Terry Esper’s a pro at untangling the supply chain

The Fisher College professor explains how prices, shortages, war and COVID-19 all play into the knotty web of U.S. logistics.

COVID-19 shined a light on unexpected areas of life. For one: shopping.

From the lack of merchandise on shelves to the rise in home delivery, we suddenly cared deeply about supply chains and how products get to our stores and doorsteps.

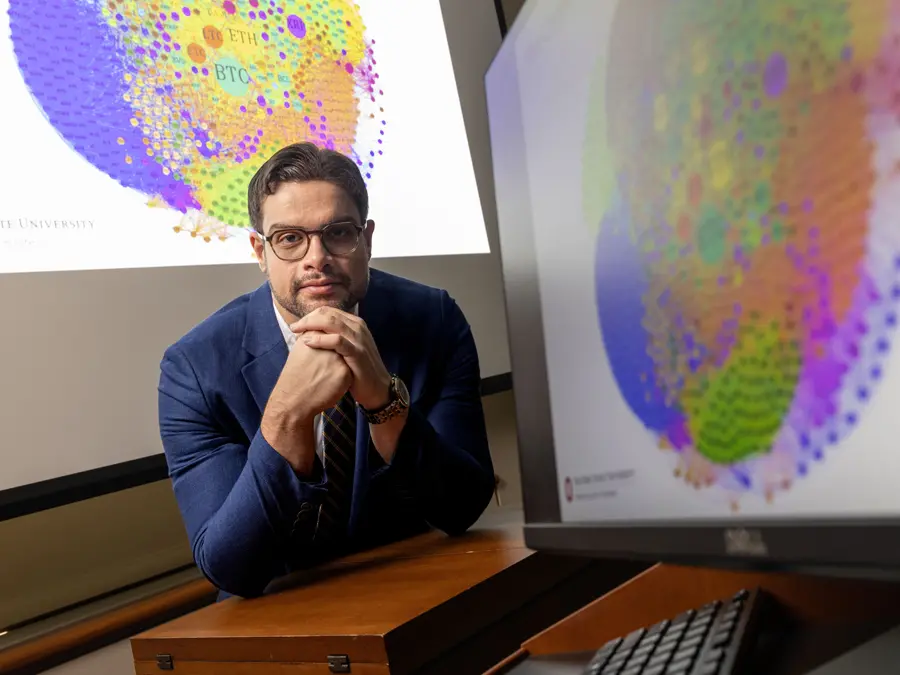

Terry Esper has cared about this for three decades. The Fisher College of Business professor examines how companies rely on supply chain and logistics operations. He investigates everything from getting products to market to better online shopping experiences for businesses, customers and delivery workers.

Here, he breaks it down for the rest of us.

-

Currently, what are the most critical items affected by shortages? — Barbara Petroff ’67, ’94 MS

Shortages became a really big topic with the onset of COVID, and we’re still seeing areas of critical shortages, not so much around COVID anymore but other issues. For example, the war in Ukraine.

Ukraine and Russia, particularly Ukraine, are responsible for a lot of grain and corn production. That affects products like bread, corn, vegetable oil. Some analysts are suggesting that before 2023 is out, we will see shortages in those areas and also beer, bourbon and even Champagne. During COVID, there was a big uptick in demand for Champagne, somewhere in the area of a 70% increase.

There are also big shortages in the pharmaceutical space. The ADHD medication Adderall, particularly the generic, is experiencing problems getting to market. The same with Ozempic, a medication for diabetes, because production can’t keep up with the demand.

The big recent story was Girl Scout Cookies. Production couldn’t keep up with unpredicted demand and it became a fiasco.

-

What do you believe are the main causes of shortages in the supply chain? Also, is this going to be the norm moving forward? — Christopher Thoman ’90

We’re looking at 2024 before we get back to some degree of normalcy. Again, COVID and the war in Ukraine are the big reasons why. COVID especially changed a lot of our consumption, which caused more demand for some products and less for others. But those areas where it stimulated demand, that’s new demand and demand not adequately forecasted.

There are also issues with labor. Even in situations where demand was adequately predicted, some companies are saying they just don’t have the manpower to manage the throughput to fulfill the demand.

And there’s also the global trade conversation we’re dealing with now. Many companies have moved around the globe, in terms of where they’re manufacturing products. We’re seeing a lot of shifts in how businesses are managing their supply chains.

-

What is the latest timeline for computer chip manufacturing to begin producing large quantities of product in the U.S.? — David Roberts ’73

I would say 2024–25 is when we’ll see sizeable shifts in U.S. computer chip manufacturing.

This is an important topic for us in Central Ohio, getting the Intel facility. It’s projected to start production in 2025. There’s one ahead of that in Arizona, expected to start production in 2024, and another in New York, even larger than Intel, which should begin production in 2026–27.

Auto manufacturers have been so debilitated by the lack of chips, they’ve actually started to decrease the number of options they’re making available in some vehicles just to be able to get product out.

-

Will egg prices come down this summer? — Timothy Dunleavy ’77

According to the USDA, egg prices will drop. They have dropped over the last couple of months, and they’re suggesting a 30% decrease. Of course, this was all associated with an avian flu that caused a significant reduction in hens, which caused egg production to go down. But now they’re forecasting prices will drop.

-

What solutions have been developed since the COVID pandemic to alleviate shortages of essential goods like medicine and food? — Robert Jones ’73

According to a recent survey, almost 80% of supply chain executives said technology investments had increased significantly as a result of COVID. So, investments in things like artificial intelligence and robotics.

A lot of supply chains are being debilitated by the labor crisis, but those same companies are saying, “Let’s invest in robotic technology so we don’t have as much need for human talent.” AI is starting to be infused to allow for more precise predictions than maybe what a human can provide.

One other important change is what’s called “friendshoring.” You have offshoring, which is when a company puts manufacturing in China or Indonesia. Friendshoring is where companies take into consideration the geopolitical landscape, locating facilities, doing manufacturing and distribution in countries that do not have a volatile relationship with the U.S. Some companies started looking for these solutions even before COVID because of the trade war discussions with the Trump administration in 2019. Companies are moving operations to other areas of Asia, such as Singapore and Malaysia. It’s become a matter of national security.

-

I understand many of the shortages were due to lack of fuel for trucks, lack of drivers. Is there any way to prepare for such things in the future? — Karen Scott ’84, ’86 MS, ’89 PhD

Fuel prices go up and down, but driver turnover has been a big issue for a long time. That was one inspiring thing to me about the onset of the pandemic, people thanking truck drivers, people recognizing them as essential workers. They became like heroes because they were on the front line, putting their lives at risk to get products to shelves. If there was any indication about how powerful drivers are, remember last year what happened at the Canadian border, when truck drivers shut down automotive manufacturing.

Delivery workers have become very significant now. They’ve become a big solution for companies — the crowdsourced or gig worker, DoorDash, Uber Eats. Those drivers are making a world of difference.

We’re also starting to see the Uberization of transportation, where if I’m a truck driver, instead of me driving for a major corporation, I can just drive for whomever needs me to drive. That’s starting to provide another avenue of driver talent for companies needing to move freight.

-

[When you invited alumni to submit questions, you described Esper as studying] racial bias for drivers. Do you mean they are being hired on a diversity basis rather than on a merit/experience basis? — Lt. Col. Ross Simon ’60

First, let’s talk about truck drivers. There has been a concerted effort to ensure diversity in those spaces. The driver labor pool is shrinking and one of the solutions has been to tap into spaces that haven’t been previously tapped to find truck driver labor.

One of the most widely growing communities in the truck driver space is women. There’s a whole initiative around diversifying from a gender perspective, and it opens up many opportunities for more driver labor and talent.

But with that comes some interesting issues. I’ve been having a lot of conversations with corporations about their diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives because a lot of those initiatives don’t cascade to the warehouse, to the distribution center, the truck dispatchers. Those are work environments that can still be considered hostile to some. So that’s one layer of the diversity conversation. I’ve worked with corporations to be more intentional about making sure these DEI conversations include implicit bias discussions and finding ways to work together.

The second layer came because we had begun to see so many more people getting into home delivery because of COVID. DoorDash, Uber Eats, Amazon Flex — those areas have become a major supplemental side hustle for people.

But whereas truck drivers are driving big trucks, when someone is driving a Honda Civic through your neighborhood, it can get charged when it comes to issues of race and bias. I started looking at this in 2020 as we were having so many heated racial discussions in this country, and we did see a significant increase in the number of incidents of drivers being accosted, harassed.

I focused in particular on African American male drivers because that’s where the issue was most pronounced. But there was also a significant number of Asian drivers being harassed as they were finding their way to addresses to deliver products.

It wasn’t just, like, DoorDash drivers in unmarked cars. It was people driving large FedEx trucks. One of the most egregious situations, still in litigation: A FedEx driver was shot at when he was trying to deliver a package. So I’ve worked with FedEx and UPS and other corporations to find solutions to these problems.