10 of the coolest pieces in Orton museum’s collection

For the geological museum’s 150th anniversary, we photographed some of its epic evidence of epochs past—the oldest stuff at Ohio State.

This year, Orton Geological Museum celebrates 150 years of firsts and rocks, minerals and fossils that make both the curious and scientifically minded go “ooh!” Museum Director and Professor Loren Babcock—a geologist whose finds are displayed around the world—estimates more than a million specimens are in Orton’s collection. Some of the most impressive: 7,000-plus fossils that are the official examples of their species. Many are kept under lock and key. “The name-bearing specimens are the most precious we have in science,” Babcock says. “It’s incredible to handle them.” Here are 10 things that impressed us.

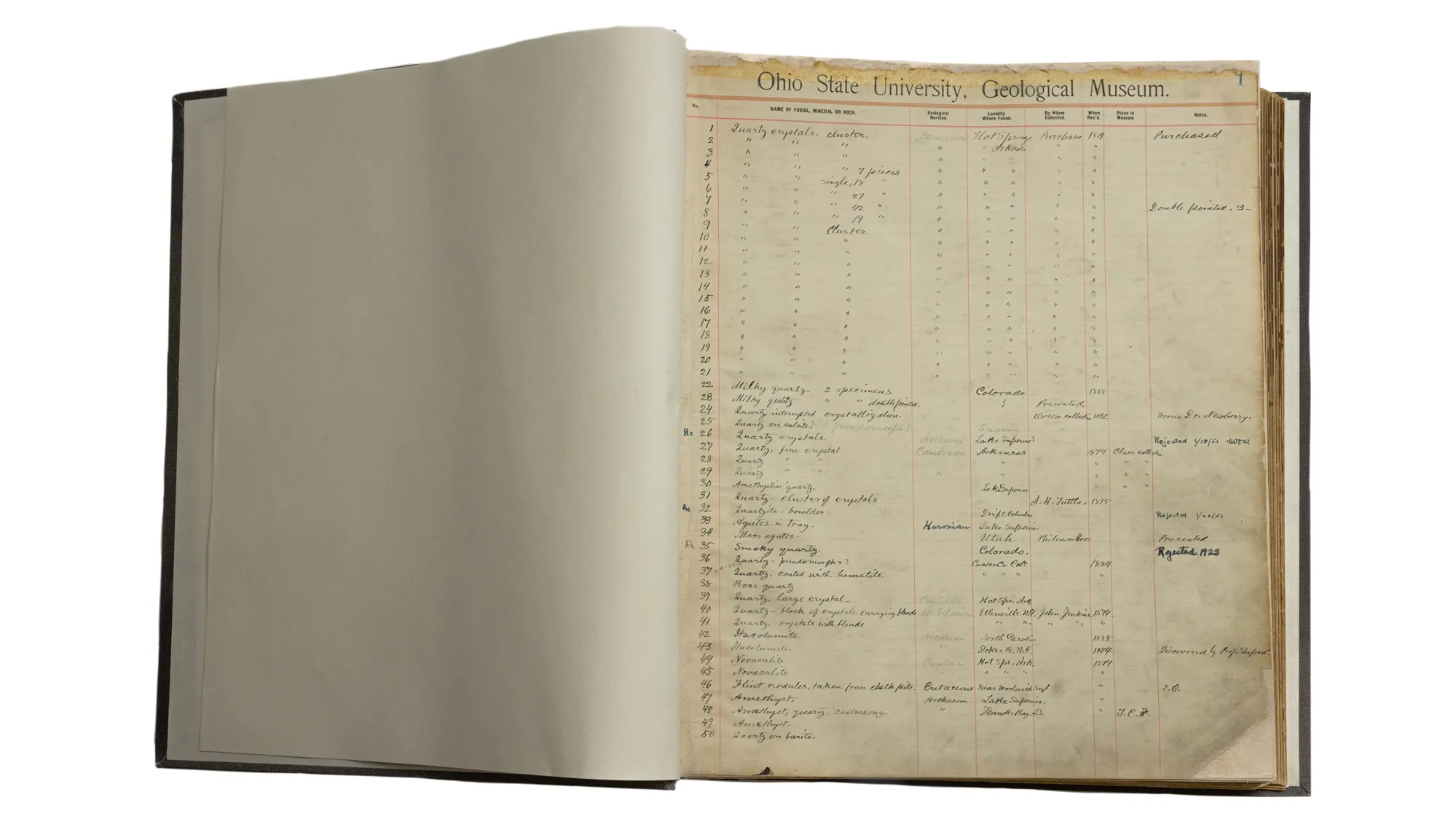

Quartz crystals

The museum’s first specimen cataloged, by Edward Orton himself, hails from Hot Springs, Arkansas. Orton was the museum’s founder as well as the university’s first president.

Megalonyx jeffersonii

The skeleton of this giant ground sloth, on display since 1896, was found that decade by ditch diggers about 70 miles from Ohio State. The discovery gave early paleontologists the best picture yet of the Ice Age mammal, first described by Thomas Jefferson about a century earlier.

Phacops rana milleri

Ohio State’s first woman geology professor, the famed Grace Anne Stewart, collected fossils of trilobites, creatures abundant in Ohio when it was covered by an ocean more than 360 million years ago. This name-bearing specimen, one of the museum’s most important, provided evidence for the theory that many species don’t evolve slowly over time, as Darwin proposed, but in rapid leaps amid long periods of stasis.

Kidney ore (hematite)

This unusually shaped mineral comes from Cleator Moor, a locale in western England rich with iron ore. Mining it was a big industry there in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Onychodus ortoni teeth

Named for Orton, this ambush-style hunter was an 8-foot-long fish with a jaw full of vicious fanglike teeth. But don’t fear, ocean-goers: It lived over 382 million years ago. This name-bearing specimen (which the star indicates) shows some of the teeth and was discovered in the 1880s just 10 miles from Ohio State.

First record book

This is one of the very few surviving pieces of Orton’s handwriting. After his eight years as university president, he continued on faculty as a geology professor and served as chief geologist of the Geological Survey of Ohio.

Mastodon jaw

These Ice Age plant-eating mammals were similarly sized to modern-day elephants. The last population before extinction is thought to have lived in the Great Lakes region.

See for yourself

Through Feb. 25, 2025, Thompson Library hosts a special collection of Orton specimens not usually on display. The museum itself is free and open year-round.

Mosasaur skull

The Tylosaurus that became this fossil lived in what’s now Kansas during the Late Cretaceous period—same as the mollusk later on this page. But this was an apex marine predator that could get 40-50 feet long and ate fish, birds, sharks and other mosasaurs.

Megaceratops jaws

When these creatures roamed North America in the middle stage of the Paleogene Period (about 24 million to 56 million years ago), they looked a lot like rhinos today but with a prong-shaped horn tipping their snout. They’re related to horses and tapirs, too.

Maorites seymourianus

The museum has one of the world’s largest collections of Antarctic rocks and fossils, and this mollusk, a cephalopod, lived about 70 million years ago. Its iridescence and fluorescence still shine.

10 bonus facts about Orton Geological Museum

Listing 10 cool artifacts at the museum leaves out a whole lot of the cool facts that Director Loren Babcock revealed about Buckeyes’ favorite fossil collection. So we created a whole other top 10 list, which includes some long-ago-made errors hiding in plain sight inside Orton Hall.

Listing 10 cool artifacts at the museum leaves out a whole lot of the cool facts that Director Loren Babcock revealed about Buckeyes’ favorite fossil collection. So we created a whole other top 10 list, which includes some long-ago-made errors hiding in plain sight inside Orton Hall.