The inspiring courage of Dr. Christina Knight

Serving in Navajo Nation, this openhearted young doctor has pushed through hardship and self-doubt, strengthening her resolve to provide the kind of advocacy that changed her own life.

Listen to this story

Hear Senior Writer Todd Jones tell Dr. Christina Knight’s story, accompanied by the sounds of Navajo Nation, in a special audio version of this report.

“Underserved” is a polite way to describe Navajo Nation, which stretches 27,000 square miles through Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. At least a third of its 400,000 citizens, almost half of whom live on the reservation, suffer from diabetes, heart conditions and lung disease. Poverty and addiction are prevalent. Medical funding and resources are scarce.

“As indigenous people, we’re always at the bottom,” says Wanda Begody, a Navajo woman who lives in Coal Mine Canyon, Arizona. “We don’t have enough doctors.”

Knight ’13, ’17 MD came to Chinle to help address this need, although she couldn’t fully grasp the range of hardships faced by the Navajo people until she witnessed them.

A well of strength got her through that first night, and then she went straight to working 12-hour shifts at the Chinle Comprehensive Health Care Facility.

She had completed her residency at Indiana University just a month earlier and had no introduction to the Navajo culture or community, which the year before had logged the highest rate of COVID-19 infections per capita in the United States. She felt incompetent, her inner voice nearly justifying an urge to quit with a mantra of “I’m doing more harm than good being here.”

But then, at the first week’s end, she was assigned to care for an elderly Navajo patient.

The old man’s mind was sharp, but a bout with COVID had severely scarred his lungs. Knight explained to his daughter that treatments couldn’t help, her father wasn’t going to survive. Making him comfortable should be the priority. The daughter agreed and requested that his extended family, about 20 people, be with him in his hospital room.

They feared the pandemic meant he’d die alone.

“That’s not going to happen,” Knight promised.

She arranged for her patient to have his own room, and family members, all vaccinated and masked, gathered by his bedside.

“After he died,” Knight says, “his daughter came out and said to me, ‘Thank you. You gave us something we didn’t think we’d be able to have.’”

Knight returned to her apartment that night and cried. The omnipresent wind blew.

“His death almost broke me,” she says, “but then it ended up saving me as well. I realized that I could advocate for people.

“I thought, if I can advocate for somebody — get something for them that they were afraid they otherwise wouldn’t get or make that person’s life better or give them something that they will value — then I will stay here, stick it out and do that.”

Gallup, New Mexico

Flags snap in the wind, and the aroma of fry bread, roast mutton and leather wafts through a flea market on the outskirts of this town. Hundreds of booths line four rows on a gravel and dirt patch between train tracks and U.S. Route 491. Knight is browsing along with thousands of visitors who traveled from throughout Navajo Nation.

“This is a great opportunity for me to see and learn more about the culture,” she says.

Knight credits her time at Ohio State for teaching her the importance of understanding cultural context. Her education abroad experiences included a summer in Guatemala — her first visit to her home country since Canton couple Susan Parker Knight ’81 and James Knight adopted her at 4 months.

In the Central American country, she noticed that patients responded well if she spoke Spanish, their native language, and if she listened carefully to them. She learned that getting to know people helps her provide better care for them.

“You need to have cultural humility,” Knight says. “You have to be able to step back and say, ‘I don’t know your traditions or cultures or native medical practices.’ Otherwise, you jump to conclusions.”

In Navajo Nation, Knight has learned always to address the oldest family member first. With poverty and unemployment rates both at about 40%, she has come to ask two questions of every patient: Do you have electricity? Do you have running water?

“Most of them don’t have either,” she says. “You have to take that into account when you’re making decisions about a lot of treatments. People in our society say, ‘If you’re going to be healthy, you have to do this, this and this.’ It’s not practical in Navajo Nation.

“A big thing that I’ve learned is that you’re not here to be like, ‘I know better than you; we’re going to do it this way.’ It takes so much collaboration to yield a successful result.”

Getting results also is challenged by a lack of resources. There are few medical specialists and surgeons for the reservation’s 12 health care facilities, which together accommodate 200 hospital beds. That is one bed per 900 residents, about one-third the overall U.S. rate.

“Where you live impacts your health care, and this is a stark reminder,” Knight says.

She thinks of that when driving along the plains, mesas and mountain passes of Navajo Nation — larger by area than 10 U.S. states — with an occasional home sitting off in the distance like a lone raft lost on a brown ocean.

Phoenix is 300 miles from Chinle. Flagstaff, Arizona, is 170 miles away. It’s 230 miles to Albuquerque, New Mexico.

“You have expectations in your mind of how rural it’s going to be, and then you get here and it’s, ‘Oh, wow,’” Knight says. “I was shocked by how remote it is.”

She has since learned about a child who died from a heart ailment because an ambulance took an hour to get to her family’s home. One of Knight’s first patients was a construction worker who walked more than 40 miles every day because he didn’t have a vehicle to get to work.

Sometimes her patients don’t show up for scheduled appointments. Knight understands.

On this blue-sky Saturday, she traveled 90 miles from Chinle — the occasional wind gust shaking her car — to visit the market outside Gallup.

Here, she mingles as merchants sell traditional silver and turquoise jewelry, hand-woven rugs and blankets, western wear, tools, birds and rabbits, NFL merchandise. Pop songs mix with indigenous music.

“You just see this is the way of life for people,” she says. “The markets help maintain a lot of connections to family, friends and traditions.”

Strolling among thousands of market-goers, she encounters one of her patients, herb seller Yeii Yazzie. They hug. His friend’s grandson — a 2-year-old in a cowboy hat and boots — stands next to Knight, who is wearing an Ohio State fleece.

The little boy reaches up and grabs her index finger. He doesn’t let go.

Chinle, Arizona

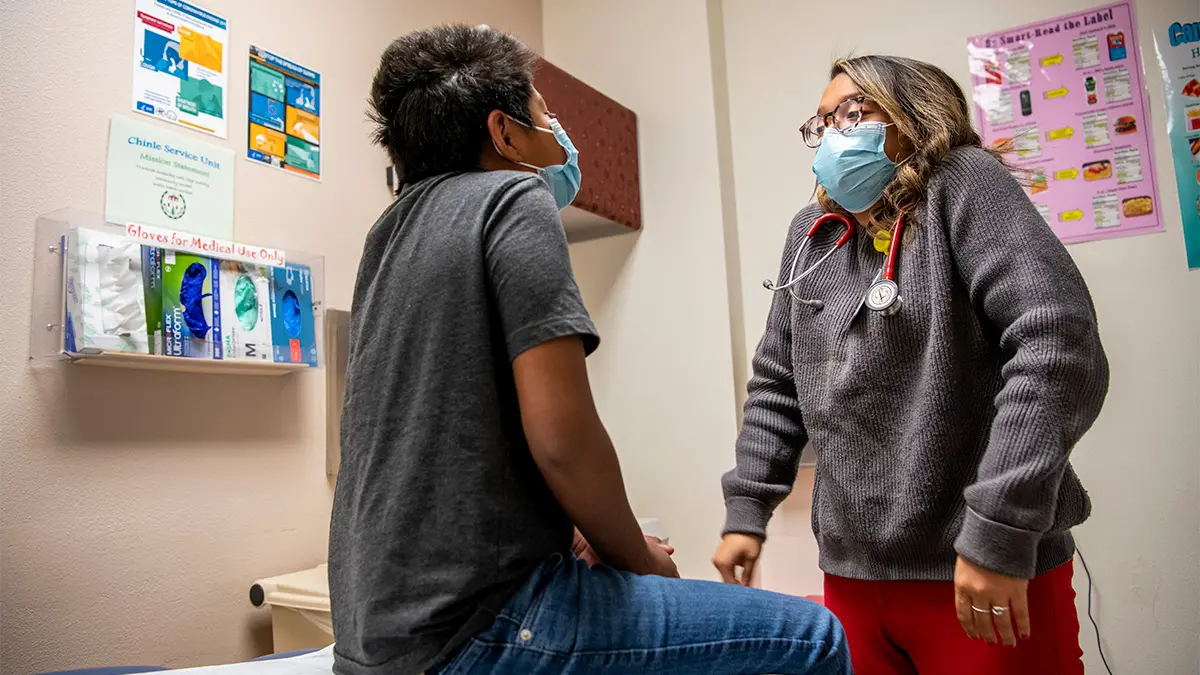

Deep inside the maze of the Chinle Comprehensive Health Care Facility sits a patient explaining to Knight how numbness in his legs and mobility problems have worsened in the two years since he was stabbed near the spine.

“When I walk, I kind of stagger around,” he says. “People think I’m drunk, but it’s my balance. My legs stiffen up.”

Knight intently observes the man, who appears to be in his 20s. She’s a sponge for details.

The two talk for 30 minutes. After examining him, and to make certain she’s clear about one point, Knight draws a spinal cord on a piece of paper. The patient leans toward her whenever she speaks.

After presenting her treatment plan, Knight asks: “Anything else you’re worried about?”

On this day during her 8 a.m.-to-5 p.m. shift at the hospital’s internal medicine clinic, she sees four adults and six children, and she asks this of everyone.

“Sometimes it takes one question to learn more about them,” Knight says. “In medicine, you can start to tunnel your diagnosis or solution because you assume so much. When you do that, you shove everyone into one group.

“I feel like, if I assume anything, then I failed my patient. You have to keep a curious mind — that’s what I always tell myself.”

Navajo patients have told Knight enough about their lives and circumstances in the past year that she has come to a realization: They’re concerned about being stereotyped.

“I tell them that if there’s something wrong, I need to know,” she says. “But they fear they’ll be confirming society’s beliefs that they get everything for free and don’t have to do very much or work very hard.”

Knight saw the results of that fear play out months earlier while examining a young man who had fallen off a truck while unloading hay. She noticed his ankle was bruised and swollen. “Oh, I’m walking on it. It’s fine,” he told her.

Knight kept asking questions and finally convinced him to get an X-ray. The results showed he had fractured and displaced both his fibula and tibia. Knight gasped.

“The way she practices medicine is being informed by the patients she’s seeing there,” says Dr. Jane Goleman ’79, ’82 MD, who mentored Knight at Ohio State while teaching in the College of Medicine. “She’s in touch with people who have very little, and knowing how to interact with them as a physician is so important.”

Quiet by nature, Knight enrolled at Ohio State to become a biochemist. However, she began volunteering at Wexner Medical Center during her freshman year. She’d bring flowers, talk to patients and family members. The enjoyable interactions convinced her to become a doctor — the type of physician appreciated in Navajo Nation.

“For our people, it is very important to have a health care provider treat them like a human and truly listen to them,” says Chinle resident Shaun Martin.

Knight’s soft skills helped Yazzie, the man she’d later see at the Gallup market, after he had traveled 80 miles from his home on the Black Mesa in Arizona for a two-day hospital stay in Chinle in November 2021.

“She treated me for dehydration,” Yazzie says. “I thought I was taking care of myself, but overall, I wasn’t. Once I talked to her, I understood. She communicated different things about dehydration that I never thought were an issue.”

Four months later, Knight cradles a baby as the mother looks on at the Chinle hospital. The infant whimpers, and the doctor softly pats his head. “Oh now, it’s OK, kiddo,” she says. The baby calms as the examination ends.

“He’s doing great, Mom,” Knight says. “You and Dad are doing a fantastic job.”

There’s a pause, and then, just in case, she asks another question: “Is there anything else you’re worried about?”

Outside Chinle

The view is spectacular from the lip of Canyon de Chelly National Monument, where a March wind cuts hard and cold along sandstone walls. Knight peers out from a south-rim perch 1,000 feet above the canyon floor.

“You feel a connection to where you are,” she says. “You’re in a very special place to these people. Their profound history is here.”

Canyon de Chelly, on the eastern outskirts of Chinle, has been occupied by indigenous people for nearly 5,000 years. Small farms are still tilled below its red cliffs, among the cottonwoods.

The land’s dichotomy — beautiful yet harsh — is further evident a couple of miles away, where a grandmother cooks dinner for nine in a Chinle trailer that has a wood-burning heater, no running water, tires on the roof.

“Some people probably look at us like we’re poor, but we’re not,” says Vergie Yazzie, no relation to Knight’s patient. “We love our life and the way we live. We have each other, and we have our land. We have our lifestyle, and it can be hard.”

People like Knight who come into Navajo Nation to help don’t have the benefit of growing up with the local customs or having family around to lean on.

“That’s a huge commitment for her to give up a year of her life and come to Chinle. Most people want the easier path,” Martin says. “It’s a unique person in the world today who seeks out hardship.”

Knight still struggles with the isolation, which she sometimes compares to solitary confinement. A counselor helps her maintain her mental health. So, too, do reading, listening to podcasts and watching movies on DVD. She goes on hikes and, occasionally at night, exercises by walking in circles inside her apartment — sometimes covering up to 6 miles in two hours.

She is glad she didn’t quit, proud of her resilience when loneliness swirled for her here in Navajo Nation, where community well-being is valued over individual needs. “I do love doing this,” she says.

After a day’s hospital shift ends, she isn’t alone. Knight sits with seven co-workers — each here on health care stints from throughout the United States — around a dining room table in the home of nurse practitioner May Tanay.

They meet once each week for a potluck dinner, an outing they call “Wednesday Night Fellowship.” The gatherings have bonded the former strangers. “We sympathize with each other and help each other,” Knight says.

Filipino cuisine is shared amid a circle of nonstop conversation. They discuss how not all of the reservation’s feral dogs are dangerous, how “Dan the Postman” at Chinle’s only post office is so friendly, how tickets have gone on sale to see singer Harry Styles in Phoenix — a five-hour drive away …

“What is this guy’s name?” Tim Frey, a radiologist from Boston, asks about Styles. Incredulous, his dinner mates explode in laughter.

For two hours, eddies of topics swirl around the table: tattoos, favorite TV shows and comfort food, mnemonic devices, mosh pits.

Knight is swept up in communal laughter. Their joy is so loud you can’t hear the wind.

Knight has made it a point to understand and respect the Navajo’s connections to their history and home. Here, she has paused while hiking the Hope Arch trail, west of Chinle.

Here, There, Everywhere

Sometimes at night, when the Chinle weather cools and the wind calms, Knight stares at a sky bursting with brilliant stars.

The Navajo have their own constellations, created so their people could gain understanding about the passage of time, growth and aging. Their stories share principles and values for living.

Knight also finds purpose in gazing at the nighttime kaleidoscope of light.

She thinks about how those same stars create a connection with her birth mother in Guatemala — a single mom and maid whom she never knew — and her adoptive parents in Ohio.

She thinks of choices they made — and ones awaiting her in the future.

“My life started with nothing,” Knight says, tearing up. “I had negative value in the country where I was born: I was female, of indigenous heritage, born during the end of a civil war.

“And here I am now because my mom was like, ‘No, this isn’t the life that I want for my child.’ She completely changed my life with just one decision. Same with my parents who raised me.

“I can do that for somebody else. I can change something with just one decision. We all can.”