First Black pilot at a big U.S. airline? He was a Buckeye

David E. Harris ’57 not only broke barriers, he was an all-around great guy—and credited those who came before him, like the Tuskegee Airmen.

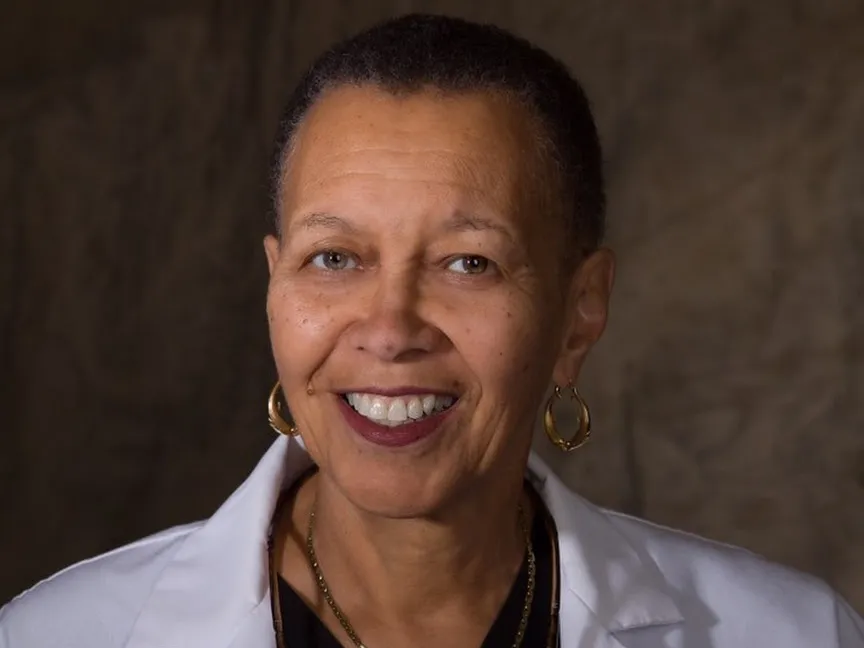

David Harris smiles from the edge of a jet engine. (Photo courtesy of Leslie Germaine and Camian Harris-Foley)

David E. Harris ’57 made history in the 1960s as the first Black pilot for a major commercial airline. To his daughters, Leslie Germaine and Camian Harris-Foley, this was just one of their father’s many accomplishments.

“When I was a kid, I thought he had superpowers,” Harris-Foley says. “He could roller-skate backwards, sew and knit, he built a swimming pool with his bare hands in our backyard, he trained our German Shepherd to understand sign language.”

Harris, 89, died on March 8, leaving behind a rich legacy as a groundbreaking pilot, as well as a mentor to numerous Black youths.

“He just loved flying and wanted the African American kids he talked to at schools to love it as much as he did and think about a career in aviation,” Germaine says. “His legacy was nurturing more Black folks into aviation.”

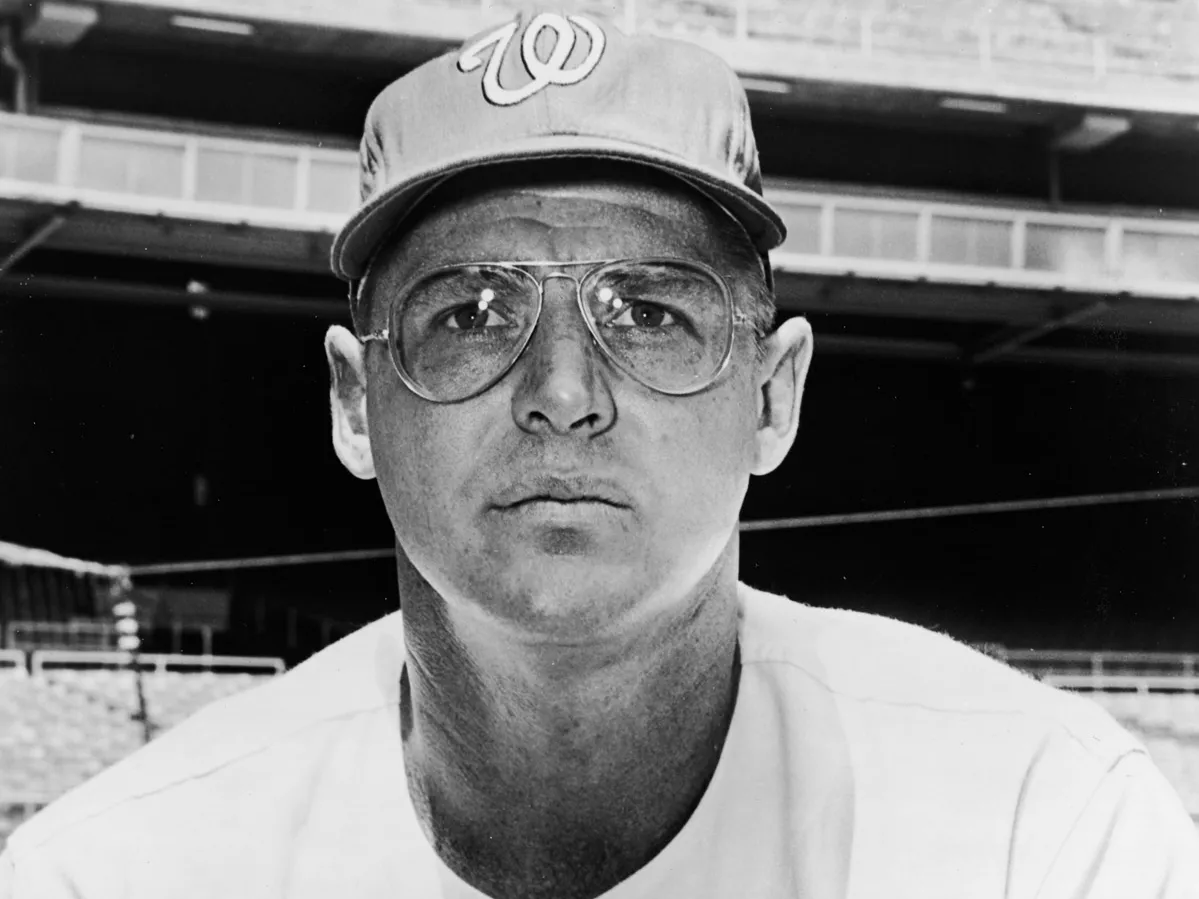

At Ohio State, Harris joined the Air Force ROTC. He tried out for the football team, didn’t make the squad, and decided to give soccer a try, even though he hadn’t played the sport in high school. “He loved playing soccer at Ohio State. He told us stories about how people would walk across their field on their way to the football games,” Germaine says. “He stayed in touch with his coach [Howard Knuttgen ’59 PhD] until he passed away.”

After graduation, Harris joined the Air Force, served on bases in the United States and England, flew B-47 and B-52 bombers and achieved the rank of captain. After leaving the military, Harris began his quest to become a commercial airline pilot. This was during the fight for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

“He had light skin and green eyes and could have passed for white,” says Michael Cottman, author of Segregated Skies: David Harris’s Trailblazing Journey to Rise Above Racial Barriers. “But he was very upfront and told the airlines he was Black.”

After being passed over by several airlines, Harris had a meeting with a representative from American Airlines who told him they didn’t care about his color. Could he fly? The answer was a definitive yes, as Harris was a talented pilot and a perfectionist who prized safety and soft landings above all else.

Because of his color, “he always felt he had to be 10 times better than the other pilots,” Cottman says. “His goal was to land and for the passengers to not feel it. His nickname was ‘Grease’ because he was so smooth landing the plane.”

Hired by American in 1964, Harris was eventually named captain. He retired in 1994, crediting the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II for laying the groundwork for his career. “He always said he stood on their shoulders,” Cottman says.

On a flight from Indianapolis, Harris noticed civil rights leader Whitney Young Jr., executive director of the Urban League, boarding and introduced himself. “[I told him] it’s because of the work that you’re doing with the Urban League that finally I’m able to secure this job,” Harris once said.

Young drowned in 1971 while swimming near Lagos, Nigeria. His widow remembered meeting Harris and requested that he pilot the special flight bringing Young’s body home. Harris’ wife, Linda, told him, as he departed to fly the charter that included Jesse Jackson and Andrew Young, “For gosh sakes don’t screw this up, you’ll wipe out the whole Civil Rights Movement.”

Harris’ quest for perfection extended beyond the cockpit. “He taught us to drive … and he would make us go through the equivalent of a flight check before we could go,” Germaine says.

His daughters say they didn’t fully realize their father’s role in history until they were adults.

“I really began to understand the importance of his place in history as an adult, when he was featured in an exhibit at a museum in Washington, D.C.,” Harris-Foley says. “To visit the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum and see photographs of our Dad was pretty profound.”