Unveiling of riches

Through the Carmen Collection project, a wealth of powerful stories from throughout Ohio State’s first century and a half is being discovered and amplified. They will live in perpetuity in University Archives. Without them, our history would not reflect our reality.

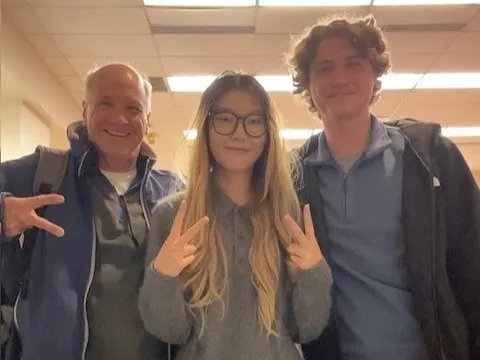

Ginette Rhodes ’19 (left) and University Archivist Tamar Chute utilize the vast resources of University Archives in their Carmen Collection research. (Photo by Jo McCulty)

Ginette Rhodes ’19 took her audience back in time.

Leveraging archival material such as looping documentaries, photo albums heaped on tables and a giant timeline of historic events, Rhodes guided fellow Buckeyes on an unexplored journey of Ohio State’s story. She told of little-known researchers, entrepreneurs, drum majors, professors, doctors, linguists and more.

She started at a logical beginning: her own.

Projecting a picture of herself as a baby in 1997 on a large screen, Rhodes explained how her grandmother Nola was the first person to hold her. It was the birth of a close bond, one that would build through the years based on many shared passions, including a love for research.

“She’s very proud of the truth,” Rhodes said of her grandmother, who spent years researching the history of slavery in the United States.

On this evening, Rhodes was speaking to members of Women & Philanthropy at Ohio State, a group of alumni and friends who support students and faculty. Her topic: the Carmen Collection, a collaborative project to unearth seldom-told stories about members of the university community and put them on display during Ohio State’s sesquicentennial year.

“When I accepted my position as a research intern for the Carmen Collection, I immediately called [my grandmother],” she recalled. “We talked about the power of being a voice when voices are lost along the way.”

“It’s important for people to see these stories and say, ‘I can do what they did. I can be a voice for change.’”

Voices have, indeed, faded during the first century and a half of Ohio State’s existence. That reality led University Archivist Tamar Chute to propose the idea for the Carmen Collection a little over two years ago.

“We know the big decisions, the big events, the presidents. But there are so many more stories that have made up the university,” Chute said. “Not telling their stories is not telling the legitimate history of the university.”

In mid-2018, Rhodes and fellow Carmen Collection researcher Reyna Esquivel-King ’19 PhD meticulously combed through a mountain of historic resources: Lantern articles and Makio yearbooks that stretch back to the 1880s, oral histories, 110 years of alumni magazines, biographical and subject files — quite literally, whatever they could get their hands on.

Along the way, they dug up stories of determination, optimism, compassion and success involving people of all backgrounds and walks of life, illustrating the diversity of personalities who built Ohio State.

It didn’t take long for Rhodes to dust off a gem.

Opening avenues of accessibility

Tucked away in a lost cranny of university history was the story of Jean Williams, whose tale was eclipsed by that of Julie Cochran. Both women helped bring down accessibility barriers for students with disabilities. But while Cochran’s plight received coverage in newspaper and yearbook articles, Williams’ story was virtually unknown until Rhodes began sifting through University Archives’ subject files.

“Finding that story was so significant,” Rhodes said. “It shows the value of what the Carmen Collection is, that we can share stories of determination that made an impact on education for everyone here.”

As of the early 1970s, 33 buildings on the Columbus campus were inaccessible to students with disabilities, and only the first floors of an additional 11 could be reached. Because Williams ’68, ’70 MA and Cochran ’70, ’74 MA used wheelchairs, friends and faculty discouraged both from attending Ohio State.

Neither listened.

Williams enrolled in 1962 and was one of few African American women at Ohio State at the time. The majority of her classes were in University Hall, which was not wheelchair accessible. So, her brother carried her up the steps to class every day.

Cochran arrived in 1966 and was told she could not attend classes required for her major because they were on the third floor of Derby Hall. Upon learning this, 35 members of Delta Chi fraternity took turns escorting her and carrying her up the steps to class each day.

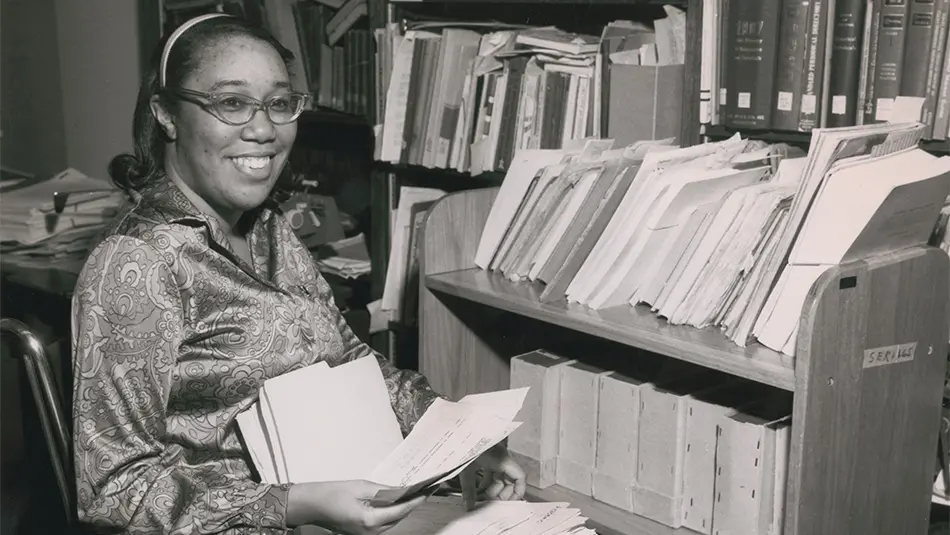

Jean Williams works in Thompson Library. When she enrolled in 1962, barriers to accessibility led her brother to carry her up the steps to her classes. (Photos from University Archives)

Julie Cochran faced similar challenges when she arrived four years after Williams. Members of the Delta Chi fraternity helped her navigate to class.

Cochran’s first trip down a ramp outside Hagerty Hall gave her a chance to show a sense of humor that matched her determination and resilience.

Williams, second from right, went on to serve on the Columbus advocacy group Courage Inc., which recognized Ohio State for its early gains in accessibility.

Cochran’s story garnered more attention in The Lantern and from other students because it came at a time when the issue of accessibility was a national topic.

In fact, 1972 graduates used their class gift to dismantle many accessibility barriers. The class invited Cochran to speak at campus events and raised $75,000, which helped the university qualify for federal dollars.

That funding resulted in transportation services and housing accommodations for those with disabilities, modified buildings and street curbs, a library for people with visual impairments and establishment of the Office for Disability Services.

The university was recognized for these efforts in 1973 by Courage Inc., a Columbus advocacy group that Williams chaired. The timing of these advancements was significant: Ohio State’s accessibility efforts began almost two decades before the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.

“If you go into any building on campus today, there’s this idea that of course there are elevators and ramps,” Chute said. “That’s not the way it always was — and the effort was started by students. It shows the power of research and what we can share with people about determination and why it makes an impact on education for everyone here.”

Uncovering untold stories

The tenacity Cochran and Williams demonstrated is threaded through many Ohio State stories. Another involves Pomerene Hall, built in 1922 and dedicated specifically for women’s use. Maybe you knew that. But did you know Caroline Breyfogle, the university’s first dean of women, and others pushed for 10 years for a gathering place for female students?

It’s possible you knew Ohio State has always been co-ed. But why? “It’s because the agriculture professor, Norton Townshend, for whom Townshend Hall is named, sent his two daughters to register for class the first day the university opened,” Chute said. Often, it’s not just the facts that are important, she added, “it’s the why.”

And the reality is, many people swam upstream to find a place for themselves at Ohio State — and to make a place for those who followed. The value of their example cannot be overstated.

“It’s extremely important for future students to see their history and know they’re not alone, that these groups have been here — and they struggled — but they overcame,” said Esquivel-King, who researched the history of Latinx groups on campus along with that of LGBTQ and Asian groups. “Not all the stories are positive; there’s still work that needs to be done. These stories bring issues to light.

Rhodes conducts research for Carmen Collection stories at University Archives. (Photo by Logan Wallace)

“Students can work together on these problems,” she added. “Yes, it’s for the 150th anniversary celebration of Ohio State, which is great, but it’s also a way to look at what has been done, what can be done and what we can do to improve the environment at Ohio State.”

Rhodes — whose research focused on women, African Americans, students with disabilities and veterans, among others — said her exploration led her to realize many of the stories were strikingly similar to current issues she sees discussed on social media.

For instance, the Women’s Grassroots Network of the early 1990s has much in common with today’s #MeToo movement. Current discussions in the African American community echo concerns about civil rights in the 1960s.

“It’s important for people to see these stories and say, ‘I can do what they did. I can be a voice for change,’” Rhodes said.

Chute also hopes the project will be a launching point for more stories to be researched, uncovered and brought forth. “The stories are extremely powerful,” she said. “The most important outcome of the project is to retain these parts of university history in the archives so that when Ohio State celebrates its 200th anniversary, this history is part of what we already know.”

Inspiration from the Carmen Collection

(University Archives)

Newark’s Earthworks have long been considered a wonder of the ancient world. Built by people of the Hopewell culture more than 2,000 years ago, they are the largest set of geometric earthen enclosures in the world. And when a country club wanted to expand its golf course, eating up more of the earthworks’ land, Christine Ballengee Morris drew a line in the sand.

A Native American of Cherokee-Appalachian descent, Ballengee Morris is an Ohio State professor in the Arts Administration, Education and Policy Department and former American Indian Studies coordinator. She organized a group, Friends of the Mounds, to protect the land.

The group helped establish Newark’s Earthworks as a National Historic Landmark and as Ohio’s official prehistoric monument. Acting on a Friends of the Mounds proposal in 2006, Ohio State’s Board of Trustees established the Newark Earthworks Center on the university’s Newark campus.

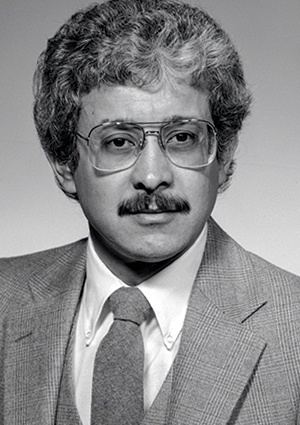

(University Archives)

Alpha Psi Lambda is the first and largest co-ed Latino fraternity in the nation, with 33 chapters in 16 states and more than 3,000 members. But it didn’t exist until 1984, when Ohio State’s Josué Cruz began leading the effort to form it. The Latino organization became official in February 1985, and 13 male and female students at Ohio State were initiated on March 10 of that year.

It’s one example of Cruz’s far-reaching legacy for the Latinx community at Ohio State. Hired as Ohio State’s assistant vice provost for the Office of Minority Affairs in 1983, Cruz helped establish numerous groups, including the Hispanic Graduate and Professional Student Organization, before moving on in 1996.

He also assisted several academic departments in minority recruitment and retention efforts. One of those was the Research Apprenticeship Program, in which underrepresented high school students from Franklin County served as interns in the medical, veterinary sciences, biological sciences and pharmacy disciplines.