Scenes from the sandbox

Take a look inside the Pelotonia Research Center, Ohio State’s new scientific hot spot, where teamwork, creativity and innovation flourish.

“We needed to get people together who are supercreative and who want to be part of something bigger than just their own science, people who are in different disciplines that may not know each other and may not even be thinking about the same problem. We needed them in an ecosystem.”

The Pelotonia Research Center—one of the largest capital projects of Time and Change: The Ohio State Campaign, costing $227.5 million to build—opened in June 2023 to provide that fertile place where interdisciplinary ideas and expertise cross-pollinate with a welcoming of new partnerships between academia and business. It’s a scientific hot spot where working researchers, clinicians and students make our university’s ideal real. You see creativity enhanced by connectedness, resulting in new ideas and new answers.

Let’s take a look.

At the Pelotonia Institute for Immuno-Oncology on the third floor, Dr. Elshad Hasanov (second from right) leads a team investigating why kidney cancer often spreads to the brain. Here he holds a lab meeting with (from left) PhD student Peng Li, incoming PhD student Mostafa Ali, Dr. Merve Hasanov (his wife and collaborator) and postdoctoral fellow Alessandro La Ferlita.

When he enters the PRC, Dr. Elshad Hasanov doesn’t just see fellow cancer experts. As he heads upstairs to his laboratory, he also encounters biologists, neurologists, pharmacists, veterinarian researchers, psychologists, industrial designers and various types of engineers. “You realize, wow, this is exactly where the groundbreaking work happens,” says Hasanov, an oncologist and immunologist at Ohio State.

This scientific tapestry clarifies Hasanov’s own research mission—to find new ways to help patients as soon as possible—and surrounds him with a unique potential for such novel discoveries. “Being close to them makes it very feasible to enrich the collaborations,” he says.

Proximity also provides confirmation of what Hasanov saw in Ohio State when he was recruited by the university two years ago from Houston, Texas, where he was serving as a medical oncology fellow at the MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Hasanov saw Ohio State climbing research rankings, breaking its own records for research spending and building its roughly 350-acre Carmenton district, part of a vision for a community shared by the university, the nonprofit state economic development group JobsOhio and the city of Columbus. And he saw the 305,000-square-foot Pelotonia Research Center—a glass and gray-trimmed anchor of Carmenton—and the next-door Energy Advancement and Innovation Center, which opened in November 2023 and now houses his clinical office, a brief plaza walk from his lab.

“The institution is at a growth curve,” says Hasanov, recipient of a 2021 Kidney Cancer Association Young Investigator Award for his immunology research. “You realize that if there are buildings coming together, those buildings need to be filled in with science, discovery and patient care. You feel like there are good opportunities here to cultivate new ideas and let them grow.”

Hasanov left Houston in 2023 to join the Pelotonia Institute for Immuno-Oncology, created by Ohio State four years earlier to study the immune system’s role in fighting cancer. His lab and surrounding institute are on the PRC’s third floor, one above the university’s Comprehensive Cancer Center-CURES.

Although the Pelotonia Research Center is named in recognition of nonprofit Pelotonia’s collaboration with Ohio State, the building’s focus includes more health and well-being challenges. Floor 5, for example, has labs to address heart issues and women’s health. Labs targeting food insecurity are on ground level, conveniently across West Lane Avenue from the university’s Waterman Agricultural and Natural Resources Laboratory.

Instead of designing floors for a certain college or department, they were constructed so that the center’s multiple laboratories—organized into “neighborhoods”—foster connection and community. “The open space and building’s infrastructure allows that we don’t sit in silos,” Hasanov says. “We know who is working in this building. The fact that you’re located in the same proximity basically smooths the interaction.”

Hasanov heads a diverse research team searching for answers to why kidney cancer often spreads to the brain and how to slow or stop metastasis. His collaborators have backgrounds in machine learning, clinical medicine, biology, computational biology, epigenetics and bioengineering. They’re from eight countries, and their combined work is set to launch a new clinical trial.

“You’re learning from everyone’s strengths,” Hasanov says. “You’re also bringing your own strengths to the table to help others understand cancer and tackle it. I’m lucky to be here. With these resources, we’re able to help patients nationwide.”

Picture the width of a human hair. Now imagine something being 10,000 times smaller. That’s the size of a nanodomain, a cluster of proteins found in a cell membrane.

Rengasayee Veeraraghavan can see that minuscule structure inside cell molecules by using state-of-the-art equipment for light and electron microscopy. “With the newest technology, I can see down to 2 nanometers,” he says.

Nanometers are units of measurement. A sheet of paper is about 100,000 nanometers thick. “What looks like a random cluster of molecules, I can see detail in there about how they’re organized and put probes on different parts of them so we can track those domains individually,” says Veeraraghavan, a cardiac physiologist and associate professor of biomedical engineering at Ohio State.

Life depends on those details, each important to the health of a heart. Heart diseases cause hundreds of thousands of deaths each year. That’s why Veeraraghavan is glad to see biomedical engineer Seth Weinberg in a different lab on the same fifth floor. Partnership is steps away. “The reason we need to work with Seth is that his lab is really pushing boundaries, inventing new ways of computational modeling,” he says.

Thomas Hund, director of the Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute, collaborates with a team—led by Veeraraghavan and Weinberg—from the colleges of Medicine, Pharmacy and Engineering to seek preventive therapies through new understanding of cardiac arrhythmia, a condition that causes an irregular heartbeat, leading to different heart diseases.

The heart beats in a precise sequence involving 12 billion muscle cells. Thump. Thump. Thump. Nanodomains contain a handful of key ion channel proteins that contribute to the spread of electrical signals from cell to cell in the heart. Thump. Thump. Thump. What is it about those proteins that sometimes causes signal disruption?

Weinberg, Veeraraghavan and Hund earned a five-year, $3.68 million National Institutes of Health R01 grant in 2023. They’re combining computational and experimental research to dig into what’s happening in the heart at the level of individual proteins. “It’s an innovative approach,” Hund says.

In photo, clockwise from left: Dr. Thomas Hund, grad student Madison Ammon, undergrad Austin Elliott, Research Associate Mei Han and Associate Professor Rengasayee Veeraraghavan (sitting) look at images on a high-powered microscope. The team works across disciplines to better understand cardiac arrhythmia and seek preventive therapies.

Hund purposely placed this targeted team, normally scattered across campus, together on the fifth floor at the PRC. The nanocardiology lab is adjacent to the computational physiology lab, separated by only a glass wall.

In photo: Elliott conducts research in the nanocardiology lab. A $3.68 million federal grant is funding the team’s research into what’s happening in the heart at the level of individual proteins.

“Collaborating together in one space enables us to have conversation to make sure we speak enough of the same language,” says Weinberg, associate dean for research in the College of Engineering and professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering. “That’s definitely a really big challenge in all interdisciplinary research. We want to make sure that we speak enough of the same common vocabulary that we can learn from each other.

“Experiments are being performed 20 feet down the hall, so collaboration is very natural. Folks from our research group will sit in and observe experiments and truly develop an appreciation for where the data comes from. We can start to get a deeper understanding of the system we are studying. It allows us as computational modelers to develop a better intuition for what are the important features for our model to capture.”

Hund says modeling of cardiac electrical signaling in groundbreaking detail opens possibilities for designing new experiments and developing life-saving treatments for cardiac arrhythmia. All aided by a lack of barriers inside the Pelotonia Research Center.

“We’ve already seen an impact on our floor,” Hund says.

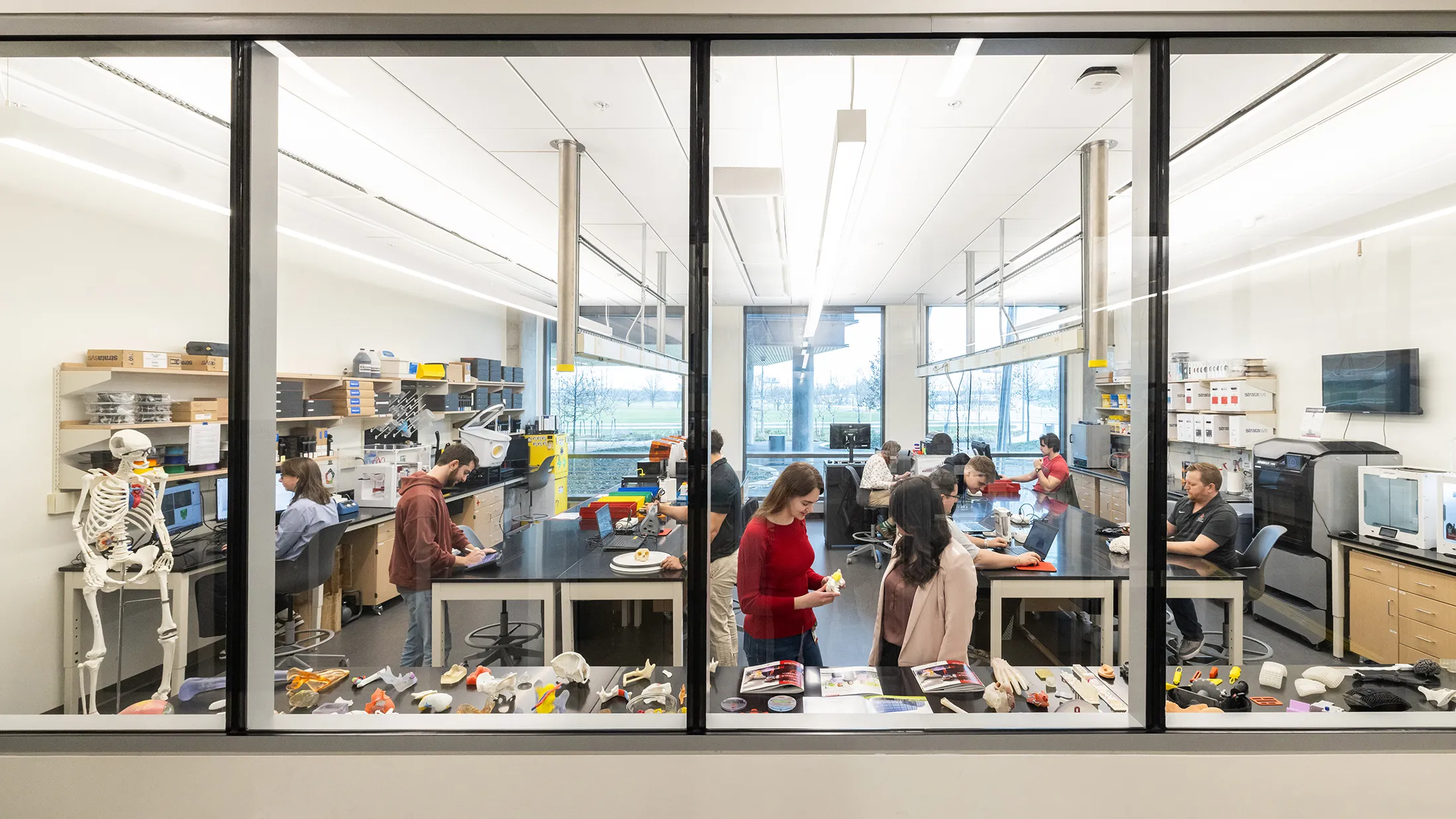

People on the outdoor public plaza sometimes stop to look through 8-foot-high windows into a PRC ground-level laboratory. They do the same from a hallway on the room’s other glass side [shown at the top of this story]. Often, they point.

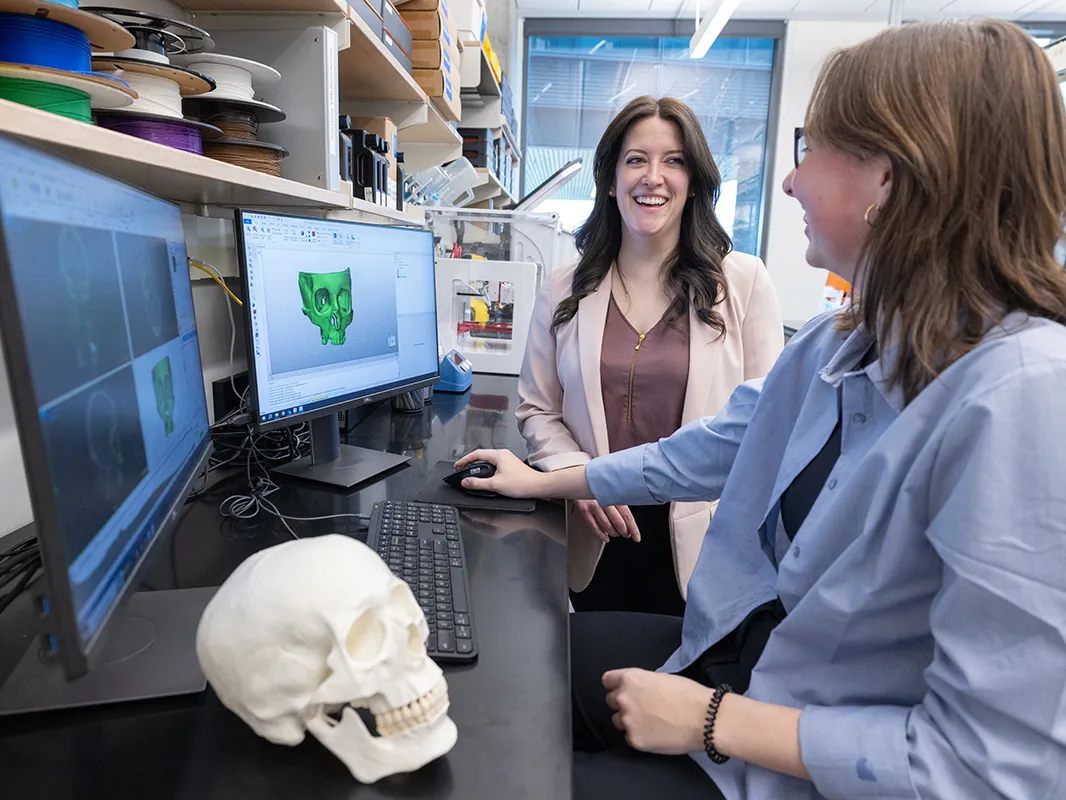

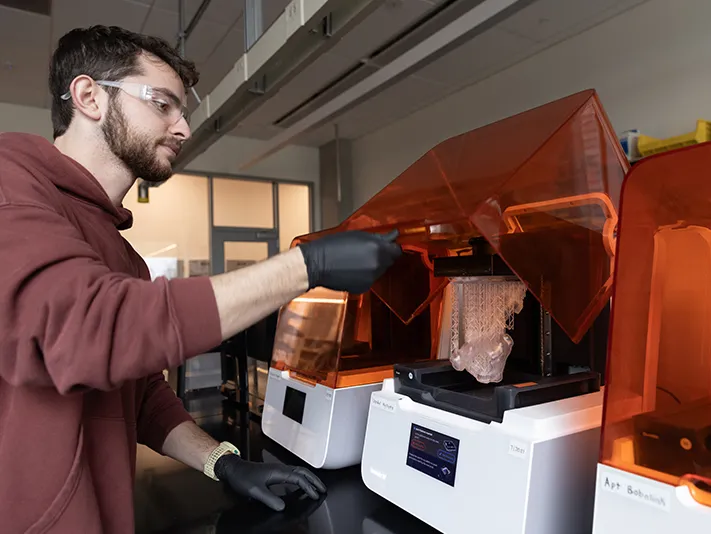

“I don’t know what they’re saying, but they seem very excited about what they’re seeing,” says Megan Malara ’14, ’17 MS, ’20 PhD, director of the Medical Modeling, Materials and Manufacturing (M4) Lab.

Ohio State’s M4 Lab also hosts tours, many with gawking elementary and high school students. Visitors pick up a brain or a heart or a jawbone—organs made on 3D printers by staff and students—from a demonstration table and pepper Malara with questions. “They’re very excited about what they’re seeing,” she says. “It’s a good showcase of the activity going on here.”

Such moments fulfill a Pelotonia Research Center goal of putting science on display. In the M4 Lab, you see medicine, advanced manufacturing and other materials-related research coming together to engineer solutions for new medical device technology that serves real-world needs.

Malara and her staff of five from the College of Engineering’s Center for Design and Manufacturing Excellence, collaborating with the College of Medicine’s Department of Otolaryngology, mentor 15 to 20 undergraduate students from aerospace, biomedical and mechanical engineering, and industrial design who participate in research and clinical projects.

The team uses numerous fabrication methods—including silicone molding and polymer filament and photopolymerization 3D printing—and other manufacturing capabilities. “Essentially, you design something 3D on a computer and the printer builds it layer by layer—think of it like a cake,” says Malara, an expert on tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Sometimes, team creativity helps medical professionals help patients. The M4 Lab has assisted in more than 200 surgical cases at The James Cancer Hospital in the past two years. Biomedical engineers are given a patient’s CT scans from which they design and make a matching anatomical model. Surgeons use those for procedural planning, as guides in the operating room, as well as for medical training and patient education.

In photo: Senior Hannah Cahill (right) works with Megan Malara ’14, ’17 MS, ’20 PhD on a 3D model of a skull in the M4 Lab.

The M4 Lab also designs and prototypes prosthetics, such as laryngectomy tubes and breathing and facial prostheses, customized for a patient’s needs. The process starts with designers making sketches, followed by engineers producing models of devices. Different skills tackling the same problem from different angles.

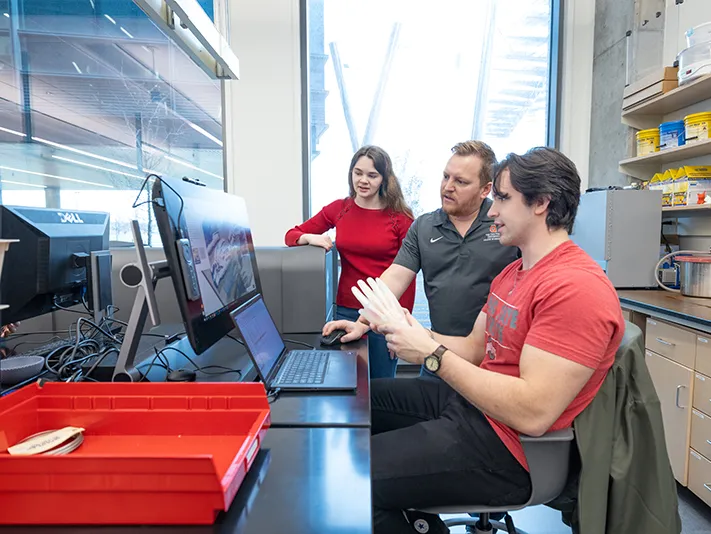

In photo, from right: Senior Ryan Eldridge, Senior Engineer Ryan Brune ’14 MS, ’16 PhD and Lead Engineer Rachel Herster discuss a model of a hand in the M4 Lab.

“This work is really important to me,” says Chipper Orban [shown here], an undergraduate and M4 Lab industrial designer. “I’m bringing in my skills to make something that helps people and improves someone’s life. I’m contributing to something bigger than myself.”

Orban hadn’t imagined working in a medical environment. Others also see new possibilities in the M4 Lab. Psychologists have received 3D-printed copies of more than 100 brains for help in a study of brain trauma. Tiny tools have been manufactured to aid cancer researchers in mouse testing.

“We’re getting a diversity of projects as they come in,” Malara says. “We’re kind of finding people that have all these interesting needs that wouldn’t know about us, and we wouldn’t know about them, if we had not been located here.

“What struck me in my first few months here is the number of rooms I was in where people said, ‘Yes, we want to do this new thing. We want to figure out how to make this new partnership.’

“Having people at a high level who say yes to moving something forward makes you feel we can make an impact at a faster pace.”

X. Margaret Liu ’05 PhD (left, with PhD student Tanvi Varadkar ’24 MS) leads Ohio State’s Center for Cancer Engineering-CURES program. “In this lab, I have space to do my research and expand my research,” she says. Her recent experiments successfully shrink brain and cancer tumors in mice.

Seven graduate students and their supervisor are bathed in sunlight as they meticulously conduct a lab test together at the PRC’s second-floor headquarters of Ohio State’s Center for Cancer Engineering-CURES program. “We like big windows and the natural light,” says team leader X. Margaret Liu ’05 PhD, professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering.

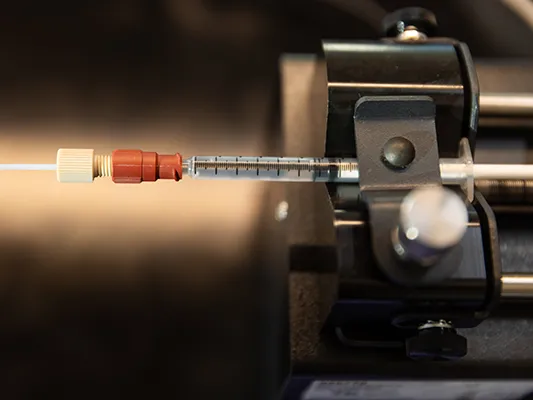

Tanvi Varadkar ’24 MS is using a syringe to draw a sample of cell tissue—embedded in a thin layer of vitreous water—to be pumped into a bioreactor harvester in front of her. On the same work bench is a $90,000 transmission electron microscope that’ll produce high-resolution images of the sample for computer analysis.

“This facility is great,” says Varadkar, a graduate teaching associate. “Everything you need is here, very systematic, well within your reach. It’s not scattered across campus at different sites. This building was made to ensure that we can perform our research very well and smoothly.”

Liu and Lufang Zhou, professor of surgery in the College of Medicine and in biomedical engineering in the College of Engineering, co-authored a study published in Cancer Journal in December. It showed how their combined research strategies produced a new gene therapy that experiments proved is effective at shrinking brain tumors and cancer tumors in mice. “That’s why we bring engineers together with different expertise,” Liu says.

Now the CCE-CURES project has Liu testing additional potential therapeutic effects of mLumiOpto, her team’s name for the innovative technique they developed to precisely deliver their gene therapy. Can this therapy also treat triple-negative breast cancer and other cancers? They seek that light in this day’s sunshine.

“This is the best facility to do cancer research,” says Liu, recruited from the University of Alabama-Birmingham to join CCE-CURES in 2022. “In this lab, I have the space to do my research and expand my research. I also have fantastic equipment here.”

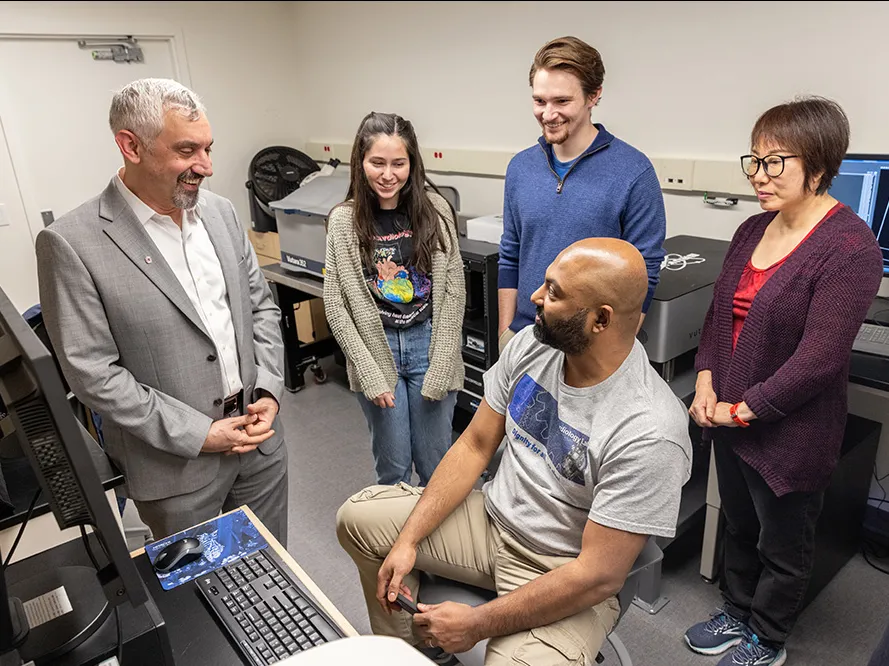

Some of that equipment is one flight of stairs down at the Immuno-Oncology Methods Development Program lab on Floor 1. “They bring their cells here, and we help them by running them on this instrument,” says Bob Davenport, a biologist and research specialist.

Davenport points to one of the lab’s two cell sorters, a device that isolates specific cells in a sample that were colored with fluorescent markers that bind to specific proteins, each in a different color of dye. They’re then passed through the lab’s flow cytometer, an instrument with several lasers that cause cell markers to emit light at different wavelengths, making it possible to separate two or more similar cell types for further experiments

In photo: PhD students in Ohio State’s Center for Cancer Engineering-CURES lab are (clockwise from right) Zhuoxin “Zora” Zhou, Jiashuai Zhang, Zhantao Du, Srijita Chowdhury and Natsorn Watcharadulyarat.

Back upstairs, Liu’s team is using sophisticated electron microscopy to read the light emitted by the cells in a test sample packed with their gene therapy. Next, specialized computer software for data analysis done on this floor will help reveal how the antidote affects the sample’s nanoparticles. “If it shows that the therapy kills the cancer, we can block the spread,” Liu says.

This evaluation process is necessary to understand the proper dosage of gene therapy needed when applied to a mouse model during in-vivo preclinical tests in the PRC’s basement. “It’s so convenient to work here,” Varadkar says.

Teamwork throughout the building is paying off. Liu says a venture capital company is talking with Ohio State about a possible partnership on her team’s gene therapy. Commercialization could lead to drug production to help people.

The ultimate hope is to move beyond treating cancer to finding an actual cure. “I believe we can do it,” Liu says. “It’s my career goal.”

Peter Mohler looks to his left through the glass-lined northwest corner of the Pelotonia Research Center and points to a similar looking gray building in Carmenton. “Right there is what’s called Andelyn Biosciences,” says the university’s research leader. Andelyn Biosciences, which began as a Nationwide Children’s Hospital startup, is a developer and manufacturer of gene therapies and opened its 180,000-square-foot manufacturing headquarters in Carmenton in June 2023.

“We need places like that once we know the science works,” Mohler says. “We have to figure out ways to get production so we can produce the solution in mass. Having them in our backyard is huge.”

The view to Mohler’s right is the Energy Advancement and Innovation Center (EAIC) and its rooftop solar panels high above the corner of Kenny Road and Lane Avenue. Building space is available for lease to outside companies for research partnerships with industry.

Photo: The Pelotonia Research Building (Photo by Katrina Norris)

It is already home to offices for Pelotonia, Ohio Life Sciences (the state’s industry association for the life sciences) and Koloma Inc., a startup pioneering sustainable hydrogen extraction technology that was co-founded by Earth Sciences Professor Tom Darrah, the company’s chief technology officer and director of Ohio State’s Global Water Institute.

In November, the Board of Trustees approved agreements to develop another 50 acres in Carmenton, including mixed-use development. Ohio State plans a commercialization and entrepreneurship center with two floors for the Center for Software Innovation and space for emerging companies.

That building will stand adjacent to the first university-owned structure in Carmenton, the PRC, where Mohler gazes through a window and sees time and change.

“We’re starting to see the building of the ecosystem,” Mohler says. “It’s growing. You can see it happening.”