This Ohio State lab helps people find their voice

The Language, Assistive Technology, and Autism Lab studies how to help nonspeaking kids and others express themselves using devices.

At a summer camp near her Ohio hometown, Meredith Suhr ’20, ’24 MA spent a couple of summers serving as an aide for a girl who was not able to speak. The pair forged a stronger connection after the girl began using a device that tracked her eye movements to help her communicate. Suhr loved the way it allowed them to get to know each other better and share jokes. “I was hooked,” she says.

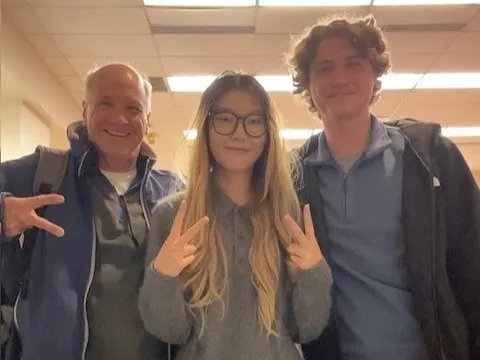

She’s now studying in the joint master’s and PhD program in the Department of Speech and Hearing Science and working with the Language, Assistive Technology, and Autism Lab, a collaboration among professors and students in the department. Partners include Wexner Medical Center and Nationwide Children’s Hospital.

The team shares a goal of helping people connect, just like Suhr did with her camp partner. They’re researching how to overcome communication barriers between those who struggle with speech, like some on the autism spectrum, and the world around them.

A major focus is augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) strategies. This is the professional term for anything from sign language or flash cards to apps on a tablet. One of the most recognized examples: famed physicist Stephen Hawking and his device with a computerized voice. “The goal is to help people develop authentic, independent communication,” says Associate Professor Allison Bean, co-director of the lab.

AAC helps people make friends, frame an argument, tap into the kinds of music they love and get some personal autonomy, says the lab’s other director, Clinical Associate Professor Amy Sonntag. The team explores both how the devices are used and how to make them more effective, which helps to shape the direction of future research.

In one project, Bean and Suhr examined how children use AAC devices at school. They found teachers often default to communicating with children about a limited range of topics—such as requests they might have or specific class activities. That becomes the main way kids get accustomed to using the devices, but there are many more ways and times in which the students could benefit from expressing themselves. “We communicate most often during the day to connect socially, to get questions answered, to comment—really to share this life experience,” Bean says.

Bean compares the process to language learning. If you take a Spanish class, or dabble in an app like Duolingo, you might pick up a lot of basic vocabulary about travel and passports. But if you don’t use that language in context, it quickly fades. It’s just words memorized for Spanish class.

While AAC research has increased in recent years, Bean says, there are still huge gaps in understanding who would benefit from devices and how to best use them. A growing number of people need help communicating, says Sonntag, who also works with clients in a clinical setting. Diagnoses of autism are increasing, she says, and people are surviving longer with diseases like Parkinson’s or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

In addition, support for people with language barriers often ends when they leave high school; Sonntag is working with Nationwide Children’s to help serve some of these clients, who may need support for life. Quite a few children with autism never develop strong language skills despite intensive intervention, Bean says. “We have a long way to go to really start to scratch the surface in this research,” Sonntag says.

Like Suhr, Sonntag was drawn to the field through a childhood connection with a girl who used AAC to communicate. “I’m so thankful to her and I always hope to honor her and help other people be able to accomplish what she did—and hopefully do even more.”