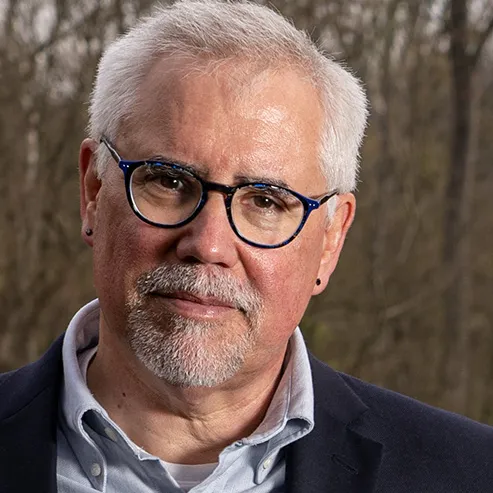

Bill Mitsch brought wetlands know-how to the people

The distinguished professor established the Olentangy River Wetland Research Park and was a leading researcher and academic.

A chance encounter with Chicago’s first Earth Day event inspired an epic career shift for Bill Mitsch, launching a lifetime of research, teaching and advocacy on behalf of marshes, bogs and swamps. His pioneering work helped shape the disciplines of wetland science and ecological engineering, and he left a legacy for future students in a watery corner of Ohio State’s campus.

William Joseph Mitsch, retired School of Environment and Natural Resources Distinguished Professor and founder and first director of the university’s Wilma H. Schiermeier Olentangy River Wetland Research Park (ORW), was 77 when he died Feb. 12, 2025, in Columbus. His death was mourned and his life celebrated by his family, colleagues from around the globe, and his many students, including the former graduate advisees he fondly called his “wetlanders.”

Most of Mitsch’s research, which included more than two decades at Ohio State, focused on how effective wetlands are at improving water quality, says Jay Martin, a professor of ecological engineering in the Department of Food, Agricultural and Biological Engineering. In 1992, Mitsch created the research park on the banks of the Olentangy River to serve as a hands-on classroom and living laboratory for long-term research while also promoting the value of wetlands to society. “With his work at ORW and across the globe, he demonstrated that you can design, restore, create wetlands that will reduce nutrient levels [such as phosphorous, which can feed algae blooms] and reduce other types of pollution,” Martin says.

In other words, as Mitsch was fond of saying, “wetlands are the kidneys of the world.” And always a teacher and advocate, he created kidney-shaped basins for his first two experimental marshes, to drive the point home. Those were followed by an oxbow wetland, a bottomland hardwood forest and controlled outdoor environments for experimentation.

“And he was far-sighted enough to make it a park, not just a research facility,” Martin says of the facility, which connects to the Olentangy Trail and includes benches and walkways through the wetlands. “He was responsible for a lot more than just building knowledge of wetlands within science. He was building knowledge about the science of wetlands with everybody. And that was huge.”

The sixth edition of his book, Wetlands, published in 2023, is still the definitive textbook for wetland ecologists everywhere. In 2004, Mitsch was awarded the prestigious Stockholm Water Prize for his research, outreach and advocacy, and his models and techniques are now widely used around the world for sustainable water resources management.

He was founder of Ecological Engineering, the top journal of the discipline, and edited the publication for more than two decades. He was a founding member of the American Ecological Engineering Society and in 2018 received the organization’s first Odum Award for Ecological Engineering Excellence. A former president of the Society of Wetland Scientists, Mitsch received the SWS Lifetime Achievement Award in 2007.

Mitsch was born in Wheeling, West Virginia, and learned his love of nature in the creeks of the Ohio River Valley, says his wife of 55 years, Ruthmarie, who once taught French at Ohio State. Mitsch became a mechanical engineer “because he loved math, and his father was an engineer,” she says. After graduating from the University of Notre Dame, he went to work for Commonwealth Edison in Chicago, but didn’t find his true vocation until age 23. That’s when he went out for lunch on April 22, 1970, the nation’s first Earth Day, and listened to speakers raising the alarm over increasing environmental threats to the land, air and water.

“When he came home all hyped up about Earth Day, I’d never seen him quite so turned on about something,” she says. “I was happy to see him really embrace something.”

That enthusiasm persisted throughout his career and infected his students, recalls Siobhan Fennessy ’86, ’88 MS, ’91 PhD, a professor of biology and environmental studies at Kenyon College and one of Mitsch’s first graduate students at Ohio State. “He was in the office every day unless he was traveling,” says Fennessy, a “wetlander” from 1986 to 1991. “His door was open, and you could walk in his office any minute of the day, and he would never mind. He loved it, actually.”