Built for the future

Ohio State’s engineering technology program is designed to create the next generation of manufacturing engineers who will push the state’s top industry into an age of automation and global competition. See how Zachary Ernest ’22, ’24 is fulfilling that promise.

“Ohio State became a pathway for me,” Ernest says. “When I was 18, I never even had a passing thought that I could become an engineer. But perseverance makes you something you never thought you could be.”

For a nontraditional, first-generation graduate who spent most of his 20s feeling directionless, Ernest’s perseverance, buoyed by support from his family and his newfound Ohio State community, became a life preserver.

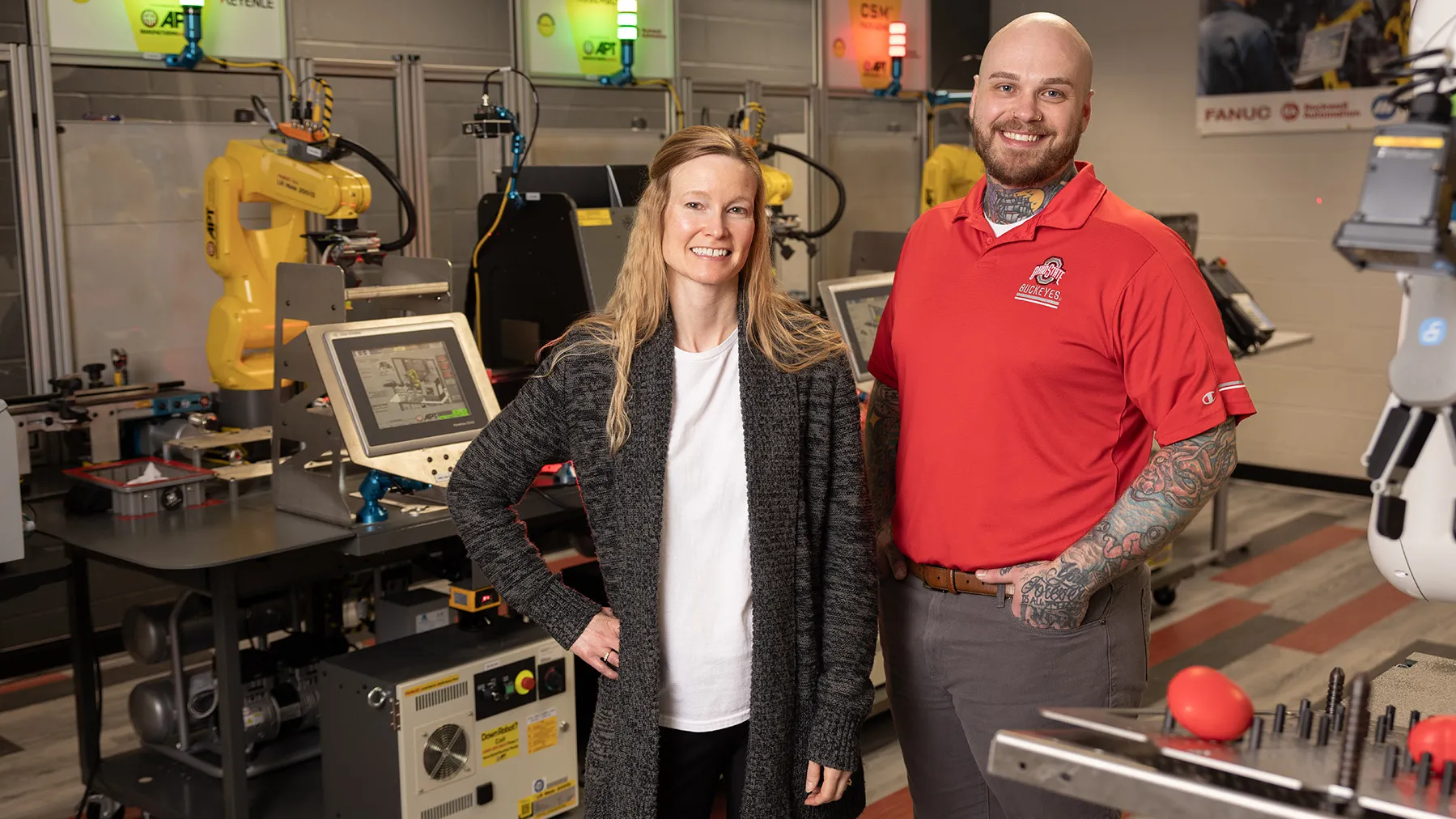

Assistant Professor Amber Rader has been a teacher, an inspiration and a support for Ernest. They pose in a tech lab on the Mansfield campus, where Ernest earned his degrees.

Surviving tragedy, with help

Amber Rader ’98, ’99 MS is a program coordinator and assistant professor within Mansfield’s engineering technology program. One night in January 2023, she got an email from Ernest asking her to call him as soon as possible. When she did, she was mostly speaking to Ernest’s father, Ron, because Zack was too distraught.

Earlier that night, Ernest had found out his best friend, housemate and brother-in-law Malcolm Jenkins had died by suicide. In the thick of his grief, Ernest was concerned about classwork. But the truth was Rader had become a rock of support. “I felt so bad for him; he was really suffering,” Rader says. “I’m definitely not a counselor. All I did was try to support him.”

That was a theme in their relationship.

Along with the tragedy of Malcolm’s passing, which happened during Ernest’s junior year, he also worked 50 hours a week as a student and struggled with some classes, often spending time in Rader’s office trying to understand coursework. Then, his senior year, about a year after Malcolm died, Ernest underwent a massive back surgery during his yearlong capstone project.

Along with his family, he says, it was often his classmates and Rader who picked him up when he needed it. “She genuinely cares,” he says, tears welling.

“She was compassionate when I needed it, but there were times she was hard on me, and I needed that too. It’s stuck with me. It’s a unique combination, but one I want to live up to for those around me.”

Rader says the small classes grow close through the four-year program, professors included. “A lot of these students just need somebody to believe in them—that’s easy to do when you work with them every day,” she says. “Zack had to overcome a lot, but I knew he could do it. I knew he could be successful.”

Following his brother-in-law’s death, Ernest considered dropping out. One reason why was because it brought his own mental health fight roaring back. During his 20s, Ernest battled severe depression, due in part to an engagement breakup, but also due to feeling stuck in life.

“He struggled with his purpose,” says Kristine Jenkins, Ernest’s sister and Malcolm’s widow. “There were times he was just a shell of himself.”

That came to a head one afternoon when he was 23. A disturbing phone call to his mother, Denise Wiley, resulted in her and Kristine picking Ernest up from work and driving him to a mental health facility where he checked in for a week to get help.

“He didn’t fight us,” Kristine says. “He knew it’d suck, but he knew it was time.”

After that stay, Ernest began searching for that new path. What he found was an identity.

These engineers will power Ohio

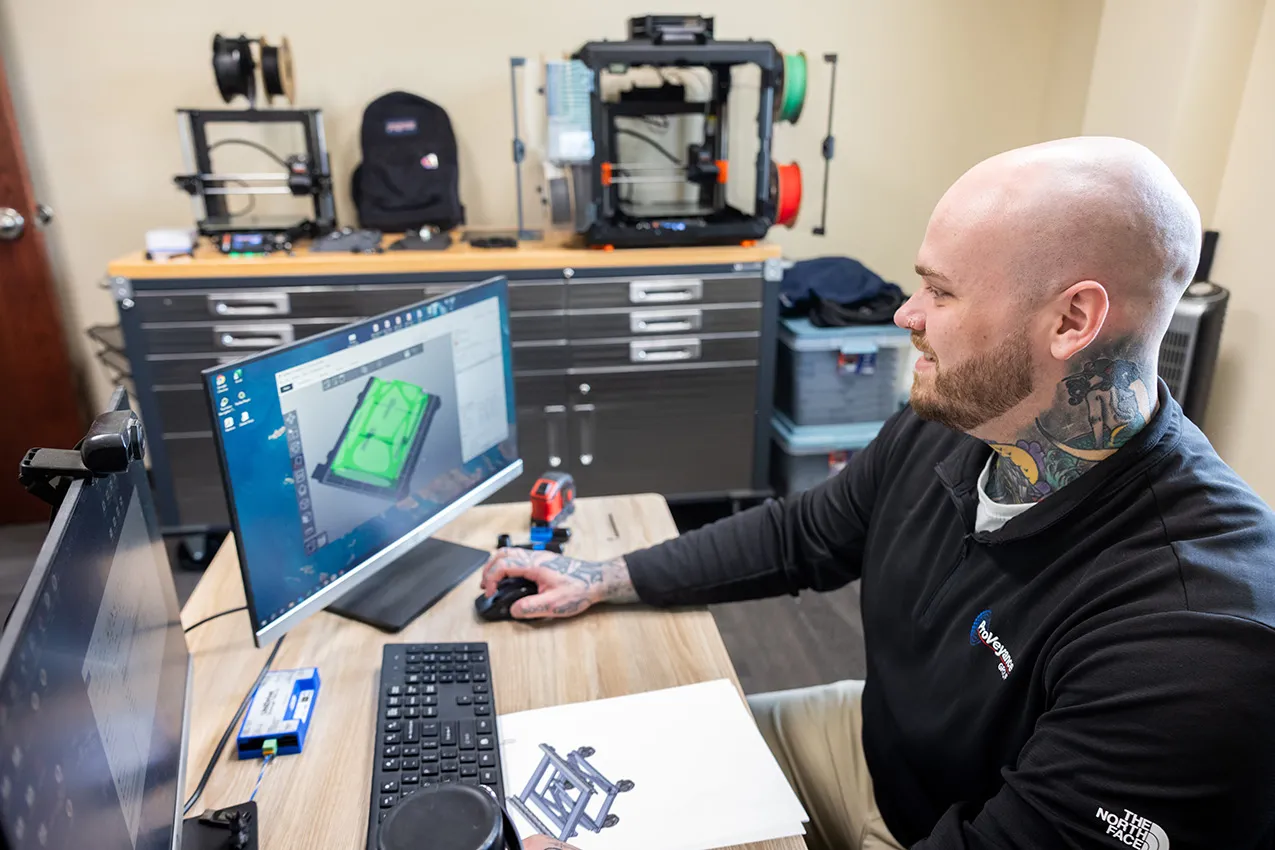

Within a lab at Ohio State Mansfield, surrounded by robotic arms and controllers—the automation used in high-tech factories—Ernest is right at home. He’ll lead visitors around the equipment, demonstrate it and talk up the engineering technology program.

Turns out, he shines at this. It’s why he’s often asked to return to campus to talk to incoming freshmen or visitors, such as representatives from the University of Tennessee or then-Lt. Gov. Jon Husted, now a U.S. senator.

During one of those demonstrations, Kristine and Wiley attended to watch him do his thing. “Mom was so emotional—so was I,” Kristine says. “I was like, ‘That’s my baby brother.’ Everything he’s overcome, it brings tears to my eyes. This degree, this new job, it’s made him so much more confident. Seeing the man he’s become, we’re so proud of him.”

Being an ambassador for the program is important to Ernest because he’s not only an example of what the degree can do for one graduate’s career, but because he believes in its potential to produce engineers who can vault manufacturing into the automation era.

“When I really need to influence people, I call Zack,” Rader says. “He could sell a ketchup popsicle to a woman wearing white gloves.”

More important, Rader says, he sees the big picture: Manufacturing is evolving. In Ohio, that’s critical to understand. Manufacturing is the state’s top industry, contributing over $133 billion to Ohio’s gross domestic product in 2023, according to the Ohio Manufacturers’ Association. It’s a sector that employs over 687,000 employees in factories that make everything from auto engines to macaroni to baby bottle nipples.

But there’s a problem. Not all manufacturers are adapting to Industry 4.0, or the fourth industrial revolution, in which dirty, hot factories with armies of employees working on individual machines and assembly lines evolve into clean, efficient warehouses of automation with smart production lines and robotics taking over repetitive tasks factories can no longer find employees to do.

“The factory has changed,” says Pat Cucco, process and product engineer at Ashland Conveyor and Ernest’s boss. “Our engineers need to be quick thinkers who can solve problems and adjust to the challenges we face on the shop floor. They not only need to understand modern technology and processes but also how to bring those innovations into our facility quickly and smoothly.

“If you can have a lights-out factory where you run it with an app on your phone, that’s probably going to happen at some point.”

Ohio State worked directly with industry professionals to create the engineering technology program and continues to do so. Beginning this fall, Leslie Weist Brenner ’13, vice president of operations at Michael Byrne Manufacturing in Mansfield, will become the chair of the program’s Industry Advisory Council. Industry pros like Brenner guide the program but also offer students mentorship, facility tours, internships and even careers upon graduation.

“I truly believe in the program because I see the quality of graduates it’s producing,” she says. “Automation is becoming so important, and we need people who understand that language, speak it, make it work.

“But especially as Ohio puts a big focus on bringing back manufacturing and promoting it here, we need leaders. That’s what this program really creates, those leaders.”

Brenner says Ernest is a perfect example of what the program is all about, creating well-rounded engineers who are also adept in business practices and leadership skills.

“Manufacturing is about solving problems,” Ernest says. “This program is so robust. It creates an engineer who brings many skills to the table to solve problems. Really, that’s what we are. We’re problem-solvers to the highest degree, and that’s what this industry needs.”

Since his brother-in-law’s death, Ernest and his sister, Kristine Jenkins, have remained best friends and housemates.

Malcolm would be proud

Ernest looks like someone you’d find in a heavy metal mosh pit on a Friday night. His massive frame and shaved head, his beard and $15,000 worth of tattoos inked on his body. Only you won’t. “On a Friday night?” He smiles. “I may go to Meijer.”

He spends his time at work, the gym or home, where his true love is his 7-year-old goldendoodle, Andy—named after Andy Bernard from “The Office.” His hobby? “Has he told you he bakes?” his boss Cucco asks, letting that hang in the air. At the factory, his pumpkin doughnuts and cupcakes don’t last long in the breakroom.

“They’re so good,” says Kristine, who lives with Ernest at their home in Galion. “It’s weird. Here’s this big, beefy dude who wants to bake a cake. He’s got layers. Like Shrek, he seems like this big, intimidating guy, but he’s a teddy bear.”

Kristine and Ernest are best friends within a large, extended family in which he is the baby and the first to graduate with a college degree, earning his diploma on an emotional graduation day.

“It was surreal,” he says. “I remember Kristine tying my tie because I had no idea how to do it. I remember saying, ‘I wish Malcolm was here.’ We just cried. When I started school, working full-time, I never thought I’d see the light at the end of the tunnel. Then I did and it seemed to go by in the blink of an eye.”

It was a rigorous journey and Malcolm was one reason Ernest went to college, often keeping him motivated during long days and late nights. After his death, Kristine made sure her brother got that diploma. “He and Malcolm talked about it all the time. I just reminded him of that, how Malcolm wouldn’t want him to quit,” she says.

Not only did he stay in school, Ernest remained after graduation near his hometown in north-central Ohio with his job in Ashland and his home in Galion.

It turns out, that’s common among engineering technology graduates. Of the two graduating classes so far, totaling 29 combined in 2024 and ’25, all the grads from the Mansfield and Lima campuses have found jobs within their regions, and at least half from Marion have done the same. Newark’s program began in 2023.

Like Ernest, many engineering technology students want to get a degree close to home at regional campuses, in smaller towns surrounded by industry. That means after graduation they have the benefit of finding good-paying jobs—making average base salaries of $80,000–$87,000—where they grew up.

“There’s a lot of towns in Ohio that are going to benefit from this program, and it’s going to make Ohio a more desirable place to live,” says Rader, who grew up close to Mansfield, left for an industry job in another state but returned and eventually started teaching at Ohio State Mansfield. “That’s important to me. It’s a reason I believe in this program.”

Ernest considered leaving Ohio after graduation. Then he thought, why? This is where he endured the long hours and late nights, the tragedy and triumph. This is where his family lives, where his support remains.

To Ernest, “This is home.”