President Kristina M. Johnson: A light in the storm

She joined us as a most extraordinary academic year began, undaunted by the challenges and inspired by the Buckeyes she now leads.

Some 20 years ago, Kemi Doll and a few other Duke undergrads were eating pizza during their National Society of Black Engineers chapter meeting when the dean dropped by unannounced.

Today, Doll is a gynecologic oncologist, researcher and assistant professor in Seattle. Her former dean is Kristina M. Johnson, 16th president of The Ohio State University. It’s been years since the two last conversed, but each credits the other for imparting precious knowledge.

“What struck me most is that she would come to our events. I remember the first time just being like, ‘You’re the dean. Why are you here?’ Her response was something like, ‘Because I want to know what your experience is. You all have an experience nobody else has at this school. You have incredibly valuable information for me.’”

Between that first meeting and her graduation in 2004, Doll faced hardships that forced her attention away from her studies. She recalls Johnson coming to her dorm room to help her make a plan to quickly get home to Atlanta and then later, when poor grades forced Doll to sit out two terms, the dean gave her a job while she prepared to reapply to the biomedical engineering program.

Johnson and her wife, Veronica Meinhard, speak with former President Michael V. Drake on the day of Johnson’s appointment. Logan Wallace

“It was a very empowering position for me, as I continued to move through medical school and residency and all these places where being ‘the only’ again was very normal, to realize, ‘Wow, I have this incredible value to bring.’ She was the first person who articulated that to me.’”

Examples like this — of Johnson’s lasting effect on others, through small gestures and huge achievements — come to mind easily for former students, longtime colleagues and cherished friends. Listening intently and speaking authentically in every conversation. Earning the prestigious John Fritz Medal and a spot in the National Inventors Hall of Fame for her expertise in optoelectronic processing systems and 3D imaging. Seeking out the daughter of a search committee member to share appreciation for her new Buckeye mask. Securing more than 100 U.S. and international patents. Stooping to pick up a piece of litter and carrying it to the next trash can.

This is who Kris Johnson is. How she moves through life and brings others along.

And what a life it’s been. Johnson, 63, officially joined Ohio State on Sept. 1, but was deeply engaged with the university community in the weeks leading up to this extraordinary academic year. She was born in St. Louis and grew up in Denver before heading to California for her bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees in electrical engineering from Stanford and then to Ireland for a postdoctoral fellowship at Trinity College.

When it came time to join a faculty, she accepted an offer from the University of Colorado at Boulder. In her 14 years there, she founded a National Science Foundation-supported center in optoelectronics and spun out several companies, including one that brought new 3D technology to market for films such as “Avatar.”

Next she served eight years as dean of engineering at Duke and two as provost and senior vice president at Johns Hopkins before President Obama tapped her for the role of undersecretary of energy. She accepted and was unanimously confirmed by the Senate.

Following that government service, Johnson founded (and with technology innovations quickly grew) a company to generate sustainable hydropower, an industry her grandfather and father helped pioneer. In 2017, the lure of academia led her to the role of chancellor of the 64-campus State University of New York system. And on June 3, 2020, The Ohio State University Board of Trustees named her to succeed former President Michael V. Drake.

“Ohio State has always been a special place to me, well beyond its standing as one of the most respected teaching, research and patient-care institutions in the world,” says Johnson, whose paternal grandfather was a Buckeye. “This is an iconic, inspiring, storied institution. Our size, scale, scope — with 15 outstanding colleges, a respected graduate school and top institutes and medical center — enables limitless potential to do great things.”

But Johnson isn’t naïve. She knows the road ahead is fraught with unavoidable adversity: a pandemic to overcome, structural racism to continue tearing down, concerns about college access and affordability. These are only a few. Yet she’s not dissuaded; she’s motivated.

“I think different times require different types of leadership,” Johnson says. “Calm, agile, optimistic, collaborative, empathetic — these are traits I feel I draw my strength from. And an always-present sense of urgency. If you want to be the best and have a world-class research and educational operation, you have to have a sense of urgency. You have to get things done.

“I’m also pretty competitive, but in a good way. And being competitive, putting in the work, having a winning spirit — I think that matches really well with The Ohio State University and Buckeye Nation. I mean, we want to win. That’s who we are.”

Johnson stresses she is all about teamwork — and former associates back that up with numerous examples.

“I want to hear from everyone, and I want to make sure that we look at issues from all the important aspects so that when we make a decision, we appreciate and understand the impact. What excites me about Ohio State is our ability to do innovative things because of our capacity and our influence. When we do something, we’ll make an impact.”

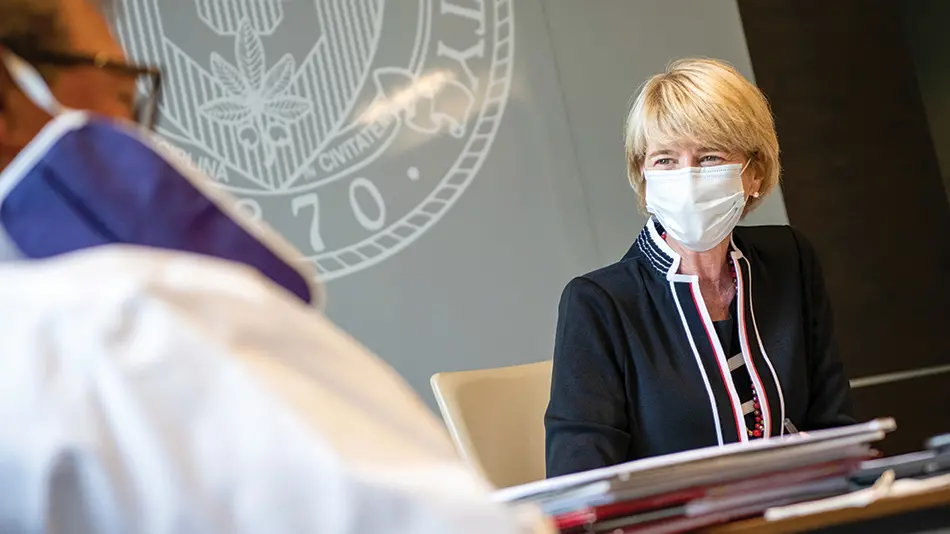

The president leads a session with her cabinet of senior leaders during her first day on the job. Her initial meeting with the Board of Trustees came later in the week.

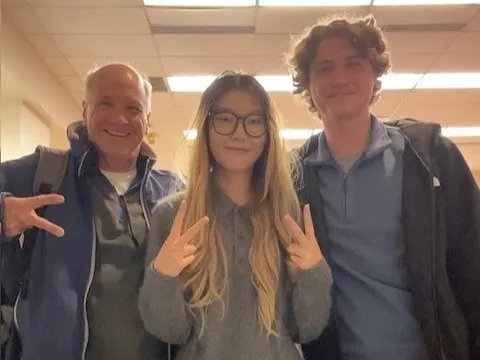

Johnson bumps elbows with a parent during move-in. Normally a one-day feat, the process was extended to 12 days to limit campus visitors because of COVID-19.

‘Connecting the dots’

Bob Freelen easily recalls Johnson’s lasting first impression. He and his wife, Sally, were residence hall fellows at Stanford, and Johnson was a freshman whose room was next door to their apartment.

“She knocked on our door and said, ‘Do you have a drill?’ I looked at her and said, ‘Not really.’ What she did when she eventually found a drill was hook her bed to a pulley arrangement so she could fold it up against the wall during the day. She thought the twin bed frame took up a little more room than it needed to, so she rigged it up.”

The Freelens were Johnson’s dorm mentors for just two years, but their friendship has spanned 45.

When Johnson’s mom visited that first year, the Freelens honored her request to stay silent about the used motorcycle she’d purchased to tool around town. They followed her athletic career — she played varsity field hockey and founded Stanford’s lacrosse club, among other achievements — and applauded her academic successes. When she defended her PhD dissertation after surgery to remove her spleen and months of radiation to treat Hodgkin’s lymphoma, they were there. (On overcoming lymphoma, Johnson says, “It taught me a lot. About optimism, courage, being strong and how to face unpleasant events and deal with them. It’s not a club I wanted to be part of, but I’m glad that I am.”)

For Bob Freelen, who went on to roles as Stanford’s dean of students, alumni director and vice president of public affairs, watching Johnson’s career unfold has been pure joy. “The combination of outstanding academics and entrepreneurship is really quite rare. You just don’t see very many people who can combine those two things and really be extraordinarily successful at both.”

That ability to lead a complex academic enterprise and navigate the worlds of industry, government and technology — and to do so while putting people first — elevated Johnson to the top of what Ohio State Trustee Lewis Von Thaer believes was a field of “the best candidates in the country” for the president’s job.

“We definitely wanted to find a hybrid candidate, somebody who had succeeded in academia but also had had to succeed in the business world or government or somewhere like that,” says Von Thaer, who chaired the presidential search committee that worked closely with an advisory group of students, faculty, staff, alumni and community members. “We wanted somebody who, at their core, was an academic and could understand the academy, work in that shared-governance structure, but also could push to get things done and drive schedules in weeks and months instead of semesters and years.”

Von Thaer understands the importance of that pace better than most. For three years he has been CEO of Battelle, the world’s largest independent research and development organization. Its headquarters is right across King Avenue from the Columbus campus.

“I think if there’s bureaucracy that gets in the way too often, Kristina will find ways to move that out. When the scientists work together, stuff usually goes pretty well; smart people like working with smart people,” he says. “An ability to focus on academic excellence, to partner beyond the university and do bigger things — she brings exactly that skillset. And there are a lot of smart Buckeyes around here.”

Johnson has the same impression about ingenuity within the Ohio State community. She recognizes the grand challenges already being met by colleges, institutes and centers across the university and expresses eagerness to more deeply explore existing and potential interdisciplinary links.

“We have all the pieces. What I’ve done in my career is connect the dots on the various pieces through cross-disciplinary and what now we refer to as convergent research,” she says. “What I mean by connecting the dots is getting together and identifying really important problems that society needs to solve. And then putting together the networks on campus and in the greater world to converge with a singular focus and make an impact on a particular problem.”

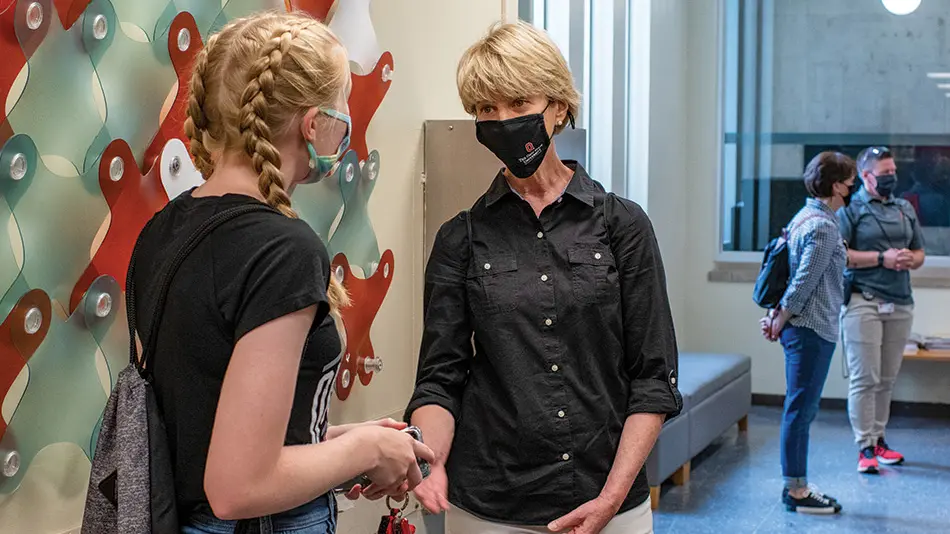

A desire to interact more with students such as freshman Emily Smith is a big reason Johnson chose to move from the role of SUNY chancellor to Ohio State president.

During an interview before taking office, Johnson conveys the energy she finds in this moment. “I’m an engineer. I love solving problems. I view them as opportunities, challenges — and I’m inspired by challenges.”

‘Her interest in people is in all people’

Ram Narayanswamy has seen that laser focus up close. He worked with Johnson as a grad student at the University of Colorado beginning in 1991 and through a two-year postdoctoral fellowship.

“I still remember when I met her. It was brief; her calendar is very busy. I mean, she’s always going somewhere, right? It was probably a 20-minute meeting, but that really left a mark on me. I thought, ‘Wow, she is really visionary. She has all this energy.’ I don’t remember what we talked about, but I said, ‘Hey, I want to work for her.’”

Narayanswamy was undecided on his focus when he joined Johnson’s research group. They explored options and talked with colleagues, and on her recommendation, he chose to develop what we now know as artificial intelligence to improve the effectiveness of Pap test cancer screenings. He developed the means to isolate data that fell outside the normal range so doctors and technicians could bring their experience and judgment to bear in the most crucial cases.

“Academics can be very focused on doing what they do. Kristina is able to connect it to a bigger horizon and say, ‘Listen, there’s some greater good in this. There’s some technology here that we can use to solve big problems.’ She’s an amazing bridge builder that way, understanding some of these issues and how technology can solve them.”

One solution badly needed throughout public higher education is the creation of more opportunities for students and faculty from diverse backgrounds. Johnson admires the gains made during Drake’s presidency and vows diversity, equity and inclusion will remain a priority during her tenure.

“We need to push it. At the end of my term here, I would like to see a significant change in our demographics,” she says. “It’s keeping your eye on the recruitment processes and procedures, bringing people into the system so they can be seen and be productive and get the opportunities that everybody else has.”

Robert Clark was a professor and researcher at Duke when Johnson persuaded him to take on an associate dean role. Now provost at the University of Rochester, he and Johnson brought greater racial and gender diversity to Duke’s engineering faculty by creating new faculty lines and holding search committees accountable for widening their candidate pools.

Clark says fostering opportunities for others is at the heart of who Johnson is and how she views her responsibility as a leader. “Kris is a very warm person, a very caring person. And so her interest in people is in all people. It doesn’t matter what your race is or what your culture might be or what your gender identification is.”

All of this came through to Von Thaer and others charged with finding the next person to lead Ohio State’s six campuses, more than 68,000 students, about 7,600 faculty, some 28,000 staff members, nearly 600,000 alumni and a $7 billion annual budget.

“Kristina’s very courageous, and she’s not afraid of a challenge. She is passionate about this job and becoming a Buckeye,” he says. “It’s never easy to step into the crisis when you come in on your first day, but leaders do that. They’re not the ones who run away from the fire. They run into it and try to solve things for their organizations, to make it better. She’s showing that spirit.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated Nov. 16, 2020, to accurately reflect the size of Ohio State’s faculty.

Johnson and Ken Lee, a professor of food science and technology, zip between meetings. Despite the pace, she’s listening intently, a trait mentee Dr. Kemi Doll saw decades ago: “She has her ear to everyone in this very genuine way. It just creates such confidence in what she can do.”

Johnson generations: driven by family values

Kristina M. Johnson didn’t know her paternal grandfather, Charles Johnson. He died in the 1917–19 flu pandemic when Johnson’s dad, Robert, was just 5. Johnson lost her own father when she was a sophomore in college. While these loved ones from three generations spent too few years together, they shared important commitments — to education, sustainability and, now, the Buckeyes.

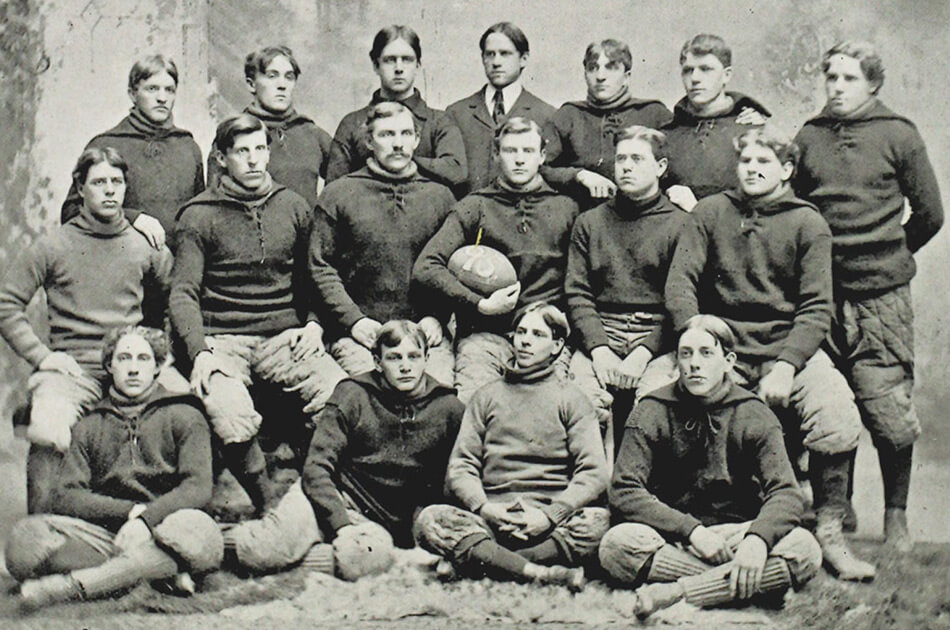

Charles Johnson, an 1896 graduate of Ohio State, studied engineering and played right guard on the football team. Family lore suggests her grandparents met on campus. While working for George Westinghouse in the early 1900s, Charles Johnson launched Casino Technical Night School, named for the restaurant where classes met.

“He recognized that women and African Americans were not the engineers of the world,” Johnson says. “So he started night classes to educate anyone who wanted to get into the technical tracks within Westinghouse.”

Among Johnson’s prized possessions is a 1920 letter Black employees of Westinghouse sent her grandmother, Evelyn Vaughan Johnson, recognizing her late husband’s “great service … to Negroes in the community of Pittsburgh.”

Johnson’s dad worked for Westinghouse, too, and like his father, in hydropower. When her term as undersecretary of energy ended, Johnson saw her own path to the field. She founded Enduring Hydro, which evolved to Cube Hydro with support from a private equity firm, and brought in Neal Simmons, one of her former Duke postdoctoral fellows, as vice president for engineering and innovation. They built the first new hydroelectric facility in western Pennsylvania in 25 years and modernized 18 existing plants in five states.

“Working with Kristina is a tremendous amount of fun,” says Simmons, a Duke professor who is CEO of the company Johnson stepped away from to lead SUNY. “We did a lot of important things in a very short time. She really just drove her vision throughout the company to innovate and bring technology to hydropower where it hadn’t been.”

Johnson attributes her commitment to sustainability to being one of seven kids raised by parents who grew up in the Depression. “My mother’s favorite saying was, ‘Waste not, want not.’ There are only so many resources in the world and to waste them is just not right.”