In soil, Rattan Lal sees the future of us all

Soil is key to feeding people, preserving land and improving Earth, a message Lal has been spreading for 60 years, since as a boy in India, he seized a chance to learn.

The thin man in the Ohio State ballcap hunches down near his home garden, in the backyard with the two Buckeye trees.

He’s holding a clump of dirt.

“No, no. Not dirt,” he says. “This is soil. Soil is not the same as dirt. Soil is a living entity. That’s the part we must understand.”

His hands are cupped, as if holding a baby bird. He gazes in admiration, points to roots and a worm. He tells us a tablespoon of soil contains billions of microorganisms.

“Soil is one. Indivisible. Interconnected,” he says. “Soil is the basis of all terrestrial life. Every living thing on the planet depends on it, and yet this material is underappreciated and unrecognized.”

His face is wrinkled and weathered, a testament to years spent researching in the fields, forging wisdom about our place in the world.

“We belong to nature. We belong to soil,” he says. “Therefore, we have a duty and obligation to soil.”

The sun is setting, but he’ll be in his office tomorrow at 5 a.m., as usual.

He has researched soil for five decades on five continents, traveling to 106 countries to spread a message. But more work must be done to spread understanding about the critical role of soil in the health of the planet.

“That challenge,” he says, “is my motivator, my driving force.”

Video: Rare earth

In this six-minute video, Rattan Lal and his team share how science he’s developing helps to richen soil, improve yields and improve sustainability. (Video by Andrew Ina)

‘He has very high expectations of himself’

Walk with Dr. Rattan Lal ’68 PhD, Ohio State Distinguished University Professor of Soil Science, and he’ll always open and hold the door for you and others to pass first.

“Please,” Lal says, waving you forward as if hosting a dignitary.

There is one door that Lal makes certain is always open in his 33rd year as a faculty member in the College of Food, Agricultural and Environmental Sciences.

“I can go to Dr. Lal’s office and he will make time,” says Nall I. Moonilall ’15 MS, one of Lal’s six graduate students. “He’s very personable. He’s human. He’s someone you can interact with. He’s not just a robot scientist.”

Nor is Lal an ordinary scientist. Thomson Reuters has long listed him among the top 1 percent of the most frequently cited agricultural researchers in the world. In 2007, Lal was recognized for his contributions to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which shared the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize with former U.S. Vice President Al Gore. In April, Lal was awarded the Japan Prize, one of the most prestigious honors in science and technology. And he is the winner of the 2019 Alumni Medalist Award, the highest honor bestowed by The Ohio State University Alumni Association.

Such status suggests that Lal deserves a gilded lair, but he sits behind an ordinary metal desk in Kottman Hall, Room 422B — a painted cinder-block room measuring 9 feet by 12 feet.

“My office is fine,” Lal says. “The office is in proportion to your contributions.”

His modesty also masks a fierce inner drive. Three heart attacks have not slowed him, and praise from international peers has not inflated him. He has more speeches to give, papers to write, conference calls to join, classes to teach, research to conduct and students to mentor. “This is who he is,” says Sukhvarsha Sharma ’97, his wife of 48 years. “He has very high expectations of himself. He wants to make a difference in the environment, and through that, make a difference in peoples’ lives.”

Rattan Lal harvests vegetables in his home garden. (Photo by Jo McCulty)

That determination is why Lal arrives at his office before dawn during the week and at 7 a.m. on weekends, working for about 12 hours daily. His wife says his last day off was five years ago when he was hospitalized after his fourth heart surgery, when a pacemaker was implanted. He toils nonstop at age 75. Well, he’s probably 75.

“Nobody has a record of my date of birth,” Lal says. “When I was a boy in India, the teacher said, ‘How old are you?’ My dad said, ‘Oh, I think we came from Pakistan when he was 5 years old, but you can put one year less. He’s 4.’ I consider September 5 my birthday because it was my first day of school.”

From such a murky past, Lal has ascended to the summit of scholarship, with improbable ties to Ohio State dating to his teenage years in India, where his village home lacked electricity. He became the brightest light in soil science by devoting his life — spending nearly two decades in Nigeria, a nation caught in a cycle of violence and political upheaval — to studying how no-till farming can help address the global issues of climate change, food security and water quality.

“There is no more revered, more impactful soil scientist in the world today,” says Ohio State President Michael V. Drake. “You’re at the tip-top of science when you make discoveries that change the way the world’s experts in your field think about the work they do. That is what Dr. Lal has done.”

“There is no more revered, more impactful soil scientist in the world today,”

In the early 1990s, Lal co-authored the first documented report that showed how restoring degraded soil through the sequestration of atmospheric carbon dioxide not only improved the soil — scientists including Lal had long hypothesized this — but it also helped to combat the rising levels of carbon dioxide in the air. He has since added to that discovery through research in partnership with students at the Ohio State Carbon Management and Sequestration Center, which he founded in 2000 and still directs.

“What is most significant about Dr. Lal’s research is that today the sustainability of the soil resource regarding soil-carbon sequestration is an issue on the climate change agenda,” says Laura Bertha Reyes Sanchez, professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico and president-elect of the International Union of Soil Sciences.

Lal served as president of that 60,000-member group in 2017–18, but that’s just one line on a vitae longer than a Russian winter. The details should be in neon. Ponder this one: His writings have appeared in 95 books and 950 journal articles — facts he won’t trumpet without prodding. “He doesn’t expect that you know who he is or what he’s accomplished throughout his research career,” says Moonilall.

Rattan Lal works with graduate students and researchers from the university’s Carbon Management and Sequestration Center in a plot at Waterman Agricultural and Natural Resources Laboratory. Lal founded the center in 2000, and earlier this year he donated $540,000 — his full proceeds from the Japan Prize and two other honors — to Ohio State to support the center’s research. (Photo by Jo McCulty)

Occasionally, however, Lal lets slip a nugget of information, buried in his quiet, deadpan delivery, that makes you stop and think, “Wait, did he just say that?” Here’s a good one: “I was talking to Mr. Gore for an hour today. He called.”

Lal’s expertise is drawing even more worldwide recognition. He was the first Ohio State scientist and first soil scientist anywhere to win the Japan Prize in its 34-year history. The prize recognizes scientists and engineers from around the world for outstanding achievements that both contribute to the advancement of science and promote peace and prosperity for mankind. In 2018, Lal was awarded the Glinka World Soil Prize from the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization as well as the World Agriculture Prize from an international confederation of higher education associations.

“The Japan Prize and other awards are a recognition of the work of all my colleagues, the students, the visiting scholars, the post-doctorates and research scientists,” Lal says. “I clearly did not get those awards on my own. It is my association with Ohio State that makes me a very unique person.”

Lal’s appreciation for Ohio State goes beyond words. This summer, he donated all $540,000 of his total prize money from the three awards to an endowment supporting the university’s Carbon Management and Sequestration Center. He has pledged to contribute another $460,000 if Ohio State can raise $4 million more.

“That’s exactly what you do with soil: You make an investment to restore,” Lal says. “You always want to leave something behind, but the best thing is not necessarily the money. The best thing to leave is an idea, a concept that will go over generations.”

For Lal, a father of four — each one an Ohio State graduate — and grandfather of four, leaving behind the knowledge that healthy soil management can improve the world’s future is tied to his own past.

The seed for his ideas came from growing up a poor refugee in Punjab, in Haryana state, India. There, Lal saw others in need, how soil affected their lives and connected everyone. And it’s where his determination to help others found an outlet through doors unexpectedly opened by people from a far-off place.

“From 15 years of age,” Lal says, “all I knew was Ohio State.”

Caring about things bigger than himself

There are times when Lal looks like a symphony conductor as he speaks, his voice accompanied by slowly moving hands, as if words about soil were notes in a musical sonnet.

In those moments, your eyes might fall on an ancient symbol in faded blue ink on the back of Lal’s right hand. He thinks he was about 8 years old when a stranger on a bicycle came to his school in India offering cheap tattoos. The boy couldn’t resist. Nearly seven decades later, he regrets his choice.

“I would not get it done now,” Lal says. “But a small decision about a tattoo, that’s very little in importance. Decisions about soil are very, very important. Those are decisions that influence other people’s lives and have very long-lasting impact.”

The impact is intensifying because the world’s population is projected to increase nearly 50 percent in the next 80 years — an ominous forecast that Lal tells Ohio State students on a summer afternoon while lecturing in an Introduction to Soil Science class.

“How do you feed 10 billion people? One child going to bed hungry anywhere is one too many.”

Humanity, Lal warns, is facing a dire necessity to advance food security by protecting finite, fragile soil resources. “Agriculture and soil are, can be, and must be a solution,” he says, clasping and shaking his hands for emphasis.

In that moment, you could see Lal’s tattoo, an ink version of the symbol for om, considered the most sacred of mantras in his Hindu religion. Through the word’s three distinct sounds — “a-u-m” — the speaker is meant to understand the essence of the universe: Everything is connected. Om is the sound of Lal’s life.

“There’s just kind of an equanimity, a sense of mental peace, about him,” says Ellen Maas ’17 MS, one of Lal’s current doctoral students. “His manner is not one that is focused on himself. He just cares so deeply about humanity and the planet. He finds an inner strength in caring about things bigger than himself.”

Lal’s family experience shaped his worldview. The youngest of three, he was raised by his father after his mother died of an illness when Lal was 3 months old. When India was partitioned to form Pakistan in 1947, his family fled as refugees to the Indian village of Rajaund, about 120 miles northwest of New Delhi. They left a 9-acre farm and settled on one totaling only 1.5 acres, a change that marked Lal with a different tattoo, just as permanent but invisible.

Lal and Sukhvarsha Sharma, center, shown while the young family lived in Nigeria, have been married since 1971. She earned a bachelor’s degree from Ohio State in 1997, and the couple’s four children are all graduates of the university. (Photo courtesy of Rattan Lal)

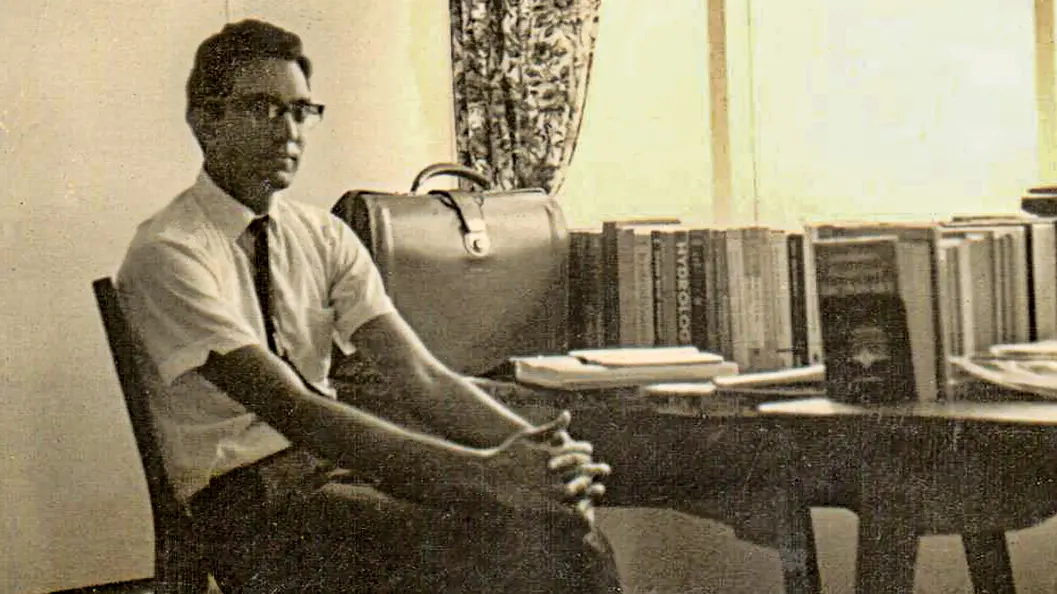

When Lal studied for his doctorate at Ohio State, he lived in this apartment on Ninth Avenue in Columbus. He was 7,300 miles from home and a world away from the one-room house where he grew up. (Photo courtesy Rattan Lal)

“It taught me that the land is very precious,” Lal says. “You cannot let it waste. Your life depends on it. Our land was so small, but it was not a unique situation. There are right now in the world about 600 million farm families that have less than 2 acres. In a way, what I do and what I think relates back to those people and my experience.”

Lal helped grow rice, wheat, cotton and sugar cane on his family farm. But unlike his siblings, he also was sent to school by his father. The child felt chosen, obligated to make good on a privileged opportunity. In 1959, his diligence and excellent grades met Ohio State in serendipity: He enrolled at the Government Agricultural College and Research Institute (which became Punjab Agricultural University his senior year). Ohio State had helped establish the institute only four years earlier.

“As somebody who had not been to any other college before,” Lal says, “Ohio State was my example of international education, teaching and research. It meant quite a lot. Ohio State had faculty members there teaching as well as advising how to develop curriculum.

“One of the professors, Dr. [Dev Raj] Bhumbla, had just returned with a PhD from Ohio State, and he started teaching a soil class. I was in that class. My best subject was botany, but he told me to go into soil science. In fact, he recommended my name to faculty at Ohio State to be a student there.”

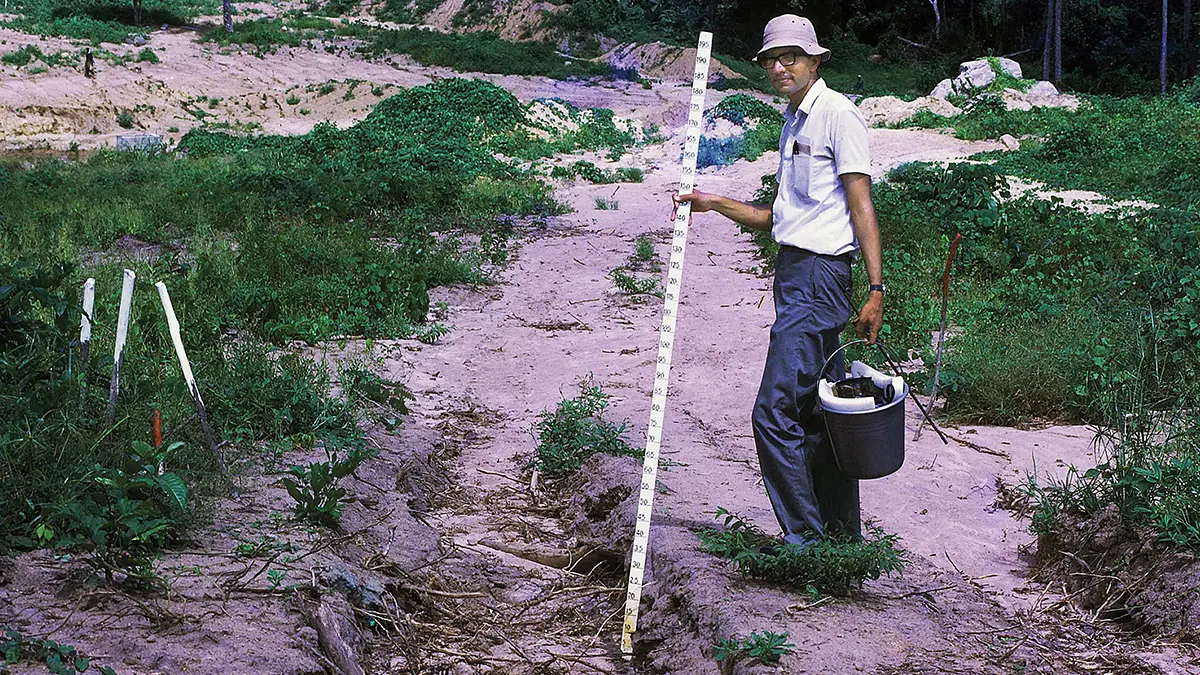

At the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture in Nigeria, Lal works to develop alternatives to Africa’s traditional farming methods, which erode precious soil. (Photo courtesy of Rattan Lal)

In December 1965, Lal boarded a plane for the first time and traveled alone 7,300 miles to pursue his doctorate at Ohio State. He brought along an insatiable hunger to succeed. At Punjab Agricultural University, he had run four miles — yes, run them — to school from home every day, studied by the light of a kerosene lamp, sometimes held up by his grandmother. He found an agricultural book in the library so essential that he spent two months hand-copying it to have his own edition. “Nothing can be achieved without the strongest possible desire to achieve it,” Lal says.

His desire and degree mixed to fuel a career trek around the globe. Ohio State connections landed him research jobs, first in Sydney, Australia, for a year, and then in Nigeria, where the Rockefeller Foundation asked him to set up a soil science laboratory at the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture. Lal and his wife — only a year into their arranged marriage — went in spite of a bloody civil war. They stayed 18 years, even as three Nigerian governments were toppled by coups.

“Once, I was at the house of a general,” Lal says. “He had invited me to come talk about suggestions to control soil erosion. Two days later, he was hanged and his family shot. People have said if I was there when they came, I would not be here today.”

One moment can make a difference. So can one person.

This is why he accepts invitations to speak about soil, whether the audience is filled with heads of power or young burgeoning minds.

“The students are ambassadors of Ohio State,” Lal says. “They represent us. They carry on the work that we do.”

There are 22 students in this day’s class. Lal speaks to them without notes, standing next to a podium, hand in pocket. His tone is measured, but his message linking soil management to the nourishment of humankind is urgent.

“The story has to be told in a language that farmers and policymakers understand and can relate to. That’s critical,” Lal says. “That’s going to take education. We have to change opinions in a humble way. That falls on your generation.”

‘Our duty to carry the torch’

The thin man in the Ohio State ballcap hunches down in a field at Waterman Agricultural and Natural Resources Laboratory. A scorching summer sun beats down without mercy.

Sweat is on his face, but so is a smile.

“This is the best thing in life,” Lal says. “It is a privilege and honor to work with students. I learn from them, for sure, and I hope that they learn something from me.”

Five graduate students and researchers — including one from China and one from Algeria — at the university’s Carbon Management Sequestration Center encircle him. They’re examining the soil from a test plot.

“We work hand in hand with Dr. Lal,” Moonilall says. “He looks at us as colleagues rather than students. He expects you to think more critically in terms of, ‘What’s the application or implementations of what you’re learning? How could you propel the science forward and help farmers and people across the globe?’”

As an undergraduate in India, Lal thought he’d become an agricultural extension agent in his home country. Instead, his extension is worldwide. Since 1968, Lal has mentored 115 graduate students and 54 postdoctoral researchers, and he’s hosted 175 visiting scholars, who work with him for months or even years, from around the world.

“Ohio State has been a great institute that has provided me the environment in which I have been able to thrive and contribute knowledge to address global issues,” Lal says. “Many of my students now have very high academic positions in their own country, which is a matter of great pride for me. Through those positions, they influence the thinking and philosophy of their colleagues.”

Lal’s current students feel that sense of empowerment. “I think it’s our duty to propel this forward and carry the torch,” says Moonilall, who joined Lal at Ohio State in 2013 and is in the midst of writing his dissertation about reviving the productivity of degraded soil in central Ohio.

Lal speaks with scientists at United Nations University in Dresden, Germany. (Photo courtesy of Rattan Lal)

Not that this guiding light is nearing retirement at age 75 (or so). Lal is teaching two classes, advising 11 students, writing journal articles and another book, and spreading the word about soil.

In July, Lal was at the Ohio Statehouse telling legislators that soil must be protected by a clean soil law in the way government regulates clean water and air. This year alone, Lal has attended scientific events in 18 states and nations, including in South Africa and locations in Europe and Asia. As always, there is more work to be done, and an enduring spirit to meet it.

“Right now, soil is not on the political agenda of the policymakers,” Lal says. “That is why soil scientists have to be proactive. It’s going to take patience and perseverance.

“I’m a born optimist. If I wasn’t an optimist, I wouldn’t be here. Imagine the background, where I came from, a place which is probably the most remote ever. It required an optimist to overcome those obstacles. I’m not giving up yet.”