Dr. Tamar Gur recently returned from a conference to a handwritten note from her children. It partially read: “We are so proud of you and your job.” The note was signed by her four children, ages 6 to 16. The job? Director of a new research program at Ohio State focused on women’s health.

The Sarah Ross Soter Women’s Health Research Program was established in 2023 through a $15 million gift from longtime supporter Sarah “Sally” Ross Soter. Her family’s philanthropic legacy includes leadership support of the Richard M. Ross Heart Hospital, which is named after her father, a 1938 graduate. “I think the program is going to be nothing short of miraculous,” says Gur, who assumed the director position in May and is also an associate professor in the College of Medicine.

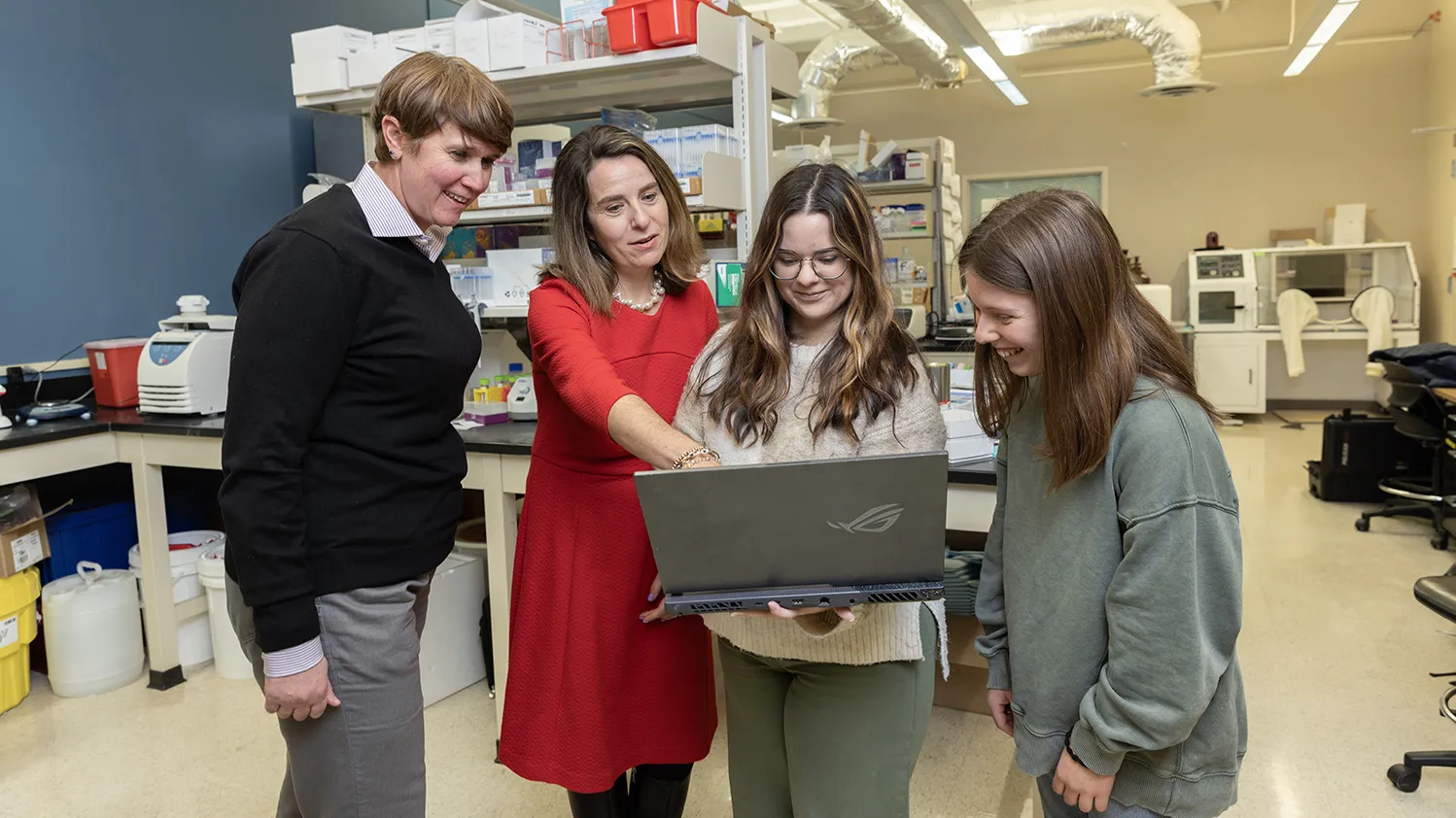

“For 50 to 60 years, research studies were all done on men and essentially ignored women,” says Kristin Stanford, a professor and researcher and a member of the program’s advisory committee.

To better understand and address women’s health care needs, additional research is essential. This includes studying how disease prevention, treatment and progression affect women specifically and differently, and ensuring their participation in studies and clinical trials throughout all stages of research, from basic to translational. “We have a lot of catching up to do,” Stanford says.

She says the underrepresentation or exclusion of women in research has significant clinical ramifications. For example, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s, osteoporosis and thyroid disease disproportionately afflict women.

Elisa Felix-Soriano, a postdoctoral fellow in Stanford’s lab, says she was shocked to find almost no research data on women while pursuing her doctorate. “It makes no sense for half of the population to be neglected. I love science, but you have to think about the people who will ultimately benefit from it,” she says.

The new program will promote and fund women-focused research through annual, competitive grant awards. Stanford says this will allow Ohio State to study every aspect of women’s health, including and beyond reproductive health. This research will eventually improve women’s health throughout their lifespan, starting in utero.

The lack of women-specific scientific data is also detrimental to the education of health care providers, which exacerbates the health gap. The new program will support rotating professorships for early-career clinicians and scientists committed to improving women’s health. Felix-Soriano thinks these opportunities are sure to attract more researchers to Ohio State.

“Had the program been in place when I was student, I would have jumped right in,” she says.

A truism of philanthropy is that it attracts further investment. This is critical in women’s health research, which is consistently underfunded. For example, analysis of award data shows that NIH funding is significantly higher for disorders that predominantly affect men than for those more common in women.

The Soter Women’s Health Research Program is already garnering national attention, giving Ohio State a competitive edge in securing additional funding. In December, a team from the U.S. Department of Defense toured the program’s laboratory “neighborhood” in the Pelotonia Research Center.

The department, which recently committed $500 million annually to fund women’s health research, was impressed by the program’s progress and the potential for future partnership opportunities.

“The new program will have immense impact on countless women,” Gur says, and this impact will extend far beyond the financial. “It will be inspirational to all of us.” She has seen this firsthand at home—her two daughters both want to pursue careers in medicine. Her oldest is interested in radiology, while her youngest “just wants to be me,” Gur says.

Her daughter isn’t alone. This year, Felix-Soriano will return to her native Spain to focus on lifestyle interventions for aging populations, extending the program’s reach internationally. She, too, looks up to Gur. “That is what I would like to be in 15 years,” she says.

Why I give: Sarah ‘Sally’ Ross Soter

I was raised to know that one should give back to the community. While I was growing up, my parents, Richard ’37 and Libby ’40, ’03 DRH Ross, always talked about the importance of helping others. They acted on this belief throughout their lives, supporting several causes, including The Ohio State University. They modeled a life of giving. I have accomplished the same with my daughter, and we are doing the same with her children.

My family’s ties with the university go back many years—both of my parents graduated from The Ohio State University. Eventually, they, my husband and I were all treated at the medical center for atrial fibrillation. We were motivated to give back by the compassionate, expert care we received. To this day, I am deeply moved when I see my father’s name on the Richard M. Ross Heart Hospital!

My first afib was at 56. From that point on, I lived in fear of another occurrence and became determined to find treatment. One doctor I saw told me I would have to “live with it.” I refused to accept this and sought another opinion from Dr. William Abraham at The Ohio State University. He listened to me and helped me find a solution for my afib.

At my first appointment with Dr Abraham, a Time magazine in the waiting room caught my eye. On the cover was a teaser for a feature on women and heart disease. The article was titled “The No. 1 Killer of Women.” It explained that research on heart conditions was mostly done on men even though these issues affected women differently. I was shocked and honestly quite angry. I knew I had to do something to help close this gap.

My afib was treated with two ablations, and I have thankfully never had another episode. Still, I wanted to help other women struggling with heart disease. I supported a faculty position—an endowed chair—that would focus specifically on women’s cardiovascular health research.

As I learned more about research in general, I realized there is a lot we don’t know about women’s health beyond cardiovascular disease. This is why I decided to make a gift to establish The Sarah Ross Soter Women’s Health Research Program. This would fund research that would benefit women everywhere. I am thrilled to be able to do this, for we cannot address these disparities in health care if we don’t invest in research focused on women.

I know I’m not alone in experiencing firsthand the gap in women’s health care. Heart disease is a condition known to affect women more often than men, but it’s certainly not the only one. It’s about time we invest in women-specific research to find the cures and treatments of tomorrow.

Illustration by Michael Hoeweler