Inspiring students, saving lives, breaking barriers

One patient, one medical student, one study, one tweet at a time, Dr. Quinn Capers IV is changing the faces of future doctors and the minds of current ones — for the health of those who might otherwise be shortchanged.

By Ross Bishoff | Photos by Jo McCulty ’84, ‘94 MA

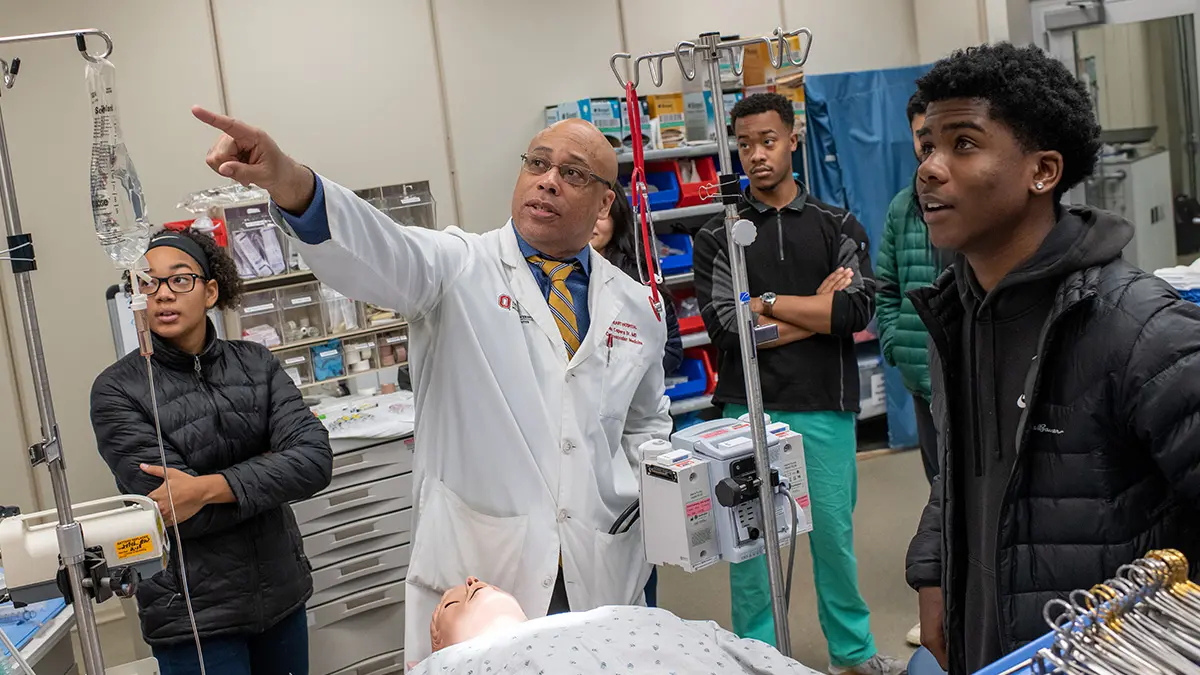

Dr. Quinn Capers demonstrates a virtual surgery suite for students from Eastmoor Academy High School. He points to a monitor that relays the vital signs to medical students studying in the lab.

He leaves his office in Meiling Hall on Ohio State’s medical campus, heading for the cardiac catheterization laboratory in the Ohio State Richard M. Ross Heart Hospital. Here, the interventional cardiologist will open a blocked artery in the heart of a patient, stopping the heart attack in its tracks. Hurrying along the west lobby hallway of Meiling Hall, Capers rushes past a familiar face. It’s his own.

Later, his patient safe and resting, Capers returns to that hallway. Portraits of College of Medicine Professors of the Year — selected by graduating classes since 1931 — have lined it for decades. The newest portrait is Capers’ own. It had been hung earlier that day.

“The patient did well, and I’m on my way back to my office when I passed the portrait again. So I had myself a moment,” says Capers, professor of internal medicine and vice dean for faculty affairs in Ohio State’s College of Medicine. “To be the first African American on that wall is very special and very humbling.”

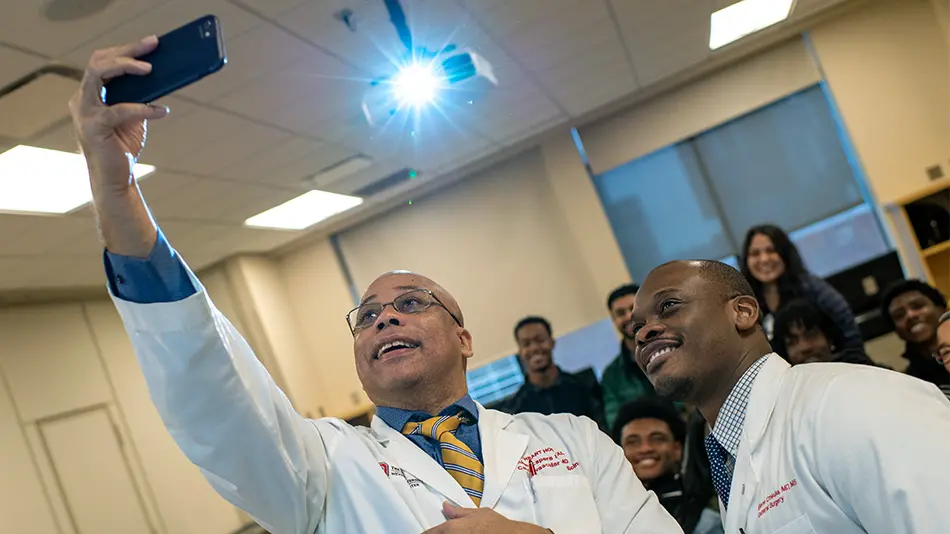

In that moment, Capers did what many of us would do. He took a selfie and posted it to Twitter. But not for bragging rights. For Capers, the post is one small step in a larger mission, the #BlackMenInMedicine campaign he and other doctors created to inspire young African American men to follow their dreams into health care, where diversity is critically scarce.

“We know there’s going to be a crisis-level shortage of black male physicians in this country, and we have data that shows it’s going to impact health care and future generations,” Capers says. “We have tried to flood social media with images of us at work in white coats or with our families at play.

“One, we want to encourage little boys or young men that they can be a doctor, too. But also, there is still an unconscious association of black men with danger, violence, negative things. Maybe it’s naïve, but we hope to play a part in changing the nation’s unconscious bias toward black men. Someday, maybe someone will see a black man and not think danger; maybe they’ll think he’s a doctor.”

Video: Hearts and minds

Because the hashtag has been used only since 2017, it’s still too early to tell whether Capers’ vision for it is becoming reality. He’s certainly had an impact close to home, though. Consider these statistics that bookend Capers’ Ohio State experience. In 1986, the year before he arrived in Columbus for medical school, Ohio State ranked 95th out of 127 medical colleges in the nation in minority enrollment, with a minority student body of 3.4%, according to the New Physicians Manual. In 2019, U.S. News & World Report ranked Ohio State second among North American medical schools for the most African American students, at 12.6%. (Neither ranking included historically black colleges and universities.) Capers, who returned to Ohio State in 2007 as an assistant professor of medicine, has been a leader in driving these changes.

In 2009, he was named associate dean of admissions and started a 10-year effort to shape the College of Medicine into a pacesetter for student body diversity. Twenty-six percent of the 2019 entering class was composed of underrepresented minority students.

Under his leadership in admissions, the college has improved on other metrics, too. Annual medical school applications increased from an average of 4,000 per year to 8,000, with the average Medical College Admission Test scores above the 90th percentile. Also, women have outnumbered men in the last six entering classes. Prior to 2014, women students had never outnumbered men in the 104-year history of the college.

“Quinn has helped create changes in our systems, the way we work, the way we think,” says Dr. K. Craig Kent, dean of Ohio State’s College of Medicine from 2016 until this past February. “Ohio State wouldn’t be where it is without him.”

Others have recognized his influence, too: Along with being named professor of the year, Capers in 2019 attained full professor status, earned the Diversity Champion Award from the alumni association and was named a master clinician by the Mazzaferri-Ellison Society, a peer-nominated honorary society at Ohio State. He also was promoted to vice dean for faculty affairs, a position from which he intends to continue to advocate for diversity.

The promotion is somewhat bittersweet — it means he’ll have one final white coat ceremony in August, when he calls out the 200 names of new medical students, welcoming them to Ohio State’s College of Medicine. “When this class graduates, that’s 2,000 doctors I helped admit, spread all over the country, working an average 30 to 40 years, treating hundreds of thousands of patients,” Capers says.

“I probably need to take another moment.”

Capers and medical students work through a question during rounds at Ross Heart Hospital.

Capers, who constantly looks for ways to be the mentor he never had, jokes with medical students.

‘An unspoken motivation’

After he greets the two students shadowing him for the day, but before bringing up Ohio State’s latest football win over Michigan, Capers streams some Miles Davis. “In this office,” he says, “we need jazz to think.”

Capers will spend the afternoon in the Ross Heart Hospital outpatient clinic seeing patients who have had chest pains, shortness of breath, wear pacemakers or carry stents in their hearts. Now, though, two people have his full attention. Dr. Eric McClendon, in his final year as an interventional cardiology fellow at Ohio State, sits across from Capers as they discuss a new patient. Spencer Ward, a first-year medical student, turns from a patient report he is writing to listen in.

Capers offers McClendon pointers on asking delicate personal questions of a patient. Later, he works with Ward on the patient report, in the process giving an on-demand lesson on why hearts enlarge, the function of each ventricle and the intended effects of different prescription drugs.

“I learn something new every day,” Ward says. “To go into a room and watch him, you see a doctor ease a patient with the sound of his voice. He shows them there is a plan. It’s masterful.”

Shadowing Capers is an invaluable experience for, well, pick your reason. He’s performed more than 4,000 coronary stent procedures. He’s a beacon of calm in the face of life-and-death heart issues. And he’s a black doctor performing at the highest level.

“Becoming a doctor is a tough road for anyone, but it seems like as an African American male, every part of the road you’re traveling, you’re trying to prove yourself,” says McClendon, who was one of two black men in his graduating class of 100 at the University of Mississippi School of Medicine. “To see someone like Dr. Capers walking these halls, there’s an unspoken motivation.”

Capers delivers a lecture on implicit bias to pharmacy students in Meiling Hall.

African American people comprise 13% of the nation’s patient population but only 4% of active physicians, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Achieving greater parity and representation will take time. While 11,861 white men and 11,595 white women applied to U.S. medical schools in 2019–20, 1,554 African American men and 2,864 African American women applied in the same application cycle, according to the AAMC.

For African American men, those numbers are actually a slight improvement in recent history. An AAMC report titled “Altering the Course, Black Males in Medicine” showed that in 2014, the number of African American men who applied to U.S. medical schools was 1,337. In 1978, it was 1,410.

It’s a report that led Capers and other African American doctors across the country to launch #BlackMenInMedicine, flooding social media with images of African American men as doctors, family men and community leaders. Their hope is to inspire young black men to become doctors.

The benefit is not only to the future doctors’ employment prospects. Research shows diversity in medicine leads to healthier patients. Black men have the lowest life expectancy of any ethnic group, at 69.1 years, compared with the national average of 78.8 years, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Yet a 2018 study from the National Bureau of Economic Research showed black men were more likely to agree to preventive measures when they were recommended by a black doctor. A separate study, published in 2008 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, found students of all backgrounds who attended diverse medical schools were better equipped to care for minority populations.

Dr. Darrell Gray II, an Ohio State associate professor in the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, also promotes #BlackMenInMedicine.

“It’s sparked a national conversation,” Gray says. “As we advance, and there are tables at which decisions are being made, it’s important to have people from diverse backgrounds at those tables to ensure their voices are represented.”

Gray also is a member of Capers’ African American Male Mentoring Roundtable, which meets to help medical students and faculty stay inspired and focused.

Capers snaps a selfie at Prior Hall with a medical student beside him and students from Eastmoor Academy High School in the background.

“I find mentoring so important because I didn’t really have that,” Capers says. He was a first-generation college student when he left his hometown of Dayton to attend Howard University, a historically black university in Washington, D.C., where his wife and oldest daughter also went to college and where his youngest daughter studies now. “In that march from kindergarten to interventional cardiology, there were a lot of forks in the road. I never had anyone to go to for advice. I try to be what I never had.”

Whether it’s providing advice or inspiration or being a role model, Capers hopes his mentorship eases the rigorous journey of students and young doctors. It’s one way to knock down barriers for his students.

Recognizing and disassembling barriers is a theme that runs through Capers’ life. It is especially on display in his fight against disparities in health care. As a mentor, professor or voice from the medical profession, it’s an issue he illuminates every opportunity he gets.

As a fellow and resident at Emory University in Atlanta, he trained at both the university hospital, which catered to wealthier patients, and the county hospital, where patients from poorer communities tended to go. The disparities he witnessed were striking. “I saw things that bothered me deeply,” says Capers, who holds lectures on health care disparities for Ohio State’s first-year medical students. “You have two groups of people with the same disease getting different levels of treatment. I made a vow to do everything I could to reduce these disparities and, at the very least, be a town crier to how unacceptable they are.”

Capers’ message is resonating. Hannah Rinehardt, a fourth-year Ohio State medical student on the admissions committee, made diversity a keystone in a recent essay for a residency application. Rinehardt is white. “The diversity of Ohio State’s College of Medicine has been a tremendous gift,” she wrote. “It’s our responsibility to understand how race and gender and trauma and violence impact our patients and ensure the next generation of medical providers learns the same.” Rinehardt is pursuing general surgery — a field historically dominated by men. She intends to channel her diverse perspective as a female physician trained at Ohio State to serve vulnerable patients.

‘He’s your biggest cheerleader’

It’s spring 2009 and Zarina Sharalaya is trying to contain herself. Standing in her parents’ living room in Cincinnati, she’s on the phone with Capers, who has just told her she’s been admitted to Ohio State’s medical school. “It was a dream moment,” says Sharalaya ’14 MD, now a cardiology fellow at Cleveland Clinic. “You’ve worked so hard, studied your butt off, done all these applications and interviews. It was amazing.”

In his time as associate dean of admissions, Capers called every admitted student to deliver the news. Most schools fire off an email. “Hearing the shrieks and tears of joy, that was one of the most fun parts of the job,” Capers says. “Last year I recorded some of the calls and shared them on Twitter. People loved that.”

The phone calls were a celebratory way Capers made Ohio State more welcoming to students. Other initiatives were more critical, especially for women and underrepresented minorities.

In 2011, Ohio State became one of the first medical colleges to adopt the AAMC’s holistic review process in admissions, allowing committees to consider a broad range of applicants’ experiences and attributes along with academic metrics. In 2012, Ohio State became the first medical school to conduct implicit bias testing and training for admissions committee members. The training allows participants to discover and overcome unconscious stereotypes. It’s now mandatory for those on the admissions committee of the College of Medicine and among senior leadership. “I’m so proud we’ve done this,” Capers says.

Also around 2013, Capers and the admissions committee noticed that, while they were getting about the same number of women applicants as men, less than half of the women accepted decided to attend. A task force found accepted female candidates ultimately found other schools more inviting.

Simple changes in the process — such as including women faculty members in the interview process — resulted in six straight classes of more women than men, from 52% to 56% of incoming classes.

Learn more about implicit bias

Ohio State’s Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity is a leader in the field of implicit bias. A four-module online training series can help you uncover your own implicit biases and what you can do about them.

Capers has tried to move the needle in his own male-dominated specialty of cardiology and subspecialty of interventional cardiology, too. Only 15% of cardiologists and 9% of interventional cardiologists are women, according to a study in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. The study showed women perceived interventional cardiology as unwelcoming to them because of the demanding work schedule and experiences with sexual harassment.

Enter #TakeAWomanToTheCathLab (search it on Twitter — you’ll see). Capers regularly invites women into the cath lab to see heart procedures. That’s how Sharalaya committed to cardiology. “After my first rotation on the acute coronary service with Dr. Capers, there was no way I was doing anything else,” says Sharalaya, who co-authored a paper with Capers on racial disparities in cardiology and starts an interventional cardiology fellowship in July. “Seeing how he connected with patients, how he was a calming presence when it’s all chaos and emergencies; it’s something I wanted to emulate.

“He says if it’s something you love, you’ll make it work,” she says. “Yes, it’s demanding, but he’s your biggest cheerleader.”

His outreach resonates with students of all ages.

Seven years ago, Capers launched a program at Columbus Eastmoor Academy High School.

Each quarter, Capers brings students from the high school’s biomedical program to Ohio State. During their visits, students — who are predominantly African American — hear presentations from medical students and experience hands-on learning in virtual labs.

“I look forward to this; it’s cool to use the skills we learn in our program and apply it here,” says Haley Warren, a junior who wants to be a pediatric surgeon. “Coming here and seeing what doctors do on a daily basis, hearing from black surgeons and doctors about their paths, it drew me in. It feels more attainable and possible for me.”

When Capers hears those remarks days later, he is speechless for a moment. Then, a smile plays at the corner of his mouth once more.

“Wow,” he says. “Yes, I’m so glad to hear that. That’s why we do it.”

A healthy ‘following’ catches on

When Quinn Capers IV ’91 MD started his Twitter account, @DrQuinnCapers4, in March 2017, it was simply to post highlights from inside Ohio State’s cardiology program. It then became his recruiting tool as associate dean of admissions.

It took on a more powerful role as he realized social media could help tackle everything from the nation’s No. 1 killer, heart disease, to the drastically low numbers of underrepresented minorities and women in the health care industry.

His favorite hashtags — #DropAndGiveMe20, #BlackMenInMedicine, #ImplicitBias and #TakeAWomanToTheCathLab — have garnered national and even international attention in promoting health and diversity.

Sister M. Xavier Schulze ’11 discovered life was more than basketball while at Ohio State. Today, she lives with total commitment — faith, love and joy in full measure.

Hear from this proud Buckeye, who has led the dance team to 13 championships, in addition to delighting fans on game sidelines.

Linda Kass ’78 MA didn’t plan to be a novelist, bookstore owner and community leader. She just followed her curiosity—and the stories that shaped her.