The vibrant world of Veterinarian Barbara Oglesbee

Macaws, mastodons and more: This 1987 alumna, teacher and animal lover specializes in exotic pets and living with intention.

Story by Jenny Applegate | Photos by Jodi Miller

Dr. Barbara Oglesbee examines a cockatiel at her practice, MedVet in Hilliard, Ohio.

Dr. Barbara Hogya Oglesbee ’87 DVM is all about grabbing life by the horns, even if that often means gently evaluating feathers. A veterinarian in Hilliard, Ohio, who specializes in birds and exotic pets, she also digs for mastodon bones, travels the country with an Airstream, and roller skates at Burning Man in Nevada. In fact, she was at the desert festival in August with her daughter, Alexandra Oglesbee Marcus ’13, when she broke her arm at a roller disco. Notice the pink cast? The parrots she treats do, too.

A different broken bone put Oglesbee on her life’s path. “I had a parrot when I was 19 or 20, and when he injured his leg, I tried finding vets around Cincinnati and that was difficult enough,” Oglesbee says. “When I finally found one who would see him, he didn’t know what kind of parrot it was or what to do for it. It just wasn’t taught in vet school. So I actually went to vet school in order to start an avian medicine program and teach it.”

She was on the College of Veterinary Medicine faculty for 15 years and continues as a senior lecturer teaching the avian and exotic companion mammal courses. But her full-time work is at MedVet in Hilliard, where she sees macaws, parakeets, cockatiels, chickens and ducks, the occasional swan or raptor, rabbits, guinea pigs, chinchillas, hedgehogs, wallabies, red kangaroos, fennec foxes… At home, she lives with her husband, Dr. Michael Oglesbee ’84 DVM, ’88 PhD, a College of Veterinary Medicine professor and director of the Infectious Diseases Institute, and three French bulldogs.

She shared a recent day with us.

7 a.m.

My mornings begin with making coffee for Mike and myself and getting breakfast for Woody, Tater and Shale. After ensuring the dogs have their medications and a chance to go outside, I head for the clinic.

8 a.m.

I use the time before my first appointment to evaluate patients transferred from our emergency service overnight and do rounds with our medical team.

8:30 a.m.

With the help of technician Aramos Ramos, I examine Cleo, a 9-year-old rabbit in for a dental procedure and X-rays. Rabbit teeth grow continuously and if not aligned, require trimming.

9 a.m.

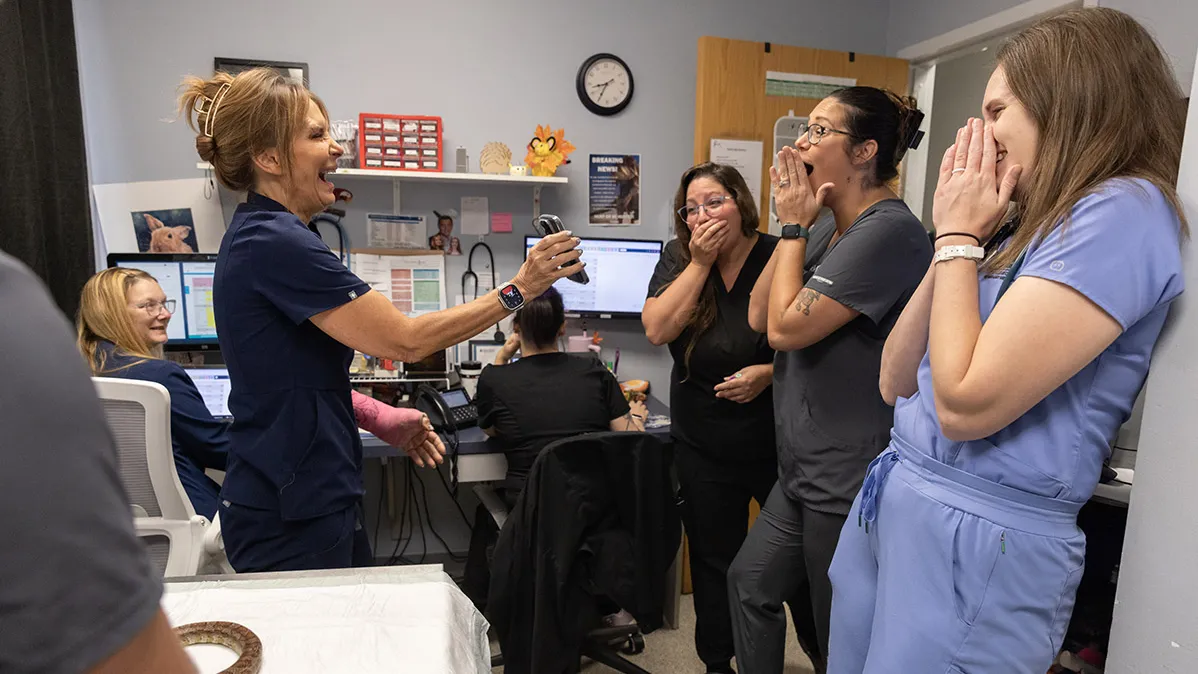

I’m sharing a humorously phone-transcribed voicemail with, from left, technicians Tonya Werner and Natalie Gillespie and Ohio State DVM student Shannon DeLeon ’19, ’21 MS. Veterinary medicine can be draining, and my mood can set the tone for my team. So no matter what challenges the day may bring, I strive to create an environment filled with hope and positivity. I want my team to feel supported, appreciated and motivated. This, I believe, impacts how they interact with clients and each other.

11 a.m.

Sammy, a blue and gold macaw, sits on my lap while I update owners on their hospitalized pets. Whenever time allows, I give hospitalized animals individual attention and affection. This benefits me as much as them.

11:30 a.m.

I talk with one of my favorite clients, who has brought her rabbit to our emergency service. After diagnostic testing, I know she is about to face some difficult decisions about her beloved pet. Although those of us in veterinary medicine came to the field for the love of animals, we are equally focused on caring for their humans. I want my clients to have all of the information they need to make decisions and to know that I am here to help them.

12:45 p.m.

Dr. Emily Fagundo ’08 DVM, head of emergency medicine, consults with me on this very cute baby ferret. We are the only emergency hospital in a four-state region that has vets with exotic animal expertise available 24/7.

1 p.m.

While evaluating radiographs from one of our hospitalized birds, I take the opportunity to teach DeLeon. We regularly have students from across the country participating in clinical rotations. I particularly love hosting Ohio State students because they have taken my elective courses and are ready for real-life interactions.

2 p.m.

Rocky, a sweet cockatiel, sits on my shoulder while I evaluate the bacterial population of his digestive tract.

3:30 p.m.

I examine Kingsley, a bearded dragon. His owners were concerned he wasn’t eating enough, but he was actually a little bit chubby! Most problems we see in reptiles are due to misinformation about husbandry. We schedule longer appointments for new reptile patients to have time to educate their owners.

5:30 p.m.

My last appointment is with a pair of bonded ferrets, Linguini and Sissy. Linguini has a seriously enlarged kidney despite no symptoms. It emphasizes the importance of annual wellness examinations.

7:30 p.m.

At home, I have dinner with Mike, then prepare tomorrow’s lecture for the exotic companion mammal course I teach at Ohio State. The primary reason I entered this profession was to educate students, veterinarians and caregivers on the treatment of unique species. To their owners, these animals are family, just as much as dogs and cats are. They deserve the same level of care.

To quell self-doubts about a new role, Wendy Pramik ’92 sought to polish her skills with a training program in Cuba.

Land-Grant Brewing founders Adam Benner and Walt Keys are Buckeye pals making a business brimming with college-like fun.

This alumna and architecture firm CEO builds up her team and other women in the industry, as well as cool structures.