Community of hope

For people who struggle to communicate, Ohio State’s Aphasia Initiative offers a lifeline. It’s all thanks to a skilled leader, generous alumni and students who care.

Sept. 10, 2022. Game day at the ’Shoe. Amber Poindexter slipped out of bed and headed to the shower. The senior operations analyst for the university’s Board of Trustees was excited to start her day. She planned to work in the board’s hospitality suite at the stadium, greeting guests, tending to their needs and cheering alongside them.

In the shower, Amber noticed something strange. She could see the water, feel the water, but she couldn’t hear it. Alarmed, she got out and shook her husband awake. She opened her mouth to speak, but no words emerged. Alvin Poindexter sat up. “Amber, what’s up?” She stared at him silently. “Are you OK?” No answer. He studied her face. She looked confused, dazed. Alvin called an ambulance.

Paramedics arrived, asking questions Amber couldn’t answer, then whisked her away to the Wexner Medical Center, where physicians determined the 45-year-old mother of two had suffered a stroke. Her husband and two sons stood by her as doctors told Amber she now had aphasia, a disorder that affects a person’s ability to speak, understand language and read and write. It is caused by brain damage resulting from a stroke, brain injury or disease.

Aphasia affects a person’s ability to communicate but not their intelligence. People know what they want to say but have trouble getting the words out. Not everyone who has a stroke or brain injury develops aphasia, but 2 million Americans have it, including actor Bruce Willis and talk show host Wendy Williams. Country music singer Randy Travis once wrote that aphasia made him feel “trapped inside the shell of my body.”

Amber felt trapped, too. She couldn’t return to the job she loved. At home in Westerville, Ohio, she grew isolated. Along with Alvin, who had to balance caregiving with his job as general sales manager for Honda in Marysville, Ohio, they struggled to find services.

Until June 5, 2023.

That’s when Amber stepped into an Ohio State classroom, the newest member of the Aphasia Initiative, a groundbreaking program providing free speech therapy to people with the brain disorder and support to their caregivers. At the same time, students who help run the program prepare for careers as health care professionals.

Amber took a seat at the table, surrounded by people with varying degrees of aphasia, from mild to severe. They ranged in age from 24 to 80 and communicated however they could—by showing photos on phones, writing or drawing pictures, using apps that talk and coaxing voices to speak again. A year later, she’s still coming to class in Pressey Hall.

“I love it,” she says. “It looks like family.”

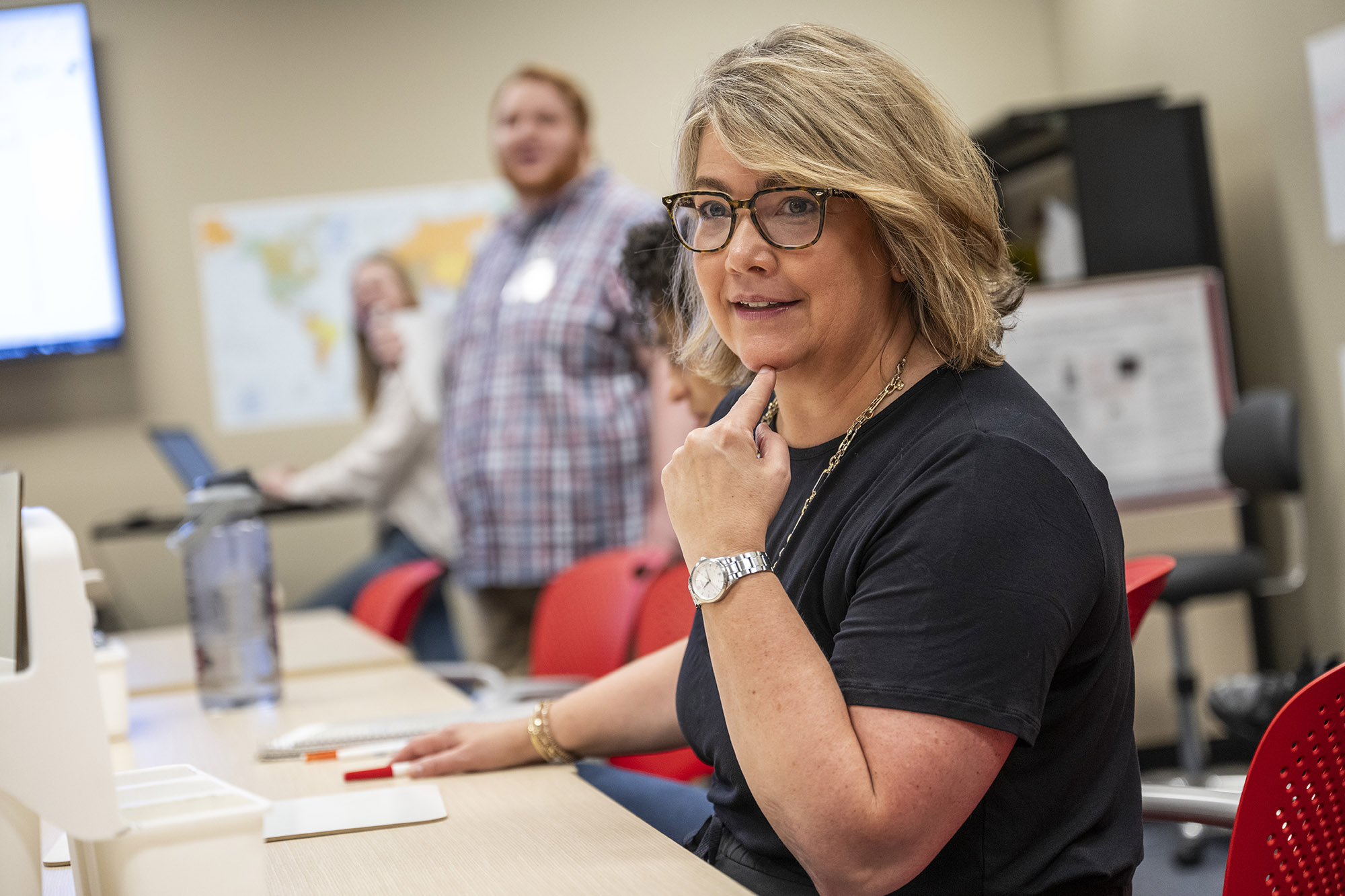

About 100 people with aphasia are active in the initiative. “We don’t call them patients because they are truly partners in the program. We learn from each other,” says Jennifer Brello, program director and clinical associate professor. Members come from all over Ohio and even out of state. They can attend in-person classes four days per week and other options by Zoom. There’s also a weekly Zoom session for caregivers.

Each year, about 150 undergraduate and graduate students participate. They facilitate the group speech therapy classes with help from two licensed speech therapists, Brello and Arin Sheeler. “The students are caring,” Amber says. “Arin and Jen are encouraging. They make us believe we can do anything.”

Students come from diverse departments, including speech and hearing science, occupational therapy, social work, medical dietetics and audiology. “The multidisciplinary approach means people with aphasia have access to more services and holistic care,” Brello says.

Students say they benefit, too. “We get so much exposure to interprofessional communication,” says Grace Wallace ’24, who majored in speech and hearing science. “It’s like working with a medical team, which is what we’re going to be doing when we’re out on the job.”

The initiative is unique. “Other universities have aphasia programs, but few if any of them draw students from multiple disciplines,” Brello says. “We created that here at Ohio State. When I speak at conferences, people ask me, ‘How did you do it?’”

It was a team effort, but the idea came from a pair of Ohio State alumni.

For years, Central Ohio resident Richard Foster ’65 had been looking for a way to help people with aphasia and their families. He had personal experience: In 2006, his wife, Louesa Callahan Foster ’65, experienced a stroke and lost most of her ability to speak and write.

Louesa was devastated. She’d led the Upper Arlington Education Foundation for 15 years and had a busy social life. Her family struggled, as well. “You’re totally unprepared, and you have no idea what the best way to deal with it is,” Richard says. Their children, Ted and Kiley, provided support, but many friends drifted away because aphasia makes communication so difficult. “It’s lonesome, very lonesome,” Richard says.

At first, the Fosters focused on finding intensive speech therapy for Louesa. They traveled to several out-of-state facilities, including the Adler Aphasia Center in New Jersey, a bustling place offering services to people with aphasia and their caregivers. But after a few weeks, the Fosters wanted to return home.

Columbus had no similar hub. There were private speech therapists, of course, and the Fosters could afford therapy. But they knew many people struggled to pay for services, especially because insurance coverage is limited. And where could caregivers go? There was nowhere. They began to wonder: What if such a place could be created in Ohio? And what if it could offer free services, connect caregivers to help, and deploy Ohio State students to provide therapy while training them for professions?

In 2012, the Fosters found their ideal partner when Richard contacted Brello, who had just transitioned into teaching after 11 years at the Wexner Medical Center. There, she had honed her clinical expertise and methodology while providing speech therapy to patients with brain injuries.

“I like to reimagine the way we typically do things,” she says. “I like to break ‘the rules.’” She understood the potential that Richard described and started envisioning the program by asking herself, “How would I want someone to care for me or a family member?” Her answer: “I’d want the best care possible.”

Three years after Richard’s first email, with a generous grant from the Foster family, Ohio State launched the Aphasia Initiative within the university’s Department of Speech and Hearing Science. Nine years later, the initiative is “blossoming and growing,” Brello says. There’s a second location at Ohio State Outpatient Care East in Columbus. The team is also training students at several Ohio universities and collaborating with a North Carolina aphasia group run by Sevanne Poirier Epperson ’95 MA. Brello and the Fosters plan to expand the program to Ohio State regional campuses, starting with Lima.

The Fosters’ son, Ted, jokes, “If Jen wants to take the program to Mars, we’ll probably support that.”

If you think Brello and the Fosters had a master plan from the start, you’d be wrong. “We started with just graduate students from Speech and Hearing Science, but the program grew organically as we responded to the needs of our members,” Brello says.

She drew in social work students to offer case management services, such as helping members get their medications. Next came occupational therapy students to teach fall prevention classes and medical dietetics students teaching nutrition and more.

Social worker Kathy McFall ’22 MSW says her internship with the initiative prepared her for her job as a discharge planner at OhioHealth Grant Medical Center in Columbus. “Shortly after I graduated, I met with a patient who’d had a stroke,” she says. “I knew better how to communicate with her after working with the Aphasia Initiative. I asked her yes and no questions, and I gave her choices. After our meeting, her husband said, ‘Thank you for taking the time and being so patient with her while she expressed what she needed.’”

Ohio State’s Aphasia Initiative

The Aphasia Initiative offers engaging and enriching activities to help people living with the brain disorder improve communication skills.

The initiative has spring, summer and fall sessions. Students teach classes in verb-focused word finding, conversational skills and how to use technology as an aid. The room has fluorescent lights, a few computers, a whiteboard and wooden tables. If that seems drab, the vibe inside is anything but. The space brims with laughter and energy, and the door is always open.

“Members can come for as long as they want,” Brello says. “It’s their community. They make friends here. We have one member who’s been with us since we started.”

That is 69-year-old Frank DeVito, who always finds a way to get to class. One recent morning, he tripped and fell while getting ready. His right arm is paralyzed from his stroke, and his wife couldn’t help, so DeVito called 911. After paramedics righted him, he made it to class, where he regaled his friends with his story.

His friend circle includes Gabby Rosenthal ’22, ’24 MA, who met DeVito in class. A speech language pathology major who played on Ohio State’s hockey team, she and DeVito bonded over a love for the sport and joking around. “We’re like two peas in a pod,” says DeVito, who attended many of her games.

“Frank has been more than a friend,” Rosenthal says. “He’s been a mentor, teaching me invaluable lessons in resilience, patience and the power of maintaining a positive mindset.”

DeVito wants the public to know one thing: People with aphasia have the potential to improve over the years. When he had his stroke in 2013, doctors told him he’d recover any skills he could in the first year, then nothing. “They were wrong,” he says. “I’ve been coming to speech therapy for 10 years. Look at me now!”

Brello says that’s one of the biggest lessons she’s learned through the initiative. “There’s evidence of continual recovery. We’re not finding a cap.”

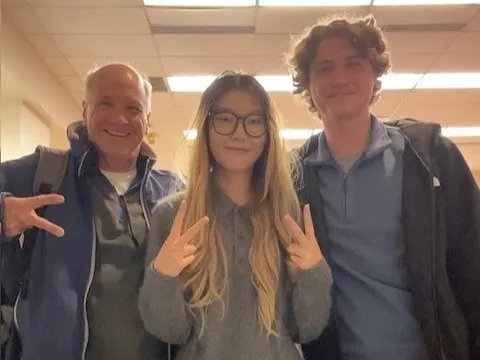

Frank DeVito has been joining classes since the start nine years ago and proves that continual skills recovery is possible. Previously, experts believed progress could be made only for a year after the stroke or injury. At left is Vince Lemle.

That eye-opening finding speaks to another high-impact opportunity created by the initiative: learnings that can help craft more effective therapy. Professor Stacy Harnish ’00 knows this well. She directs the Aphasia Laboratory at Ohio State, which she founded three years before the initiative’s start to research ways to maximize the benefits of therapy. Brello is a member of Harnish’s lab team, which also includes professional speech language pathologists and graduate students.

The laboratory is conducting multiple studies, such as one funded by the National Institutes of Health to investigate how therapy can be personalized based on a person’s genetics, cognitive skills and brain structure. “We’re presenting our work at conferences nationally and internationally; our publications are cited all over the world,” Harnish says. “What we are doing here every day at Ohio State is benefiting not just the local community. It is contributing to our collective knowledge about how to assess and treat aphasia, how to educate the community and how to change our systems to make them more accessible to people with language disorders.”

Members of the initiative often participate in her lab’s studies (as do other people living with aphasia who are not part of the Ohio State program). The level of access is incredibly valuable for research purposes and the close relationship pays off: Members provide feedback about her students’ work and approaches, Harnish says. Members benefit, too, as PhD students present special aphasia-friendly sessions sharing their findings. Recent topics have included teletherapy, brain cue strategies and the benefits of self-efficacy.

Harnish works closely with her graduate students to design and implement their research projects. One example is PhD candidate Courtney Jewell ’23 MA, who is investigating sources of stress for people with aphasia and what helps them. “We’ve found that people with a low sense of social support, who don’t feel like they have anyone to reach out to, have the most symptoms of anxiety and depression,” Jewell says. “They have the most difficult time adapting to aphasia, no matter how long it’s been.”

People are taking notice of the all-around benefits of the setup at Ohio State. The integration of research and clinical practice serves as a valuable model, says Matthew Cohen, associate professor at the University of Delaware, who visited Columbus to interview initiative members, caregivers and staff as part of a collaborative research study. “It was a pleasure to partner with such a productive and fun group of people.”

Fun is right. There’s an air of theatre to many of the classes, especially when the leader is speech therapist Sheeler, who serves as the clinical supervisor. She glides across the room, hands in motion, dipping down so she can be on the same level as a seated member, then springing back to the front of the room, where she points to an image on the screen. “I’ve always been an animated talker,” she says. “I know this way of communicating is very helpful in supporting our members’ language and understanding.”

It’s entertaining, too. In a recent class, Amber Poindexter grins when Sheeler uses the word “cat” and then hisses. Amber has made great strides since her stroke, when in the days after, she could say only one word: “Why?”

But since joining the initiative, Amber’s vocabulary and fluency have vastly improved. She’s an eager participant in the classroom, answering some questions directly, but she’s most comfortable writing down her answers then reading the words aloud.

Her family has noticed positive changes. Husband Alvin says she is braver, no longer afraid to speak to others and ask questions. “It’s inspiring to me and the boys,” he says.

Their sons, both Ohio State students, are Miles, a third-year, and Malcolm, who just started his first year. They say they’re grateful their mother has new speech techniques to use and new friends. The family also values the resources for caregivers.

Without the Aphasia Initiative, Amber says she’d feel “unfulfilled—like I didn’t have a purpose.”

But now? Amber says, “I have blessings and miracles. I’m here. I’m happy.”

The Ohio State Aphasia Laboratory

The Aphasia Laboratory researches ways to maximize the benefits of therapy and treat language and cognitive impairment in people with aphasia.