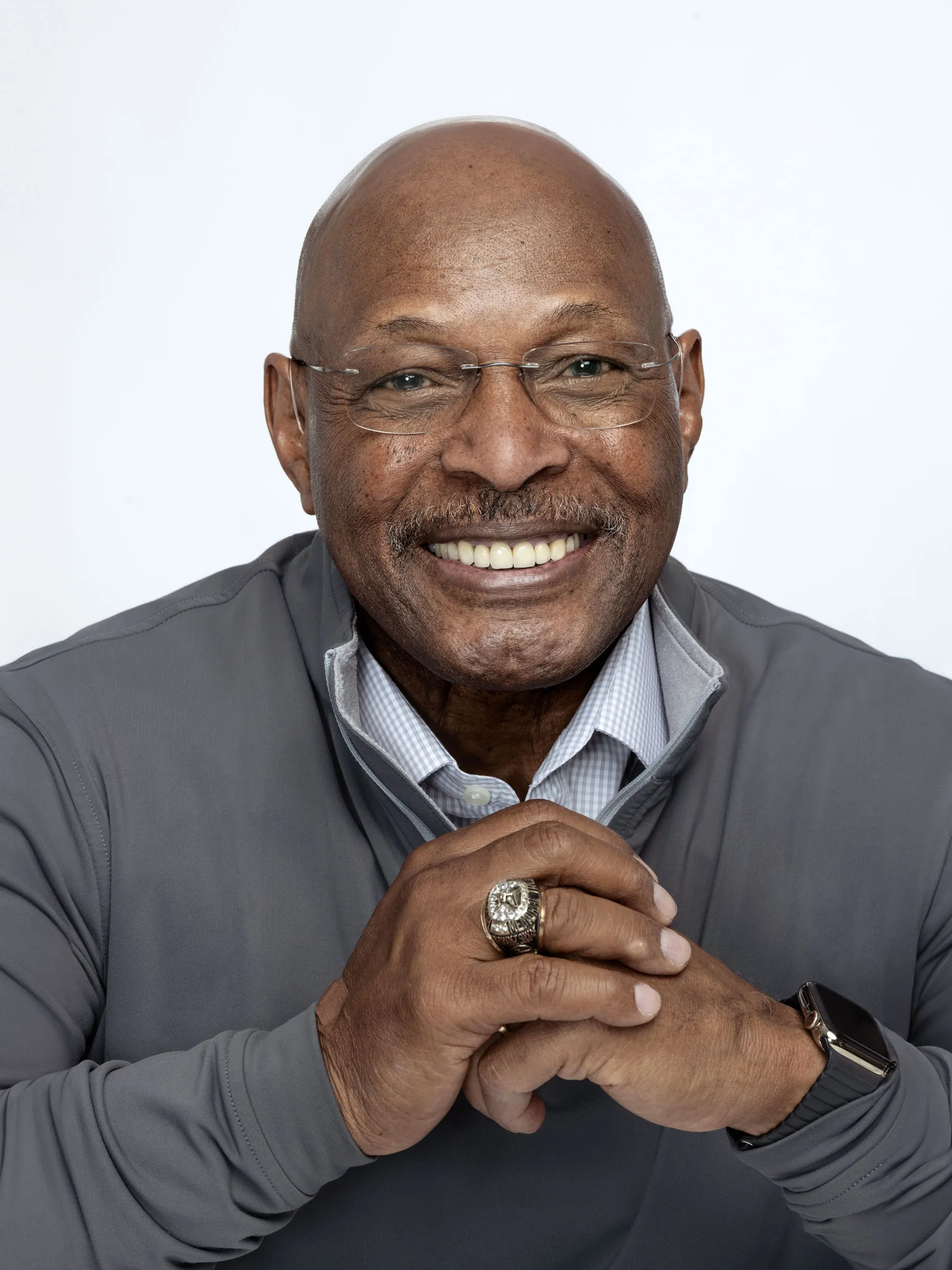

Griffin also served as president and CEO of the alumni association for 11½ years, a role in which he helped set up scholarships, mobilized alumni fundraising and created offices for career management and volunteer relations. “That’s the best job I ever had,” Griffin says. “I enjoyed getting out, being among the alumni, and enjoyed the people I worked with. We had a fabulous team. We did really, really great work and impacted the lives of our alumni, and that was very, very important to me.”

In 2012, Griffin guided the alumni association’s transition from a dues-paying membership model to one in which all graduates are members. The switch required a membership vote, bylaw change and move from independence to integration with the university.

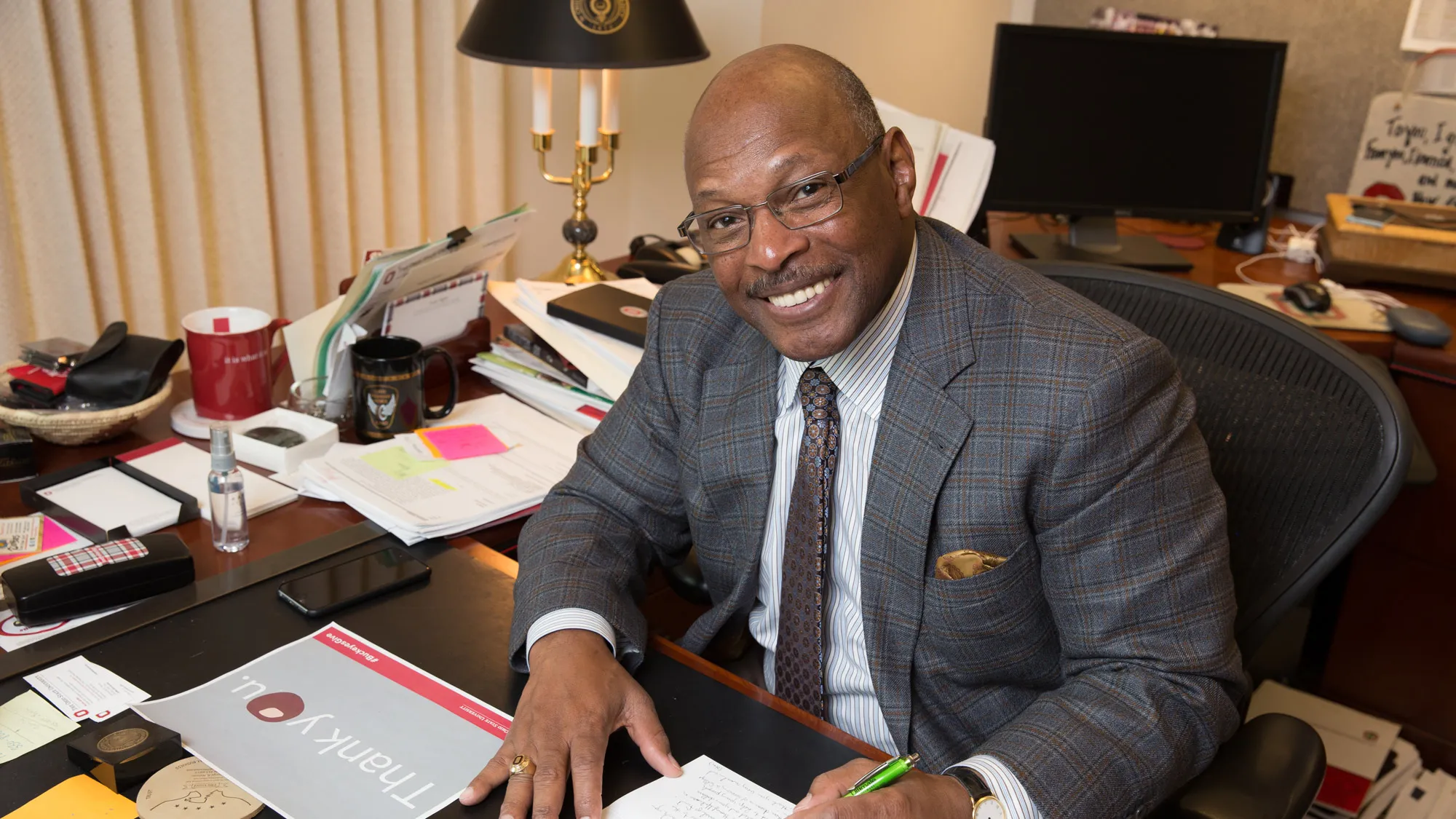

Griffin served as president and CEO of the alumni association from 2004 to 2015. “That’s the best job I ever had,” he says. “I enjoyed getting out, being among the alumni, and enjoyed the people I worked with.” (Photo by Kevin Fitzsimons)

“He navigated that supremely well,” says Shockey, who served as alumni association treasurer and alumni advisory council board member during her days working with Griffin. “He always asked the right questions. It never felt like he was pushing for something, but instead he let it evolve as organically as it could. Archie was really the catalyst for a lot of the right relationships. I don’t think anybody else could have done that other than Archie because of who he was, what he meant to the university and what the university meant to him.”

There was an unwritten rule known among alumni association employees during Griffin’s leadership. “It was whispered to me that one thing Archie doesn’t like is cursing,” Trethewey says. “That set a tone of mutual respect, a kind of gentility that kept people more harmonious.”

Griffin did like hearing others express opinions, sometimes encouraging participation by sitting near the back of rooms during meetings. He was known as a good listener, curious to learn. “He would never start a conversation by talking about himself,” Shockey says. “It was always, ‘How are you? What have you been doing?’”

Griffin says he learned from Hayes that leadership begins with caring. You win with people, and that starts one relationship at a time.

“One person can make a difference,” Griffin says, “if you have a series of people making a difference.”

A quiet van full of a half-dozen alumni association employees, including Griffin and Trethewey, travels through the desert night of Jan. 8, 2007. They’re returning to a hotel from a nightmarish BCS National Championship game in Glendale, Arizona, where Florida has defeated the Buckeyes 41-14.

“It’s late, and nobody’s happy,” Trethewey recalls.

Griffin asks the van’s driver to pull into an In-N-Out Burger. “Archie turns to us,” Trethewey says. “He says: ‘No matter how the game turned out, we’re going to finish this day like we should—together.’ And into the restaurant we go.”

Coincidentally, Sandy Slomin ’71 and about 50 other Ohio State fans are inside when the doors open. Hanging heads shoot up. “Here comes the man,” Slomin recalls. “The mood suddenly shifted.”

Griffin buys burgers and fries for strangers in scarlet and gray. He doesn’t make any loud, grand proclamations, but instead walks among the fans.

“He was talking one-on-one to people,” Slomin says. “The restaurant became the happiest, joyous place because Archie was there, doing his normal Archie things. He turned frowns upside down.

“Who else could do that, really, except Archie Griffin.”

Slomin first met Griffin in 2004 at the Ohio State University Golf Club when he was honorary chairman for a charity tournament. She handed him photos of her nephew, explaining he had cerebral palsy and considered Griffin his “goal model.”

Slomin quickly reached to take back the photos, thinking Griffin only intended a glance, but he stopped her, saying he wanted to take a closer look. When Griffin began slowly going through the photos, Slomin recalls: “An arrow went through my heart that this guy could be so sincere.”

Later that day, Griffin called Slomin to thank her for attending the tournament, sparking a friendship. Respect for his unwavering decency led her to donate the funds that created the Archie and Bonita Griffin Master of Sport Coaching Scholarship.

“You see him at all these functions, and he never varies,” Slomin says. “He’s just simply Archie. It’s not a persona. He is who we see.”

Griffin is relatable, standing 5 feet, 8 inches, about the average height of an American male. He says his normal size allows him to sometimes blend into a crowd, especially at his winter home in Sarasota, Florida.

From April through December, Griffin lives in the Columbus suburb of Westerville. He’s a regular at Ohio State games and often spotted around Central Ohio, where his hometown roots keep him grounded.

“I cherish my friends here,” Griffin says. “These are the folks I grew up with. They knew me when. They treat me like they’ve always treated me. No different. That’s the way I want it.

“I’m fortunate. I’m part of the Columbus family, part of The Ohio State University family. It’s all part of me. That’s special.”

Understanding the power of that relationship is why Griffin constantly credits his teammates and coaches for his winning two Heismans, why he remains committed to using that fame for good, and why he’s forever gracious when faced with the honor’s demands.

“Hey Archie, can you sign this?”

“Arch! Arch! Look over here!”

Griffin became historically known as a football player, but we now know him on a first-name basis because of what Archie the person did with his prestige, and how. To Buckeyes, he’s real, not a trophy, just as Griffin sees more than himself when he looks at the Heisman.

He sees us.

Together.

“Winning the Heisman at Ohio State,” he says, “it really belongs to everybody.”

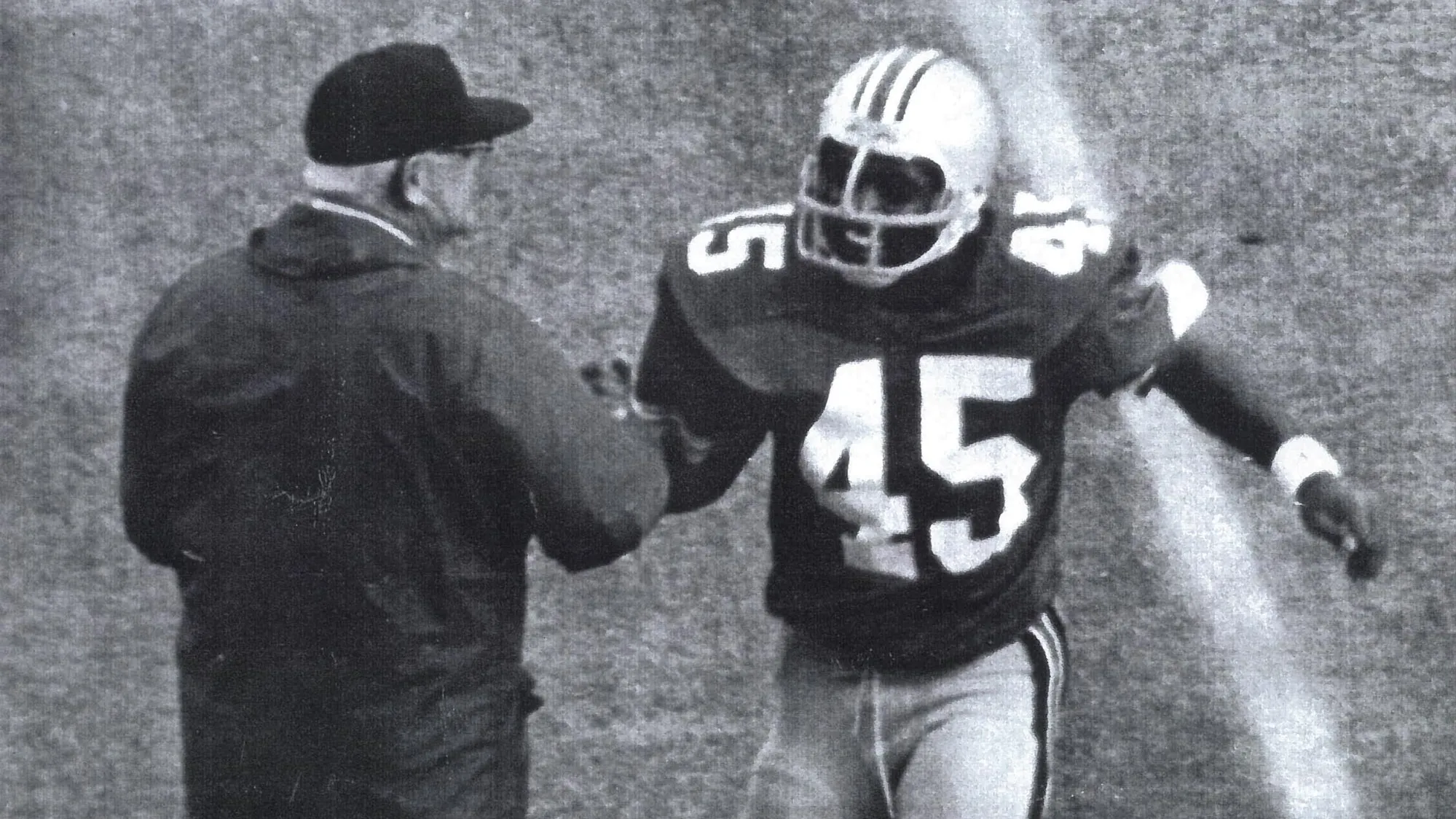

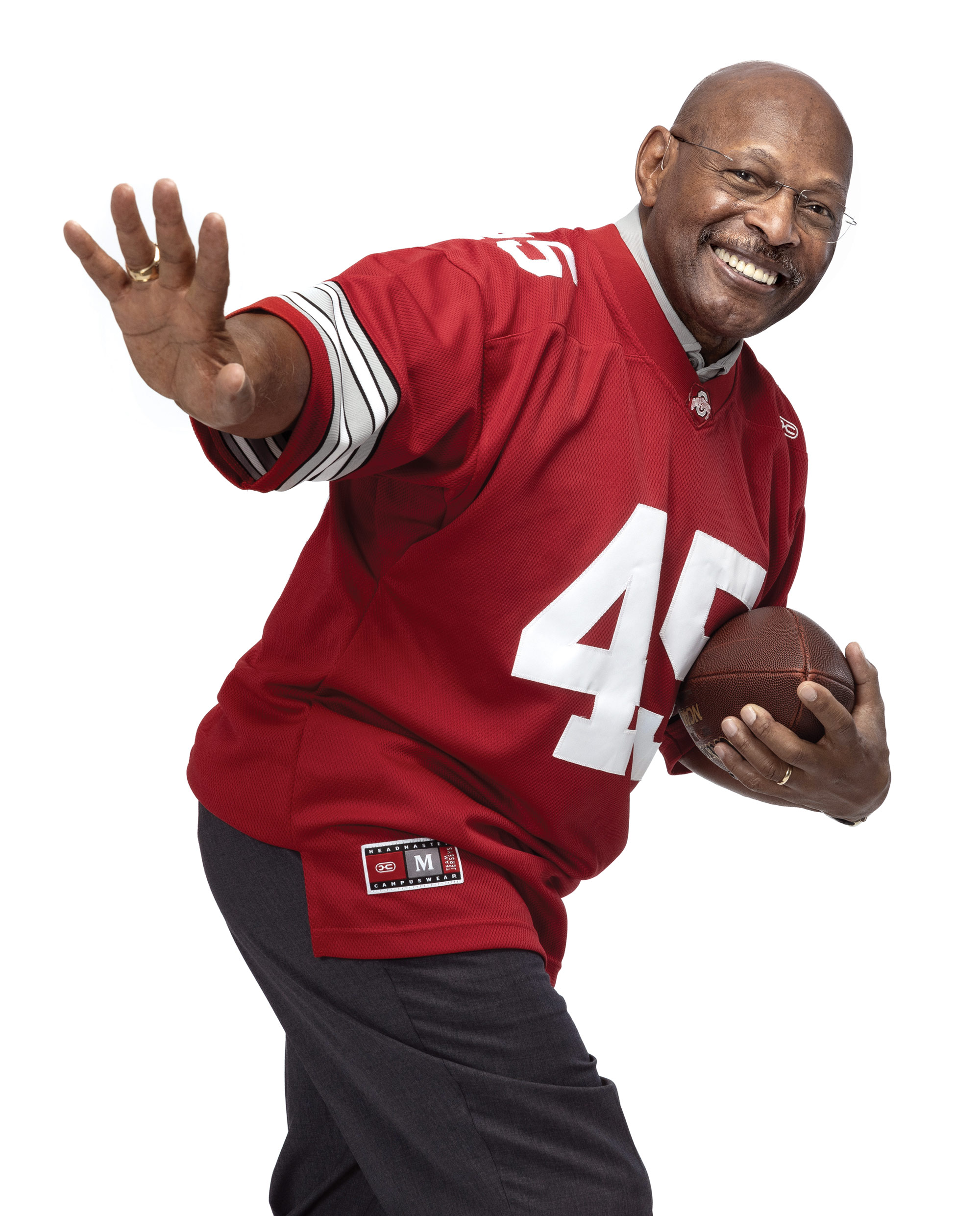

The man wearing a scarlet No. 45 Ohio State jersey is holding a football. There’s gray in his mustache, hearing aids in his ears, an earnest childlike look on his face. As always, he’s accommodating. “Whatever you need,” he tells the photographer.

Unprompted, the beloved Buckeye shifts his legs, left one behind the other, tucks the ball to his chest, and stretches out his right arm. The Heisman Trophy has come to life. Archie Griffin smiles.

“That’s pretty good,” he says, “for a 70-year-old man.”

See Archie in bronze (and in person)

Ohio State’s version of the Archie Griffin Rose Bowl lives on the north side of Ohio Stadium, and Tuttle Park Place, the road east of the ’Shoe, has a new honorary name: “Archie Griffin Drive.” This year’s Homecoming parade, meanwhile, offers an opportunity to see Griffin in person. The two-time Heisman winner will serve as the grand marshal, leading the Oct. 25 procession along its route through campus.