Q&A with illustrator Adrian Franks

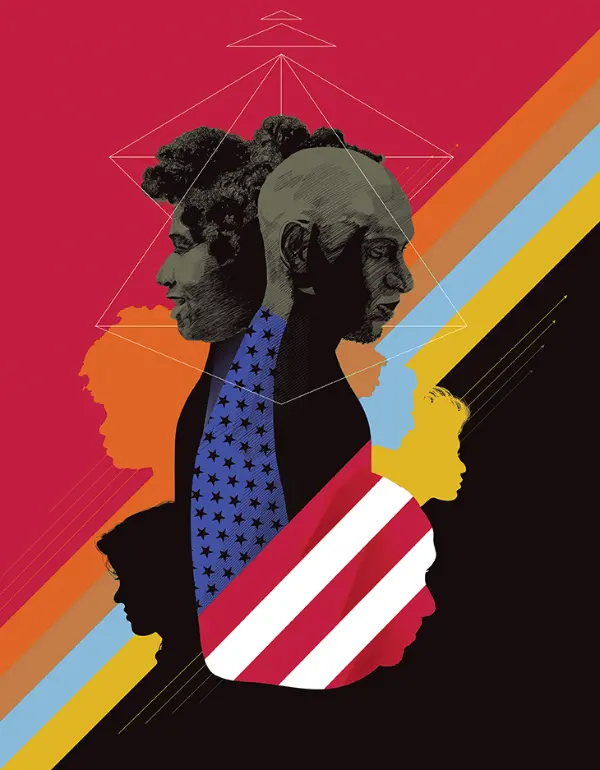

Franks, who created the art for the magazine’s feature on racial justice, talks about bridging the worlds of marketing and art, creating in order to spark conversations and the story behind his Janus-inspired illustration.

Courtesy of Adrian Franks

Adrian Franks

-

You have your full-time job, which is working in UX/UI and marketing. How did you transition from the work at agencies in your day job to freelance illustration and fine art?

It’s weird because, I know they’re different, but they’re kind of the same — it still involves designing and solving problems for humans. Some of the work has come from people I’ve known in the past from former jobs, and some is from things I post on social media accounts.

-

Some of your work from the Suspicious Prisms series has been printed out and used as posters during recent social justice protests.

They are kind of like graphic obituaries of people who have been killed by police brutality. That’s a series I typically don’t like doing. But I feel compelled that I have to use my talents to convey a moment and help people understand that these are humans who are no longer here. That can kind of get lost. It’s terrible to constantly have to add to that series, and the sad thing is, what about the people I don’t know about? I’ve tried to quit the series many times before, but … Yeah.

-

When did you start the series?

It started with Sean Bell, who was killed the day before his wedding [in 2006]. Undercover cops in New York City unloaded like 40-some rounds of ammunition into his car as he and some guys were leaving a club. And the details are kind of blurry. And then Jonathan Ferrell, who was a football player at Florida A&M University, was shot nine times after being in a car wreck. Those two guys inspired the series and, unfortunately, it’s continued as time went on.

-

You also have another long-running series, Fearless, that seems to affirm the contributions and accomplishments of people of color.

That’s a silhouette series that celebrates people who deserved it, from Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. to even just personal friends. Even people like Steve Jobs, because he was a visionary. He was a fearless individual. I wanted it to be very broad in terms of personalities and multicultural. And I wanted to highlight the way that these different individuals took on different aspects of society.

-

It almost seems like those two series balance each other.

I didn’t think of that perspective of juxtaposition at the time, but yeah, both of those series started during the Obama administration. They reflect my thinking at the time. And now, I haven’t done a Fearless piece in quite some time, not during this current administration. One should definitely be fearless during this era. But it feels like there’s a lot of fear being put out.

-

You are having more trouble finding positivity right now?

Yeah, I’m just trying to figure out what should I talk about. Right? Because one would say you should talk about positive things and create possibilities in a time like this. But sometimes it’s easier said than done. Creativity is an emotion. And to spark that emotion you need some motivation. And I just haven’t been motivated to think about the future. That could change, of course. I’m hopeful that something positive will come from the current situation that we’re in as a country now.

-

Given how busy you are, I was really surprised that you agreed to taking on this assignment for the magazine so readily. What appealed to you about the assignment?

I saw the ideal of what you guys were trying to do — that Ohio State has a history with marginalized groups of people. And it seems like you are trying to actually acknowledge that and reconcile and find solutions. That was what appealed to me. It’s one thing to say, I only want to do work for The New York Times or The Washington Post, but something like the Ohio State Alumni Magazine can reach communities and audiences that these big publications can’t truly reach. And more focused audiences and communities can have deeper conversations. The solutions to these problems are going to be found locally. That’s why I like to also get involved in grassroots efforts as well.

-

What was the thinking and inspiration behind your illustration?

I wanted to make sure that I incorporated people. At the center of this tapestry of people, I wanted to address what was going on — that African Americans have been dealing with racial injustice since we got to this country. But I didn’t want it to just represent a specific man or woman, so I made this Janus-like figure. And if you notice, the man’s not smiling, but the woman has more positivity to represent different outlooks. And the tapestry of people surrounding them represents that this affects all Americans. Racism doesn’t just affect the people directly dealing with it.

It’s very much like the pandemic, right? Not all of us are sick. But all of us are affected. And it won’t get better until the sick are well again. You are only as healthy or strong as the core group of people who are sick.

And it’s like that with systemic racism as well. Whether we are talking about police brutality or red-lining or whatever, at some point it’s going to affect everybody. That’s the point of the illustration: what happens to this marginalized group of people affects the whole country. To get through this, we have to do it together and solve the problems of all of our citizens.