Sympathy for the villain? Matthew Grizzard explains

In answering alumni questions, the associate professor shares why we like some bad guys and despise others — and what that means about our culture.

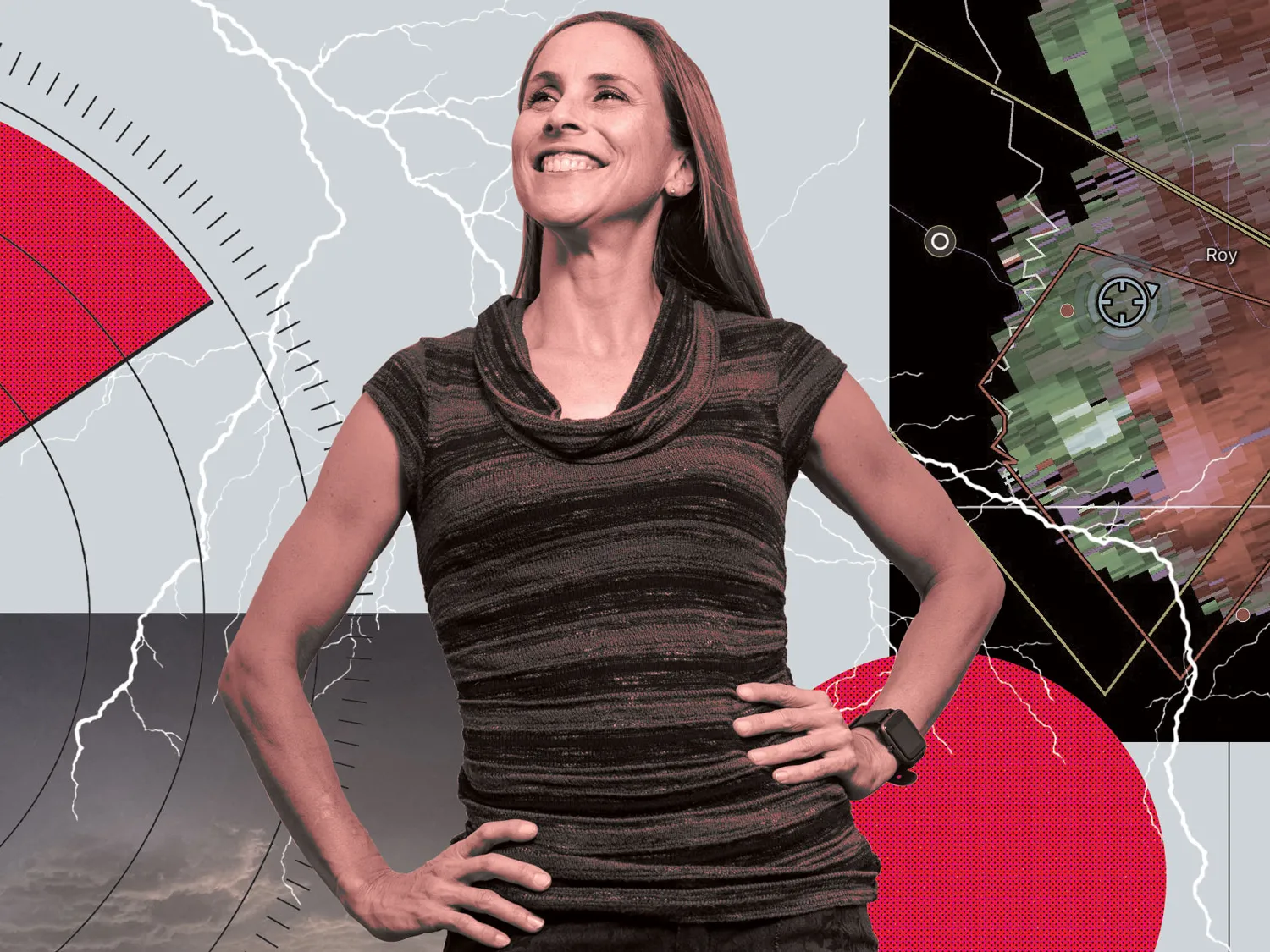

Associate Professor Matthew Grizzard’s work sits where media psychology meets mass communication. (Photo by Jodi Miller)

Who are your all-time favorite movie or TV characters? Are they heroes, antiheroes or villains? Do you know why you judge a character to be good or bad?

Often our love or hate for a character boils down to moral judgments we make against the narrative backdrop. That’s what Matthew Grizzard studies as an associate professor in Ohio State’s School of Communication. He researches popular media narratives, examining why we like stories, what makes certain characters beloved or detested, and what our perceptions say about us.

Grizzard explains more in answering these alumni questions.

-

What does it say about our character that we are drawn to antiheroes, such as Walter White, Hannibal Lecter, Michael Corleone? — Christopher Ball ’94 MS, ’98 PhD

There are several reasons why we are drawn to antiheroes and characters who are perhaps even villains (e.g., Hannibal Lecter). One reason we might pay more careful attention to these characters relates to our evolutionary heritage. We monitor the environment we’re in because we’re trying to survive, so we monitor our environment for threats. You don’t have to watch someone you trust, you have to watch someone you don’t trust, and that distrust process leads us to pay attention to these characters more than other people. We want to keep an eye on them.

When we do root for them, it’s usually because the narrative is structured so that they’re the best character we can hope for in that story. They’re the only one we can justify rooting for. So in “Breaking Bad,” people root for Walter White, but it’s because they’re not rooting for the more evil character in the show. He’s always pitted against characters far worse than him. If he were in, say, “Law & Order,” we wouldn’t root for him. Plus, he was a family man trying to earn money, so we excuse the bad behavior.

-

What do you think makes a good “evil” character? — Casey Golovko ’98

It can be really fun to root against evil characters with no good traits. Freddy Krueger was a good villain not because he was out for revenge, but because he liked killing kids. That’s just evil.

Another thing is competence. If villains are competent, intelligent, effective, that makes them a really good villain. They’re powerful and smart, so when you finally see the hero beat the villain, it’s much more satisfying. Imagine Batman fighting someone who’s stupid and clumsy. It’s not a challenge, it’s not enjoyable.

-

Why are crime dramas or true crime shows so popular? — Karen Packard ’74, ’76 MS

One reason is they paint a very reassuring view of the world. Crime dramas specifically fit what’s called a justice sequence: A crime gets committed, it gets investigated, the person gets caught, eventually the person gets put on trial and found guilty. It thus reflects our desire of what we want the world to be. Fiction can be like an ideal world for us, so seeing that justice sequence is reassuring.

With true crime, it’s keeping your eye out for the sneaky person and identifying them. There’s probably an inherent bias leading us to pay attention to those types of stories. Morbid curiosity is a driver as well. Plus, if we know how this person fell victim to this specific crime, that could make it less likely to happen to us in the future.

You also see research indicating that the people who are the most fearful of society, people and crime like those shows the most. It’s not clear if it’s causal or not, as in, “I’m afraid of crime so I watch crime,” or if it’s “I watch a lot of crime and that makes me afraid of crime.” We see a correlation there. It’s a survival instinct.

-

I am a 72-year-old grandma who hates guns, but fictional hitman John Wick resonates with me. He seems principled. How can that be? — Susan Tetley Kleiner Pidgeon ’73

He is really principled. You watch that first movie and see he doesn’t go looking for trouble, trouble finds him. He’s going after people because they killed his dog. He has a moral compass that guides him. There’s this perception that his behavior is not random, it is guided by underlying ethical decision-making, ethical rule-making — that’s one thing that makes him very likable.

Plus, Keanu Reeves looks like a nice guy, that’s why he played all those great characters in the past.

Fiction also gives us this license to enjoy things we couldn’t necessarily enjoy outside of fiction. Even though we don’t see huge differences in the judgment-making processes, you get more latitude of acceptance in fiction. I don’t think anybody would support John Wick if it was a real story. If you read about John Wick in a newspaper tomorrow, “Man goes on killing spree after Mafia killed his dog,” that wouldn’t resonate with people.

-

Why do villains with sympathetic back stories always feel like less of a threat than villains without it? i.e. Old Maleficent vs Angelina Jolie's Maleficent. – Philip LaVigne ’20

So much of our feelings toward characters are a result of moral judgments. Recent research in moral psychology suggests that moral judgments are fast, intuitive processes based in emotion and feeling. In other words, we often don’t use deliberative careful thought when making moral judgments, but instead rely on instinct and gut feelings.

Providing characters with a sympathetic backstory makes them seem like a “good person” who was forced into evil rather than someone who sought out evil for its own sake. If we believe someone is good at heart, we might excuse bad behaviors as “one-offs” or unintentional actions.

Furthermore, we are also likely to believe they might have a return to goodness in the future. That said, there are lots of reasons we might root for a character with a sympathetic backstory. For example, the “underdog effect”— rooting for someone at a competitive disadvantage — is something that is seen not only in humans but also in our closest relatives the chimpanzee and bonobo. Giving a character a sympathetic backstory often involves casting them as disadvantaged, and this could produce the underdog effect.

-

What is it that attracts audiences to a “bad guy” with an agenda?

I’m thinking of the Marvel fans who believe “Thanos had a point” in addressing overpopulation, or who rooted for Magneto because he advocated for the rights of mutants, or who love DC’s Poison Ivy because of her environmental-protection agenda. That seems different from more superficial bad-guy fandom, like rooting for the Empire because Darth Vader and the stormtroopers have cooler costumes than the Rebels. – George Carr ’94

Audience members’ responses to characters are the result of a lot of different processes and perceptions. But a character’s “agenda” — or the motivations for their actions — is an incredibly important one.

A lot of research in media psychology shows that approving of a character’s behaviors can produce what the literature calls “positive dispositions.” On the other hand, disapproving of a character’s behaviors can produce “negative dispositions.” Positive dispositions are associated with things like empathy and rooting for the character. Negative dispositions, on the other hand, are associated with things like disliking, schadenfreude and rooting against the character. The motivations a character has will likely determine whether a viewer approves of the character’s actions or disapproves.

As noted in your question, Magneto provides a great example of this type of process. Magneto may engage in behaviors that are immoral, but his reasons for doing so may be perceived as moral. These types of characters bring up age-old debates of whether the ends can justify the means. If a viewer is convinced that the reasons (and end goals) for a behavior are “justified,” then the behavior can be viewed as justified as well, even when it is harmful.

Now, imagine if Magneto was waging his campaign not because he wanted to help mutants but instead because he wanted wealth and power. The behaviors he commits and his motivations for doing them become far less justified, and I would suspect he would become less sympathetic as a “bad guy.”

-

Why is Rory Gilmore so problematic? – Maggie Sweeney ’09

I never watched the show, but evidently people dislike her a lot. I read she has an affair with a married man at two different points, so it seems like she doesn’t learn anything.

There’s this weird thing where characters we think of as problematic are not necessarily worrisome in creating antisocial effects. The Joker is a bad guy, does bad things, but gets punished. We don’t worry about him, especially for teaching kids life lessons.

What we worry about is a hero character who engages in bad behavior. Say the hero engages in a ton of violence, it almost makes it justifiable, and in the end they’re even rewarded for all the violence. That’s teaching, “You do this and under these circumstances, good things will happen.”

When I teach students about how media violence influences aggression, I’m always telling them, “It’s not Skeletor you need to worry about. It’s He-Man. If He-Man is doing bad things that seem justified, that makes it seem like those bad things are actually OK.” So Rory Gilmore could be problematic if she’s thought of as an attractive character people want to like, but then she’s doing bad things that can lead to negative influences and shifting perceptions of reality.

-

Editor’s note: After learning that a Buckeye took part on a recent season of “The Bachelor” — Alexandra Young ’11, who raised awareness about endometriosis while on the show and chose to withdraw on her own — we submitted our own question for Grizzard.

When people watch reality shows, do they perceive the people on screen as characters or real people? Do we make moral judgments about those in reality shows similarly to the judgments you’ve found people make in fictional narratives?

The question is almost like a false dichotomy; it’s assuming we perceive characters as somehow different from real people, but most of the time we’re actually perceiving characters to be very similar to real people.

We perceive real-life characters on, say, reality shows, but we’re applying the same judgments we make to fictional characters and the same judgments we make to real people so it’s almost a uniting feature.

Plus, they kind of simplify the people on those shows. They’ll do things to make them probably fit specific roles: a troublemaker, a schemer — they’ll imply certain roles and functions of the people in the overall narrative. But we’re still judging them with the same rules and moral judgment processes that we would apply to anybody else essentially.

So we do make judgments. It’s hard not to make moral judgments about people. It’s an inherent thing we do. We even apply these types of hero-and-villain identities to things that aren’t even people: animals, concepts, etc. There are even academic papers in the medical sciences describing genes as “heroes.”