Grace in motion

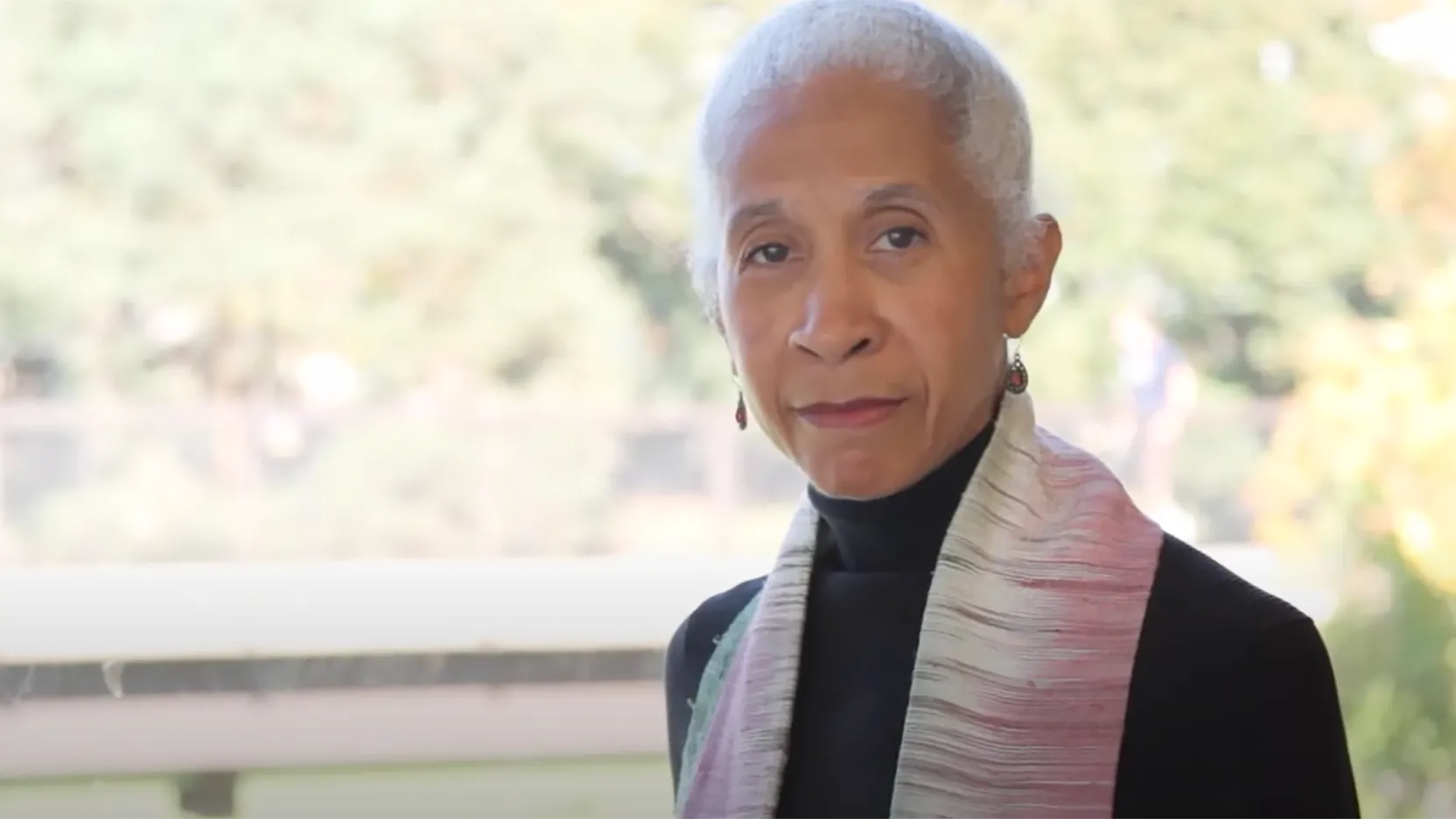

At 79, acclaimed dancer and choreographer Dianne McIntyre ’69 remains as dynamic as ever with a boundary-breaking performance set for this fall in her hometown of Cleveland.

When Dianne McIntyre ’69 takes the stage at the opening of the new Doris Duke Theatre in July, she is joined by 11 other renowned dancers and choreographers. The group is there to mark a special occasion. In 2020, a fire destroyed the original Doris Duke Theatre at Jacob’s Pillow, the famous dance institution in the Berkshires of western Massachusetts. But now, the theatre is rebuilt, and to launch its second act, these dancers—all long associated with Jacob’s Pillow—will christen the new stage with a performance.

The piece is choreographed by Annie-B Parson in collaboration with the dancers. The choreography is based on a poem/score written by Parson, the artistic director of the award-winning Big Dance Theater in New York City. As she speaks over a mic, the performers improvise on her directives. The work blurs the line between the collaborative and the individualistic. One moment, the dancers come together in a circle, their arms around each other’s shoulders. In another, they are spread across the stage, each lost in a dance of their own creation.

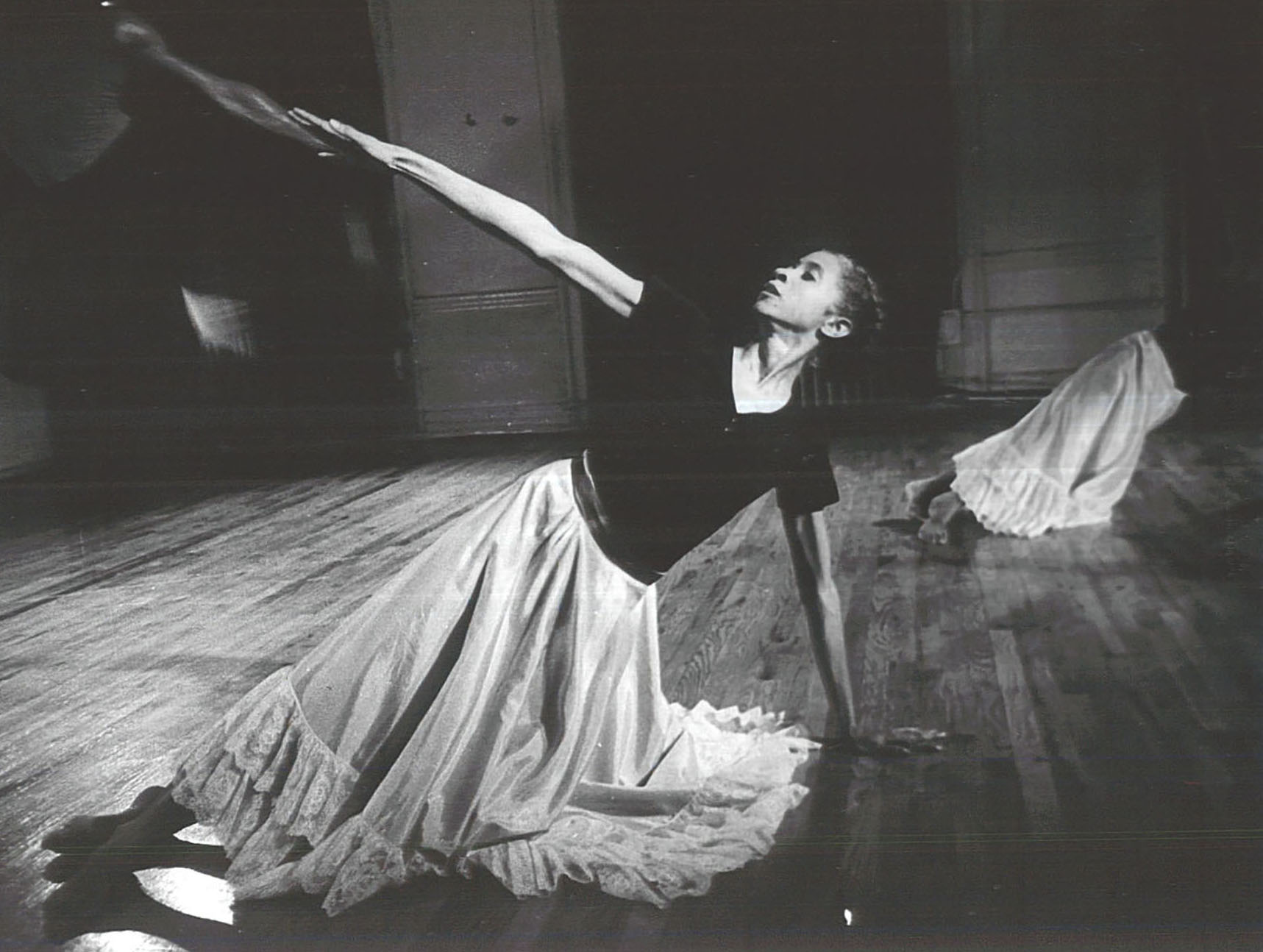

McIntyre walks across the stage, back straight. Her arms sway around her in slow, organic movements. At one point, Parson asks the dancers to stop and strike a pose. McIntyre leans back slightly, legs hip-width apart. She rests a hand under her chin and folds her other arm. She is at ease. As the piece ends, McIntyre is one of the last to leave the stage, in tow with dancer David Thomson.

It’s a fitting piece for McIntyre. With a career spanning more than five decades, she is a dance pioneer known for her creative use of improvisation and her passion for collaborating with all manner of artists, from writers to musicians to other dancers. “I wanted it to be daring,” McIntyre reflects on her career. “I didn’t want to be a copy of somebody else, and I didn’t want to be a traditionalist.”

That sense of daring is a thread throughout McIntyre’s life. From choreographing her first dance production at age 7 to becoming one of Ohio State’s first dance BFA graduates to founding the renowned company Sounds in Motion at age 25, she has always taken a bold approach to dance. That boldness is also found in the stories she chooses to choreograph—from deeply personal narratives to ambitious literary adaptations—and the boundary-breaking partnerships she’s formed.

McIntyre is known for having a unique, bold verve, but just as much for being a great collaborator. Here she works with musician Olu Dara in 1985. (Photo by Johan Elbers) In the next photo, she works with cast members from her piece “In the Same Tongue.” (Photo by Paula Lobo)

“People call her a pioneer. They have it right,” says Melanye White Dixon, Emerita Associate Professor of Dance at Ohio State. Dixon studied with McIntyre in the early 1970s in New York City. “In the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, there was not much collaboration in the traditional modern dance world,” Dixon says. “But I think she was a leader in that way, and we are collaborative now. She was the visionary.”

McIntyre is perhaps best known for integrating modern dance with music, particularly free jazz, collaborating with such legendary musicians as Max Roach and Cecil Taylor. In her wide-ranging career, she’s choreographed regional theatre productions, Broadway musicals and feature films, and won countless awards, including three Bessies, a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Distinguished Alumni Award from Ohio State’s College of Arts and Sciences, and an Emmy nomination for her choreography in the 1997 HBO movie “Miss Evers’ Boys.”

At 79, McIntyre remains a force, as evidenced by her newest work, “In the Same Tongue.” Over the course of its 80-minute runtime, five company dancers, four local guest dancers and a quartet of musicians explore the connection between their two art forms, supported by a score from composer Diedre Murray, the poetry of Obie-winning playwright Ntozake Shange and spoken word by McIntyre herself. Music, movement and words are woven together into a new kind of artistic tapestry.

In November, McIntyre will bring “In the Same Tongue” to her hometown of Cleveland. The Playhouse Square performance will mark a full-circle moment for an artist whose creativity and imagination continue to flourish deep into her remarkable career.

“Dianne McIntyre truly is an American national treasure, as an innovator and as an inspirational force,” says Philip Bither, senior curator of performing arts at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, where “In the Same Tongue” premiered in 2023.

See how McIntyre coaches dancers in this 2013 video—run time just under 5 minutes. In it, she teaches Ohio State students one of her pieces, inspired by the blues and old friends coming together again. “My teachers here at Ohio State … their belief in me gave me the courage to move forward,” she says. (Video by Elijah Palmik)

Dancing through life, and college

For McIntyre, “In the Same Tongue” is also a chance to reflect on her own relationship with music. In one of the show’s early voiceovers, McIntyre discusses how as a child, she felt “compelled to dance” whenever she heard music.

McIntyre was raised in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood on Cleveland’s East Side. (Today, she lives in the same house she grew up in.) Her parents enjoyed a range of music: big band, classical, pop. That music fostered her love of dancing. She listened to classical European music when she was little and made movements to go with it.

Her parents also inspired two of her works. In “Take-Off from a Forced Landing,” McIntyre tells the story of her mother, Dorothy Layne McIntyre, the first Black woman to earn a pilot’s license from the Civil Aeronautics Authority. In “I Could Stop on a Dime and Get Ten Cents Change,” McIntyre turns the spotlight to her father, Francis Benjamin McIntyre, a World War II veteran who spent much of his life working for the U.S. Postal Railway Mail Service.

McIntyre started taking dance lessons around age 5. She still remembers that first independent production she staged at 7. “I think we sang, we danced, and my friend Judy Fox, her older sister, who was 12, was a pianist, so she played all the music. I had live music back then, too!” she says with a laugh.

Despite her love and talent for dance, McIntyre started as a French major when she enrolled at Ohio State in 1964, with dreams of becoming a linguist/translator for the United Nations. “How I thought French was going to be so much more financially stable than dance, I don’t know,” she says.

Still, she remained fascinated with dance, taking dance major classes during her freshman and sophomore years, and performing in university concerts. The dance program was part of the Department of Physical Education then, but it was regarded as one of the finest programs in the U.S. In her junior year, McIntyre switched her major to dance, and in 1968, the university created a new degree, a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Dance, and the separate Department of Dance.

McIntyre speaks highly of the education she received, praising the intense training in dance technique and composition she underwent and the opportunities to study under guest artists and professors whom she still cites as influences, including Helen Alkire ’38, ’39 MA, ’90 HON, Vera “Vickie” Blaine ’56, ’58 MA and James Payton ’66 MA. “We got the best from our permanent faculty members and from the people they brought in for us,” she says. “We experienced the highest professionalism from those guest artists, and also from our professors, our instructors.”

Her education at Ohio State gave her the clarity and confidence to pursue a career in dance, McIntyre says. After graduating, she spent a year teaching at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee before moving to New York City. McIntyre settled in Harlem and easily fell into the city’s dance community, making friends wherever she went, going to local clubs to hear the music and taking classes at Clark Center for the Performing Arts. “I sometimes look back and think I was more bold then than I am now,” McIntyre says.

Defining dance in New York

After participating as a soloist in a new choreographers concert hosted by Clark Center, McIntyre decided to put together a company of her own. In 1972, she founded the Harlem-based dance company Sounds in Motion.

Amid all this, McIntyre found inspiration in avant-garde jazz, also known as free jazz. When a fellow dancer told her about a group of musicians who rehearsed at a day care in Brooklyn, McIntyre asked the musicians if she could attend. They said yes.

She set a challenge for herself: to move the way their instruments sounded. Looking back on that time, McIntyre says the way she danced didn’t look anything like her previous training in ballet or modern dance or West African dance. It was something new.

“I was developing a certain kind of vocabulary in my body that was the body visual version of the music,” she says. “The saxophone runs, up and down. How can my body do that? Or the drum or the trumpet or the piano. How can my body look like that sounds? That was the beginning of my education with making a body be like the music.”

McIntyre would go on to share her new skills with other dancers through her company, as well as the Sounds in Motion School, her teaching arm. One of the people she taught was Dixon, who at the time, was studying at the Dance Theatre of Harlem and had just received a scholarship to study at the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. “I was really adamant about studying with Dianne because of how she valued the connection between movement and music,” Dixon says.

Dixon describes Sounds in Motion as “a wonderful place to be” and says it was the only prominent contemporary dance school in Harlem in the ’70s. It was a place welcoming to all artists. “There were performing artists, actors, literary artists, visual artists, and we kind of converged in this cultural meeting at her studio and got to know each other and really supported each other,” Dixon says.

After 16 years of performing extensively across the United States as well as internationally, McIntyre closed Sounds in Motion in 1988 to focus on a career as an independent choreographer. Running her own company was consuming her, McIntyre says, and it required every ounce of her energy. “I wasn’t doing what I had built up the company to do,” she says. “I was using my time and money for other people to be in the studio.”

“I was developing a certain kind of vocabulary in my body that was the body visual version of the music.”

McIntyre’s star continued to rise after Sounds in Motion closed. She’s choreographed countless pieces for theatrical productions, dance companies, films and television programs, and she continued creating concert work for dancers and musicians in New York. In 2003, she returned to Cleveland to take care of her parents. The move gave McIntyre the chance to be a part of her hometown’s dance scene for the first time since she was a child. She’s worked with several Northeast Ohio companies, including Dancing Wheels, GroundWorks DanceTheater, Ohio Contemporary Ballet and Karamu House. “Cleveland really loves dance. When you go to a concert here, the dance concerts are packed,” McIntyre says. “Cleveland in general is an arts-loving community.”

In a career full of highlights, what stands out in McIntyre’s is the admiration her peers and mentees have for her. “Working with Dianne has always been rewarding,” says trumpeter Gerald Brazel, the music director of “In the Same Tongue.” “Because she put poetry, music and dance together to mold a piece into a story that has a beginning and has an end. There are people that do it, but the intensity of her work ethic and how she put the entire piece together is very unique.”

Dancer, icon, teacher

At 79, McIntyre continues to dance, although now she supplements her dance practice with floor barre and Qigong. She also starts every morning with 40 jumping jacks to “get everything going” and to help her think. And she continues to teach and mentor young dancers.

For Rhodes, the opportunity to be a part of “In the Same Tongue” and work with McIntyre is a career-defining opportunity. “She’s a walking historian,” Rhodes says. “She met Merce Cunningham, who codified the Cunningham technique. She met Alvin Ailey. It blows my mind to know that she is this sweet older woman who lives gently in Cleveland, Ohio.”

Rhodes continues: “‘In the Same Tongue’ is a piece that truly congratulates her and what she’s done. It is an honor to do this work, because I do feel like it helps me understand her, appreciate her and value her. It’s a beautiful work that celebrates who she is and why she does what she does and what moves her as a creator.”