Called to serve

Sister M. Xavier Schulze ’11 discovered life was more than basketball while at Ohio State. Today, she lives with total commitment — faith, love and joy in full measure.

She’s clutching uprooted basil in gloved hands, beads of sweat dotting her forehead below a black veil. Her full-length gray habit billows in the prairie breeze, years after she heard a religious calling that became embraced vocation and delivered her on this day to a Nebraska field.

Working nearby is Judy Obert, 76, caretaker of this community garden for Hastings Village, a senior housing neighborhood where she lives. Hoe in hand, she pauses to query the visiting Roman Catholic sister, who at 6-foot-1 stands tall among surrounding fruit and vegetables.

“Sister, you went to Ohio State?”

“Yes.”

“Did you play sports there?” Obert asks.

“I played basketball,” Sister answers.

She mentions nothing else. Not a word about her Buckeye teams going 106-30 and winning three Big Ten titles in 2007–11. Nor that she was a starter her final two seasons, leading Ohio State to the NCAA Tournament’s Sweet 16 as a senior co-captain.

She was known as Sarah Schulze then. Now she’s Sister M. Xavier Schulze, the name she chose in August 2013 as a novice in the Sisters of St. Francis of the Martyr St. George. She entered the order in Alton, Illinois, a mere 18 months after her final Buckeye game.

Sister is too humble to give details to Obert about her playing days, but she’s not running from them. She owns Ohio State pajamas and got so excited watching the Buckeyes win the 2024 football national title that she would jump up from the couch and yell at her convent’s communal TV. She wears black and gray, but she bleeds scarlet and gray. “Ohio State is where I fell in love with Jesus,” she says.

She defined herself by sports as a youth in Anna, Ohio, but a change in self-identity at college began a decade of discernment, religious training and preparation, that led to Aug. 2, 2022. That day, she made final vows and became a perpetually professed Catholic sister, pledging her life to chastity, poverty, obedience and serving the church. Now 36, Sister is a teacher and director of campus ministry at St. Cecilia Catholic Middle & High School in the rural town of Hastings, population 25,000.

“I’m living the good life,” Sister says. “I feel very settled, peaceful, fulfilled. There’s not any part of me that’s like, ‘What if?’ I’m very happy in my vocation, in my apostolate. I’m just happy. I feel like I’m living my dream job.”

The work has her kneeling in garden dirt on an October afternoon, toiling alongside five St. Cecilia students as part of their school’s homecoming week service day. They’ve come from weeding and cleaning a neighbor’s home. In the morning, Sister and 40 students packed meals for global distribution at a Hearts & Hands Against Hunger event.

Sister leads a group of high schoolers in a day of community service.

Before working in the garden, the group cleaned up the home of an elderly community member.

“Sister is showing them they’re part of a community and that everybody gives a little to the community no matter your age,” Obert says. “And then service becomes part of you.”

The five quiet teenage boys remove spent vegetation to help put the garden to bed before season’s change. Sister guides them, pointing out ripe cherry tomatoes to save. “Arnold, there’s a big juicy one right in the middle,” she says. “See it? It’s to the left. Right there.”

A train’s rumble is heard from the distance, a common sound in Hastings. Founded in 1872, the town has another era’s vibe. Residents are polite to strangers, even known to leave extra fruit and vegetables on porches and in unlocked cars as gifts. They live in an isolated place, 160 miles from big-city Omaha, but aren’t removed from the world’s distractions and challenges.

Sister spends daily life helping her students navigate all that noise, but to get here, she first had to make personal changes as Sarah.

Class began with quiet prayer and writing, but late-morning silence in St. Cecilia room M202 is broken by the crackling energy of students scrambling to compete in an activity designed by their teacher.

This seventh-grade theology class has been discussing types of books found in the Bible—historical, major prophets, gospels. Sister wrote those names on colored slips of paper, dumped them on the floor and split her students into small teams to see what they’ve learned.

“Put the books in logical order,” she says.

“Can we use our notes?” asks one of the 18 students.

“No, use your brain,” replies Sister, who wanders the room, kneeling to better hear groups sprawled on the carpet.

Everyone is excited but calm, reflecting the peace that permeates this pristine school, a two-story building showing little of its 69 years due to a recent remodeling. Sister has taught at St. Cecilia, five blocks from downtown’s main street, since 2020. She knows every name of the 223 students, grades six through 12.

Nearly all the enrollment hails from Hastings, a commercial agricultural town totaling 10 square miles of modest homes with well-trimmed lawns. In 1927, chemist Edwin Perkins invented Kool-Aid here, which is celebrated with an annual festival. Folks parade through downtown’s billiard table-flat streets that are litter free and lined by well-kept buildings, many from the late 1800s.

“Hastings is kind of the same as where I grew up in Anna,” Sister says. “They’re salt-of-the-earth people here, more focused on human things than material things.”

Sister struggled to broaden her own focus as a teenager, the middle of three children raised Catholic on her parents’ 28-acre Shelby County farm with steer, goats and sheep. “I was so self-centered,” she says. “Everything was about me, specifically everything about me in sports. That was my life.”

Besides excelling in basketball at Anna High School, Sarah won individual state titles in track (800-meter run) and cross country before a major knee injury in her sophomore hoops season spurred personal change. Forced away from sports, she turned to living with a stronger faith commitment to find order and meaning in her life.

The search continued at Ohio State. As a freshman in 2007, Sarah began going to daily Mass, set aside a holy hour of personal reflection each day, and led pregame prayers at teammates’ request. Still, a lack of playing time often left her crying in frustration until a year later when she read the book Come Be My Light. That collection of writings by Mother Teresa of Kolkata inspired her to become a missionary sister instead of pursuing previous plans for pro basketball, marriage and children.

“Change is about allowing life to form you for the better,” says Sister, who majored in comparative religious studies in the College of Arts and Sciences. “Life is like a training ground. You have to be aware that God is using everything in your life to inform you. If you’re aware of that, change is not scary.”

Although she never mentioned becoming a sister, Sarah’s religious devotion impressed Ohio State coaches, staff and teammates. They saw her take leftovers from team meals to feed the homeless. Saw her go to Mass every day for four years. Saw how she lived.

“We all respected Sarah and her faith,” says guard Brittany Johnson ’11. “She never pushed it on anybody. We knew her faith was so important to her, and we were all for it.

“I was her roommate on the road sometimes. Whatever city we were in, she’d always find a Catholic church. She’d say to me, ‘I hope I don’t wake you tomorrow, but I’ve got to get up at 6 a.m. to go to Mass.’ I was like, ‘That’s fine. You go, girl.’”

Sister and her parents, Jill and Mark Schulze, say they appreciate how all members of the Ohio State program respected and supported her needs to practice faith. They particularly praise head coach Jim Foster, who made scheduling allowances for her, even once cutting short the team’s morning workout before a road game so she could make it to Mass on time.

“It was really easy because Sarah was so committed to everything,” Foster says. “She was a great student and teammate who practiced and played hard. She was very strong in her religion, and whatever responsibilities that came with those beliefs, she felt obligated to carry things out to their maximum. As a coach, you own that and do whatever you can to help that along.”

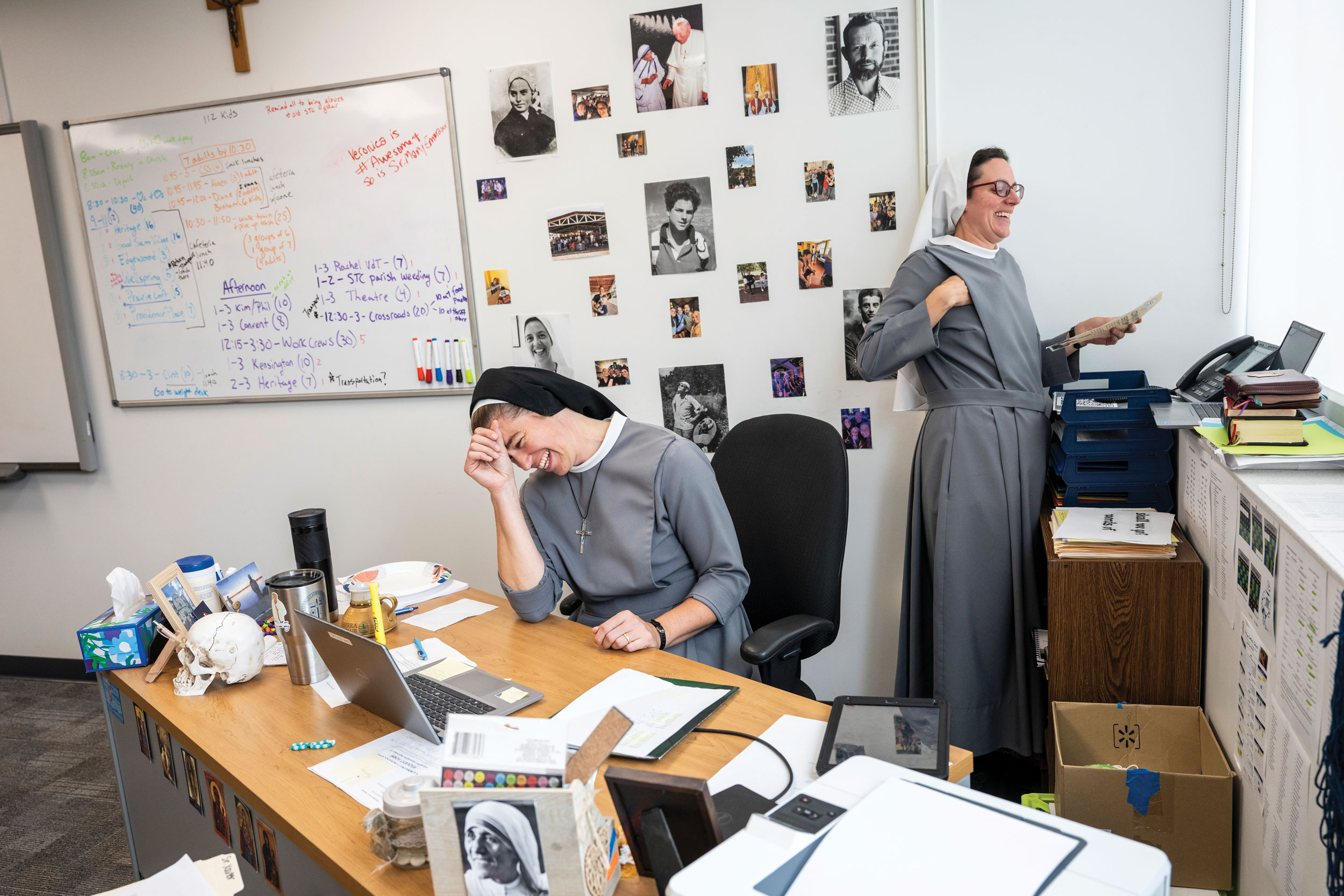

Sister brings that same passionate commitment to St. Cecilia, where she lives on school grounds with two other sisters in a small brick convent built in 1952. “She’s kind of an all-in type of person,” says Sister M. Margaret Gibbons, superior of their convent. “She has a lot of energy, zeal and enthusiasm for everything she does. It’s fun to see.”

Convent life is austere, regimented and communal. The sisters share cooking and cleaning duties. They’re prohibited from wearing makeup or earrings. Personal cellphones or computers aren’t allowed, but Sister can use a school computer for work. On weekdays, she awakes in her own small bedroom at 4:45 a.m.; on weekends, she sleeps in until 5 or 5:30 a.m. Morning Mass precedes school hours, followed by late afternoon prayers and Scripture reading. Dinner in the convent, then recreation for 45 minutes. Night prayer. Silence from 8:30 p.m. until morning.

With Sister at this prayer service are sisters she lives with and ones from her order in Alton, Illinois. The younger visitors are working through the stages that lead to final vows, which she has completed.

“We have what we need to live our daily lives and live out our apostolate,” Sister says. “I love helping people encounter Jesus, and that’s the majority of what I get to do by meeting with kids.”

She meets them with empathy in theology class when some students snicker about a classmate struggling to correctly write a word on the whiteboard. “Hey, you guys, give him a break,” Sister says. “It’s nerve-racking to spell in front of a whole class. I experience that every day.”

After class, she walks with students to the gym basement, where the cafeteria is a hive of unleashed chatter and giggles—a buzzing contrast to Sister’s mandatory annual one-week silent retreat.

She stands in lunch line with students, who say things that make her tilt her head back in laughter, mouth wide open. Sister grabs a tray and accepts the same meal they’re served: hot dog, baked beans, string cheese.

“You have to see yourself in them,” she says, “and they have to see themselves in you.”

Sister runs the school chess club and takes her games, and the students, seriously.

As part of her ministry, Sister discusses how to have hard conversations with a student club. Veronica Clark—in pajamas for spirit week—reads tips Sister developed.

Throughout the St. Cecilia campus, students orbit around Sister or trail in her wake when she walks. They come and go freely from her school office, sometimes for serious talks, but often simply to hang out, joke around, chill.

“She’s a fun, bubbly person,” says senior Veronica Clark. “People like being around her because she truly cares for them, and she’s not going to judge them no matter what. She loves everybody. She’s obviously not an actual mother but has a motherliness.”

Clark and nine classmates are comfortable with Sister during an upperclassmen leadership group meeting. They lounge on the office’s two sofas and slouch on stools, yet all listen intently as she offers tips about how to confront and better communicate with someone who has upset them. “Maybe start by thinking that the other person is worth the risk of the conversation,” Sister says. “Deciding to do that is actually a huge act of love.”

Most of Sister’s work time is spent as director of campus ministry, often in student group meetings like this or individual counsel sessions. She also holds weekly chess club meetings and plans activities, school events and community service projects to nurture students’ religious and personal growth.

“Students are always looking for some kind of leader,” says Father Cyrus Rowan, chief administrative officer at St. Cecilia. “They’re looking for some fulfillment, somebody to give them something that is going to help them grow, give them some meaning. Sister provides a lot of that just by her very presence in this school.”

Sister says “spiritual motherhood” with students is humbling and her favorite part of her vocation. She also just enjoys being around the students, especially middle schoolers because they’re unformed, inquisitive, quirky and silly. “I’m goofy, so I like being goofy with the kids and having fun,” she says. “You don’t have to be serious all the time. People have movie conceptions of stiff-neck nuns who hit you with a ruler. It’s not quite the same in real life.”

When it’s time to be serious with students, Sister draws on her own emotional struggles during her athletic life. She was a self-described terrible loser. After one high school defeat, she punched out a locker room window.

“I always had this interior frustration and anger,” Sister says. “I let my emotions rule me. This is something in general that our culture struggles with. Slowly but surely, I learned through the grace of God how to be guided by reason, not emotion. But it was something I struggled with a lot until I got injured at Ohio State.”

As a senior, she blew out her knee against Michigan State on Jan. 16, 2011. Her career seemed over in devastating fashion. “Lord, what are you doing?” she asked silently at next morning’s Mass. An answer came in that moment. “I understood in my heart,” she recalls, “that God was saying, ‘You’ve always said that I’m more important. Now can you live that?’ I was like, ‘All right, let’s go!’”

Realizing a full religious identity, Sarah departed church that day feeling freed from stressing about the pressure of competing in sports. With medical clearance a month later, she strapped on a bulky knee brace and played the last seven games.

“It was such a gift to finish my senior year,” Sister says. “That’s when I started playing for Jesus. I had lost my starting spot and couldn’t do what I normally could do as a player. It was hard, but I knew it really wasn’t the end-all and that I was so much more than basketball.

“I went through the ringer with mental health issues before, went to counseling twice. I’ve come to a place of stability and wholeness. I see how the Lord has used all my struggles to now allow me to help the kids. The suffering I went through has made me more credible and relatable to them.”

Fourteen years later, Sister sits in her inviting office with 10 high schoolers, each fully engaged as she advises how to break bad emotional habits and best approach a difficult talk with others. “If you’re being vulnerable, then the other person is more likely to be vulnerable,” Sister tells them. “That’s not easy because you want to win the conversation, but you have to know that it’s not about winning the conversation. It’s actually about seeking communion.”

Later, in a quiet post-meeting moment, one of the students reflects on her five-plus years of guidance from Sister. “She’s authentic,” Clark says. “She really knows how to talk to people with straight facts. Some people just tell you what you want to hear. She corrects me when I’m wrong because she wants what’s best for me. She has showed me what it’s like to be a humble, good person. Sister has changed my entire life.”

There’s a small basketball hoop in Sister’s office and a garbage can shaped like a rim and net in her classroom. It’s no secret at St. Cecilia that she played for Ohio State. “My reputation follows me,” she says. “Sometimes it’s my sisters who spill the beans. They think it’s really cool.”

Sister has a gym key and occasionally goes there alone to shoot, but she’s surrounded by family on this fall Sunday. Her parents drove 15 hours from Anna with three grandchildren for a visit that mom says feels like Christmas Day. Sami Kremer, her younger sister, her husband, Ben, and their two sons also came from Ohio.

Nieces and nephews, ages 1 to 11, frolic as Sister entertains by juggling plastic bowling pins and doing the Hula-Hoop. Soon, she’s sweating in a one-on-one basketball game against Ben, dribbling behind her back in full black habit, veil and sandals. “She oozes and radiates joy all the time,” Sami says.

Sister last saw her family in June on a home trip, which her vows allow once every two years for 10 days. She can email but only talk with them by phone once every six weeks for 30 minutes. Weekend visitors are permitted twice a year. “It wasn’t just a change for her, but for the whole family,” Jill says. “It’s an adjustment, and that process takes a while. At first it was hard for us, but it’s much easier now, all good. I always know she’s safe.”

Jill and husband Mark weren’t surprised in December 2011 when their daughter told them her intention to become a sister. She says her family has been “rock stars with their support” the past 14 years, even on the most challenging day for everyone, in September 2012 when the family dropped her off at the convent in Alton, Illinois.

Sarah walked in wearing an Ohio State shirt and shorts. She walked out to say goodbye in a Catholic jumper, a postulant in the first stage of formation.

“At that moment,” Jill says, “it became very real to me that my daughter just gave up all her earthly belongings to follow our Lord. I still get emotional talking about that day, but my tears are not sad tears; they’re proud tears.”

Sister’s faith, sacrifice and dedication so amaze her father, Mark says he sometimes stops to pinch himself. “There are no do-overs,” he says. “You get one shot on this Earth. She really stepped forward.”

Steps in the 10-year process to final vows took Sister to Franciscan University in Steubenville, Ohio, for her Master of Arts in Theology degree, to Cuba for a two-year mission, and to Hastings, which might not be her forever post. She goes where the church sees need. At the path’s start in 2012, a former Ohio State teammate received an envelope postmarked from Sister M. Xavier.

“I was like, who is this?” Johnson says. “I opened it, and there was a handwritten letter. I started reading and thought, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s Sarah.’ She told me about being postulant and the process she was going through. I was ecstatic. I’m super happy and very excited for her now and what she has become. She’s a phenomenal person who puts others before herself. It’s hard to find that type of person in this world now.”

You find Sister on a fall dawn in Hastings, walking the St. Cecilia halls with guitar in hand, a customary morning sight. She’s strumming chords as groggy students arrive for school’s start.

“Come to chapel,” Sister says. She strolls and plays as lockers open and bang shut. “Nora, you coming to chapel?”

She says yes and follows the guitar sound.

“Praise the Lord,” Sister says. “Emily, you coming? Sarah? Come on, Leon.”

The boy nods, agreeing to go with her down the hall to the “Praise and Worship” service before first 8 a.m. class. “Good decision,” Sister says and smiles.

About 25 students and three visiting postulant sisters join her inside Our Lady’s Chapel on the school’s first floor. They pray, sing hymns along to her guitar playing, then all kneel.

Sister stares ahead at the altar.

It’s so quiet, you can hear a nearby train, and maybe something else.