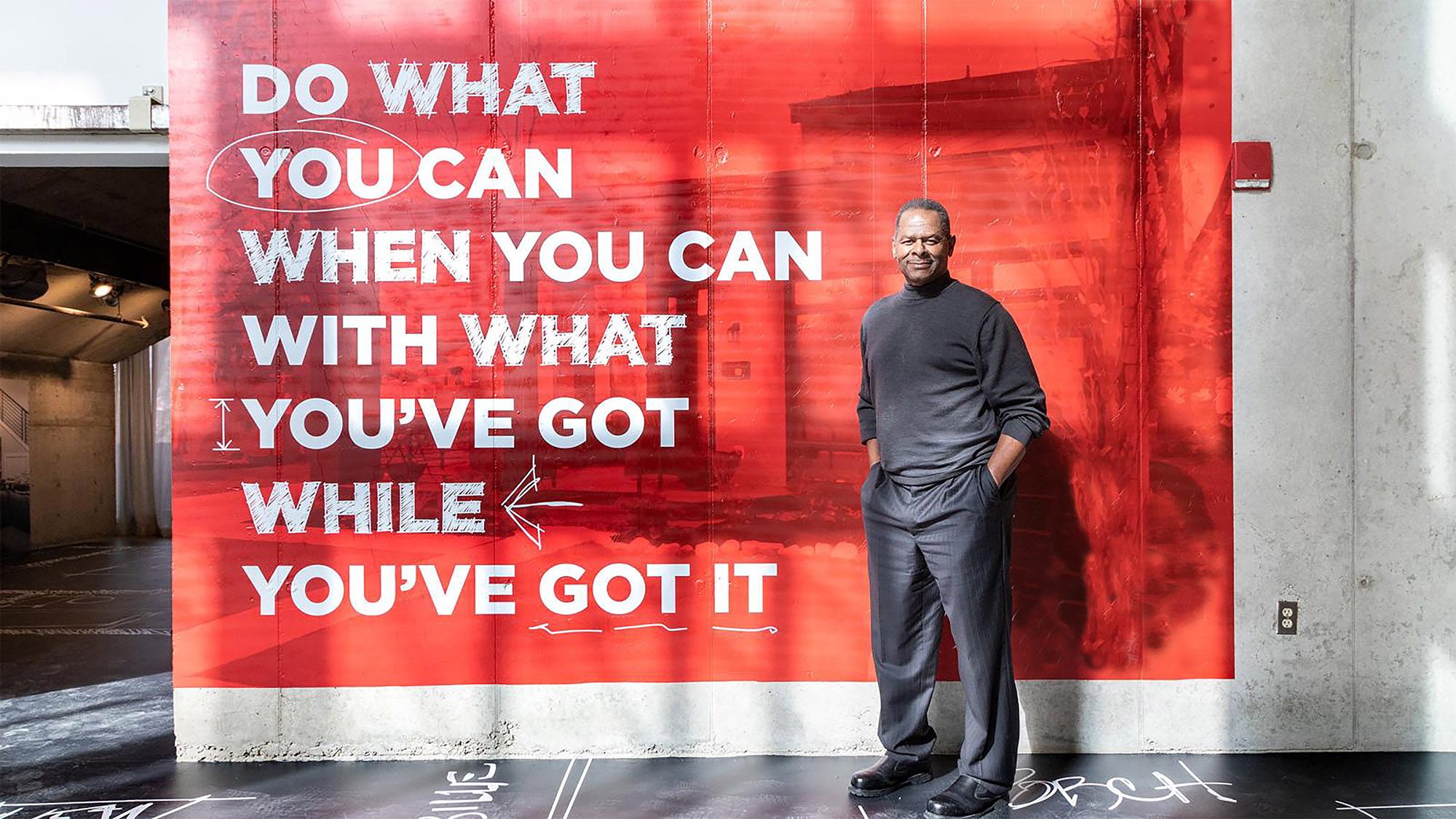

Fearless faith: How Curt Moody ’73 built his dreams

Humility and determination were a way of life for the renowned architect, who left an indelible mark on campus and beyond.

Curtis Jerome Moody ’73 was a beloved architect, entrepreneur and pitchman, known for leaving potential clients inspired, invigorated and even emotional after his presentations. He led his team at Moody Nolan, the largest Black-owned design firm in the country, with a combination of humility and determination, says his son Jonathan, who succeeded him as CEO in 2020.

“No matter what the task was, if he was called to do it, there was nothing that could keep him from it,” Jonathan says. “And he had a unique ability to call others into that same vision. I think his confidence and belief were so strong that it could get other people to say, ‘Because he believes we can do it, I believe I can do it, too.’ And if you get enough people with that kind of momentum, anything’s possible.”

Moody died at 73 on Oct. 13, following more than 40 years in a profession he said he was discouraged from pursuing because of his race. Under his leadership, Columbus-based Moody Nolan became known for its wide-ranging work, spanning sports facilities, health care, education, housing, hospitality and civic buildings. And the company designed some of Ohio State’s most prominent buildings, including the Schottenstein Center, Ohio Union and Recreation and Physical Activity Center.

Moody is celebrated by colleagues not only for his achievements in architecture, but for his collaborative approach and generosity. Former Ohio State senior vice president Jay Kasey ’11 MBOE says Moody’s sincerity during presentations always impressed him. “You got the impression that every one of Ohio State’s projects was just the thrill of his life,” says Kasey, who retired in 2024 as the leader of the Office of Administration and Planning.

He says Moody was also a skilled partner and problem-solver who never cut corners. “He was just a great leader for his firm, but for the community, too, and for the university,” Kasey says.

Moody grew up near Ohio State, in the working-class neighborhood of Weinland Park. It was a major accomplishment for him to attend the university—let alone study architecture and walk on the basketball team. “It seemed like it was so close, but so out of reach, honestly, for a Black kid in Weinland Park, whose family had never been to college,” Jonathan says.

Moody continued to outpace expectations, founding Moody and Associates in 1982 and later partnering with engineer Howard Nolan to form Moody Nolan. The company worked its way up from designing churches to taking on larger projects. Other notable builds include Columbus Metropolitan Library’s Martin Luther King Branch and Huntington Park, the home of Columbus’ minor league baseball team; Wintrust Arena in Chicago; and the Music City Center in Nashville. Forthcoming work includes the new terminal at John Glenn Columbus International Airport and the Home Court athletic facility at the Obama Presidential Center. Today, the company has 350 employees in 12 locations across the United States.

Forty-year employee Mark Bodien praises the perseverance of Moody Nolan, which won the American Institute of Architects’ highest honor, the Architecture Firm Award, in 2021. He says Moody loved proving naysayers wrong. “All these things that we had no business chasing, either because we were too small, too inexperienced or we’re a firm owned by a person of color, he would just take that as a challenge,” says Bodien, a partner and student life practice leader at the firm.

Moody was not defined by a specific architecture style, but a willingness to work with clients to bring forth their vision, Bodien says. “He would tell people in interviews, ‘We’re signature architects, but the signature is your signature, not ours,’” Bodien says.

Moody Nolan’s “diversity by design” philosophy applies not only to its dynamic portfolio, but its staff members, who come from a variety of backgrounds. The company also has supported architects of color through mentorship and partnerships, especially with historically Black colleges and universities. And the firm contributes to communities of color through building libraries, community centers, housing, schools and more.

“It was always very important to Curt that he give back where he could and that the firm do the best that we can for those underserved communities,” says 35-year employee Eileen Goodman, who serves as partner, executive VP and director of interior design.

While she remembers Moody as “an amazing visionary,” family knew him as a cherished husband, father and grandfather. Jonathan says he was an “easygoing” person who believed everything would work out. “It’s the faith that we all aspire to have,” Jonathan says. “And it’s like, ‘But it can’t be that simple.’ Well, for him, it was.”