How one Ohio State study can change lives

New research validates an alumna-created system that helps adults with intellectual disabilities get physically fit and avoid chronic health problems.

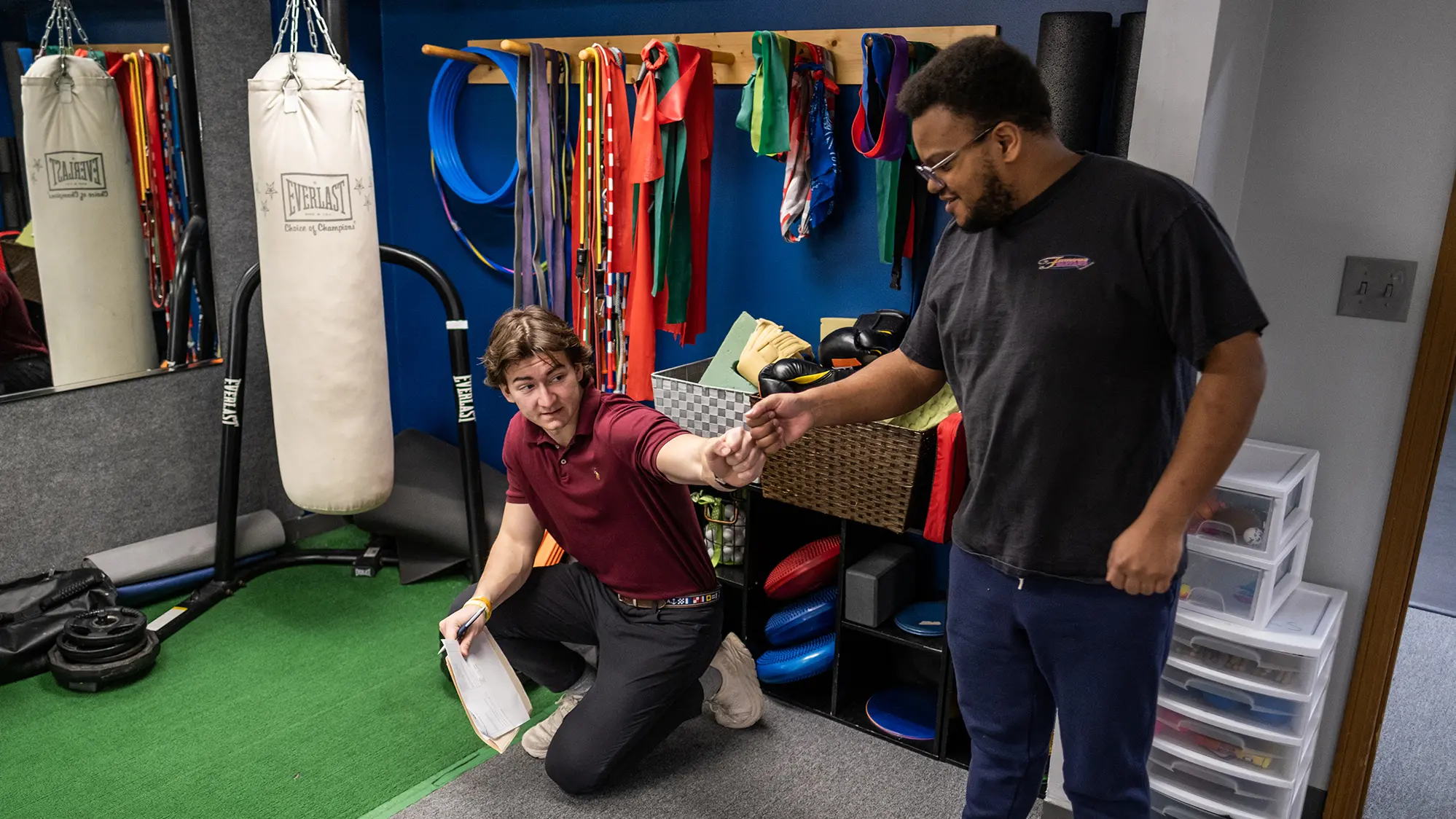

Ohio State student Anthony Dujmovic ’22 guides Kristen Manifold at Valemee Fitness in Dublin, Ohio, before testing her bench press strength for the study he helped guide and run.

His name is Zayne Harshaw and right now he wants everyone to know, “This is my jam, right here.”

He is sitting up on a bench press, the opening riff from “Crazy Train” by Ozzy Osbourne crying out from the phone in his pocket. Zayne promptly lies back, grips the bar as instructed, and proceeds to push out six reps of 140 pounds, straight to the sky.

The 27-year-old sits up, breathes out and asks, “Did I break the record?”

Ohio State’s Carmen Swain ’97 MA, ’07 PhD and Anthony Dujmovic ’22, who are spotting him in the lifting area at Valemee Fitness gym in Dublin, Ohio, laugh and answer. He sure did.

Zayne rolls up his sleeve, flexes his arm. “I’m getting a tattoo of a flaming guitar pick on my muscles. I’ll need a shirt to show it off.”

The guitar pick recognizes his passion: jamming in his band Blue Spectrum. The new and improved muscles? The result of an eight-week Ohio State study.

Zayne has autism. He was one of 25 participants in the VALID Study, designed and carried out by Swain ’97 MA, ’07 PhD, senior lecturer of exercise science, and Dujmovic, an undergrad when the project started and now a PhD student in physical therapy.

Video: Anthony Dujmovic & the VALID study

In this video, Anthony Dujmovic ’22 shares how the study he undertook to help adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities turned out to be a life-changing experience for him. Runtime is less than 2 minutes. (Video by Daniel Combs)

The study explored the effectiveness of an exercise system designed to promote fitness, independence and self-efficacy for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD). The system was developed by Peggy Mills ’80, MA ’93, owner of Valemee Fitness, where the study took place from October 2022 to February 2023.

Mills retired early from her role teaching adapted physical education in the Dublin school district to start Valemee in 2017. Her reason? She saw many of her former students experiencing health issues related to a lack of fitness once they became adults.

“When you look at lifelong fitness, there isn’t much out there for this population,” Mills says. “There are gyms on every corner, but you can’t walk into one and say, ‘I’ve got a person with autism, train them.’ It’s not going to work if you don’t know the language, how to de-escalate them, motivate them, adapt exercises.

“Our system is visual, it’s simple and keeps them on a predictable routine. I just know it works.”

Swain and Dujmovic now have the data to back that up. Swain says the study results — 96% participation and excitement to continue exercising — were like nothing she had seen before. Not only that, participants and their parents loved being involved.

“The feedback was so powerful,” Swain says. “And there was so much hugging. That’s what I remember. People came in, wary of you, and left feeling so confident, so empowered. Of all the research I’ve ever done, this was the most meaningful.”

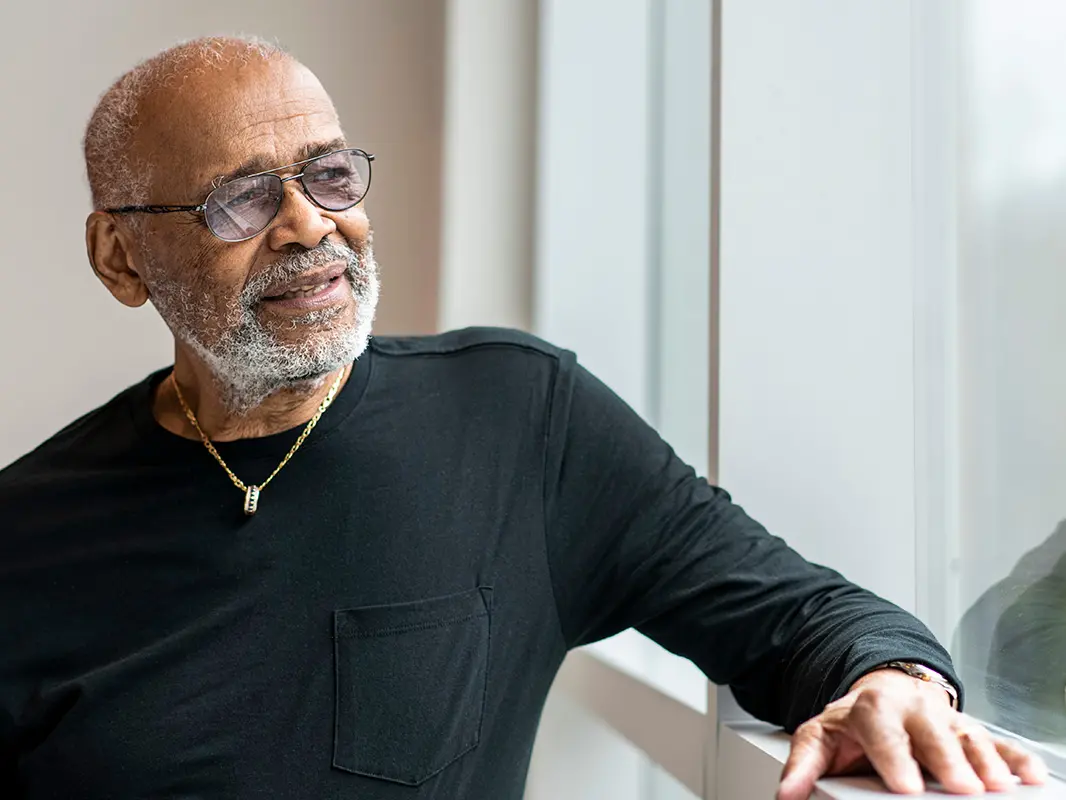

Peggy Mills ’80, MA ’93, a retired teacher of adapted physical education and owner of Valemee Fitness, developed a unique exercise system to help adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities work out independently. The study validated that her approach works.

School systems provide those with disabilities educational services, including exercise and recreational outlets, until they’re 22. After that, they are on their own.

“When you’re out of school, recreational opportunities, social circles, that responsibility falls on the family, and one of those aspects is physical fitness,” says Barry Halpern ’81 MD, whose 35-year-old son Max participated in the study. “With Max, when he was a teenager he was fit and trim. But through his 20s and 30s, he put on 25 pounds. It’s significant.”

And common. Adults with IDD have some of the highest rates of obesity, diabetes and chronic heart disease, to the point the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention and the United States National Physical Activity Plan have identified the population as a target community for whom to promote physical activity.

Though many like Max Halpern, who has Down syndrome, may belong to a gym with a parent or caretaker, most gyms aren’t equipped with trainers and systems to accommodate people with these special needs. Because of that, few members of the IDD population are at these gyms, leading to diminished social opportunities.

While Valemee patrons had friends and people who knew and worked out with them, most gyms have none of those welcoming faces for this community. Dr. Halpern says often other gym’s clients get worried or uncomfortable when Max is working out on his own. And for people with IDD, it’s intimidating, says Zayne’s mother, Gwen Harshaw.

“A major barrier is people’s attitudes at the gym,” says Harshaw, who also is program director for the Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence (OCALI). “If people without a disability feel anxiety about going to a gym, people with a disability — oh my goodness.”

Ohio State’s Carmen Swain ’97 MA, ’07 PhD monitors as Dujmovic, right, demonstrates a move for a study participant at Valemee Fitness in January.

“Seeing Carmen and Anthony come in was wonderful because they didn’t have experience with this population,” Mills says. “It wasn’t a special education professional coming in. It was someone from the world of fitness saying, ‘Everyone deserves optimal fitness. Let’s measure whether or not we can make a difference in their lives.’”

The study did exactly that.

For eight weeks, 25 IDD participants with no background in Mills’ system exercised at Valemee twice a week. Across the board, results showed increased fitness, independence and self-efficacy, meaning they came into the gym and worked out with less supervision over time.

Participants also overwhelmingly said they would continue exercise and nutrition programs, whether at home or through community opportunities. And though Mills’ gym has since closed, she is spreading the Valemee system throughout gyms in Central Ohio with eyes on going national, so that more gyms have trainers fluent in her process.

“It was a great first step. Zayne really enjoyed it,” Harshaw says. “I want him as healthy and happy as possible, but he’s a grown man. It hasn’t been easy to motivate him.

“Being sedentary is horrible, it leads to lifelong problems. When you’re a parent to someone with a disability, your greatest fear is, what’s going to happen if I die? It’s overwhelming and part of that fear is physical health.”

Zayne says the study was life changing.

“I’m excited to keep doing this and more confident in myself. I want to make big changes,” he says. “It was so much fun, I felt like I achieved something. It’s so much better than sitting in front of the TV, stuffing my face.”

Dujmovic, left, fist bumps Zayne Harshaw after the study participant walked 20 laps at the gym. The study, Harshaw says, “was so much fun, I felt like I achieved something.”

Swain says the study proved the Valemee system works. She has been invited to give talks about it at national conferences and is also working with Dujmovic to publish study results in academic journals.

“I love research, but one of my big hang-ups is research sits on a shelf,” Swain says. “It’s only read by science geeks who open a journal. It’s often not translated to practice. But this study has the opportunity to be put into practice.”

That’s important because studies and research on this population’s fitness problems are lacking; it can be challenging for researchers who don’t have a background in special education to work with people with IDD. Swain said writing the Internal Review Board proposal, required for all studies involving people, was one of the most difficult she has completed, and for good reason.

“The IRB’s job is to make sure, with human research subjects, you aren’t taking advantage of anyone or exploiting anyone. And that’s a very good thing. However, because this population has so many challenges, they’re rarely used in health-related research, which is such a detriment to them.”

Even with Mills’ guidance, Dujmovic says, putting the study participants through the exercise testing — making sure they did all the workouts safely — required much more patience and instruction than he was used to. However, it was an experience he’ll never forget.

“The first week of testing, I sat in my room and cried every single night, seeing the challenges they go through every day,” Dujmovic says. “But their resiliency blows my mind. I’ll keep that with me forever.

“There’s a huge gap between the opportunities people with intellectual disabilities have and what everyone else has,” he says. “We need to fix that.”

An inspiring partnership

Carmen Swain and Anthony Dujmovic discuss how mentorship is at the heart of their research success on Ohio State’s new podcast, Now at Ohio State.