In praise of civility and peace at the kitchen table

Michael Neblo, professor of political science, is here to teach us a few things about how to have civil conversations when political opinions differ.

Michael Neblo, professor of political science, chats with a student at a recent event. Neblo’s mission is to better connect voters and their representatives. (Photo by Jo McCulty ’84, ’94 MA)

Michael Neblo grew up with a mom who voted for Ronald Reagan and a dad who was a Teamster, neither of them timid about talking politics — respectfully.

When Neblo, now an Ohio State professor of political science, began his college studies, he was shocked to learn faculty thought little of political discussions among people like his folks. These polar observations — robust debate at the dinner table and dismissal of those conversations by his teachers — made Neblo a ceaseless advocate for civil political discourse, aka enabling clear and open communication between voters and elected representatives.

He didn’t set out to do this in one of the most polarized moments in U.S. history. But it’s happened, and it’s a great time to learn to talk openly and respectfully about politics and policy. You agreed and asked Neblo some of the questions on your minds.

-

What is the best way or where is the best place to find evidence-based answers to questions about economic and social policies? — Kinnison Edmunds ’19 DDS

Paradoxically, the information revolution can make it more difficult to find the information that we need to engage in public discourse or to vote according to our values. The sheer volume makes it hard to know where we should invest our attention. And even if one’s information sources happen to be reliable and evidence-based, it is difficult to know that they are. Efforts to sow confusion with fake news or partisan spin abound.

My go-to source is the Congressional Research Service (crsreports.congress.gov), which produces rigorous, timely, nonpartisan research on a huge range of topics. This underutilized gold mine has more than 7,000 searchable reports covering two dozen subject areas. Most reports are surprisingly readable and free to the public.

-

Is there another time in U.S. history that closely parallels the polarized political environment we see today? — Justin Vance ’07

The 1850s saw the country splitting into factions, with angry, polarized citizens losing trust in their government and social institutions. One of the two major parties looked like it might break apart. Wild accusations flew, and each side increasingly saw the other as enemies rather than merely rivals. New communication technologies accelerated the strife and perhaps abetted people retreating into partisan echo chambers.

As much as this description might sound unsettlingly familiar, I hesitate to say that the antebellum United States “closely parallels” our situation today. I do not think that we are on the brink of civil war, though I do believe that our political divides run deeper than they have at any time since. In my view, the problem is not mainly that we are more polarized on the issues. We should all expect disagreement, and the best answers are not always found in the center. I am much more troubled by the large increase in what political scientists call “affective” polarization — that we distrust and dislike each other because of our political differences. Affective polarization poses more of a danger because fear and hatred tempt us to treat our rivals as enemies, as illegitimate threats to the republic rather than neighbors who simply see things differently.

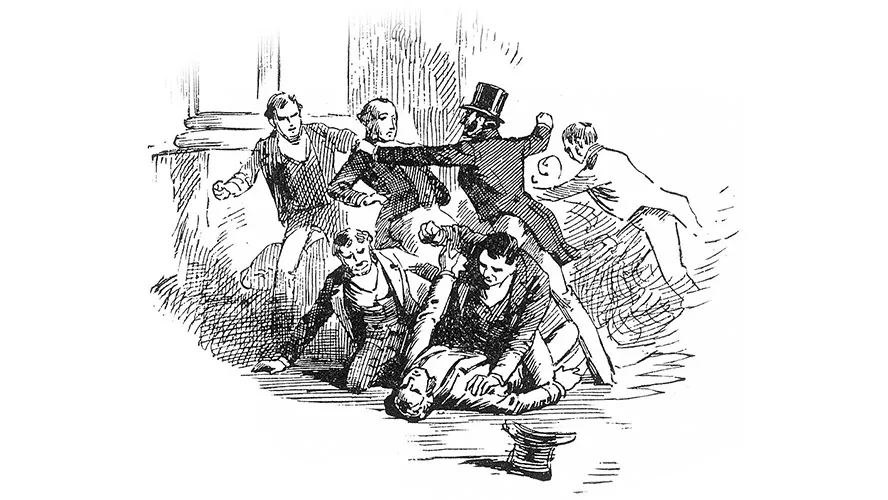

It was not unusual for arguments in Congress in the 1850s to end in fisticuffs. This cartoon depicts a fistfight on the House floor in 1858 over a debate about slavery. (Library of Congress)

-

Is social media intensifying the current divide? — Jerry Turner ’97

As I noted, the U.S. was even more deeply divided in the antebellum era. But the fact that our current situation comes in second should be cold comfort. One does not want to be next in line after the horrors of slavery and America’s bloodiest war. I should also note that the media at the time (especially newspapers) were often explicitly partisan, with no distinction between their news and opinion functions. So I am not sure that digital social media are really the culprit for us. Several excellent research teams have studied the extent to which social media are really aggravating filter bubbles and driving polarization. The evidence so far is mixed, suggesting that social media are certainly not the only (and are maybe not even the primary) driver of our increasing divisions.

We should also remember that debates on the floor of Congress used to end in brawls and duels. Conflicts with the media were so intense that a representative from Virginia once nearly bit off a newspaper editor’s thumb over unflattering coverage. And neighbors, even brothers, literally took up arms against each other. As ugly as things often seem to get now, we are still a long way from the chaos and violence that plagued our social and political institutions then. With hard work and goodwill, we can recover from our current state as well.

-

As children we were taught not to discuss religion or politics. I think it might be better if we could discuss these things in a civil way. How can we teach our children to be able to do this? — Mary Thomas ’53

I was taught this maxim as well, though my mom included the qualifier “in polite company” — that is, among people you do not know well and who are meeting for a purpose other than such discussion. I actually think that is sound advice so far as it goes: Better to refrain from starting that political argument with the people you just met at your boss’ daughter’s wedding. But I strongly agree that we need to learn to discuss controversial issues civilly, and not just with people we know well. Several organizations are devoted to this project, such as the National Institute for Civil Discourse. Many schools (from kindergarten all the way up to universities) have programs designed to foster good civics skills and habits. But coverage is spotty, and the temptation is to cut such civics investments in favor of more immediate benchmarks like test scores in math and reading. That said, I think Ohio State takes its motto, “Education for Citizenship,” quite seriously in terms of research, curricular initiatives and extracurricular activities. For example, a program I direct, the Institute for Democratic Engagement and Accountability (IDEA), sponsors work in all three of these domains.